by Steve Laug

This particular Peterson’s sandblast pipe was purchased on 01/20/2026 from a Facebook seller in Quaker Town, Pennsylvania, USA. It really is another beautiful smaller Bent Billiard with a gentle curve to the shank and stem. The bowl is sandblasted and stained with a contrast of browns. It is stamped on a smooth panel on the underside of the shank and reads Peterson’s [over] Irish Whiskey [over] the shape number 338 [over] Made in the [over] Republic [over] of Ireland. The bowl had a thick cake and an overflow of thick lava in the sandblast rim top and inner edge of the bowl. There was grime ground into the finish and dust and debris the sandblast. There was a triple ring band on the shank – two brass sandwich a flat yellow band. The vulcanite bent taper stem has the gold “P” logo on the left side. It was oxidized, calcified and had light tooth marks and chatter on both sides of the stem ahead of the button. Jeff took photos of the pipe before he started his work on it.

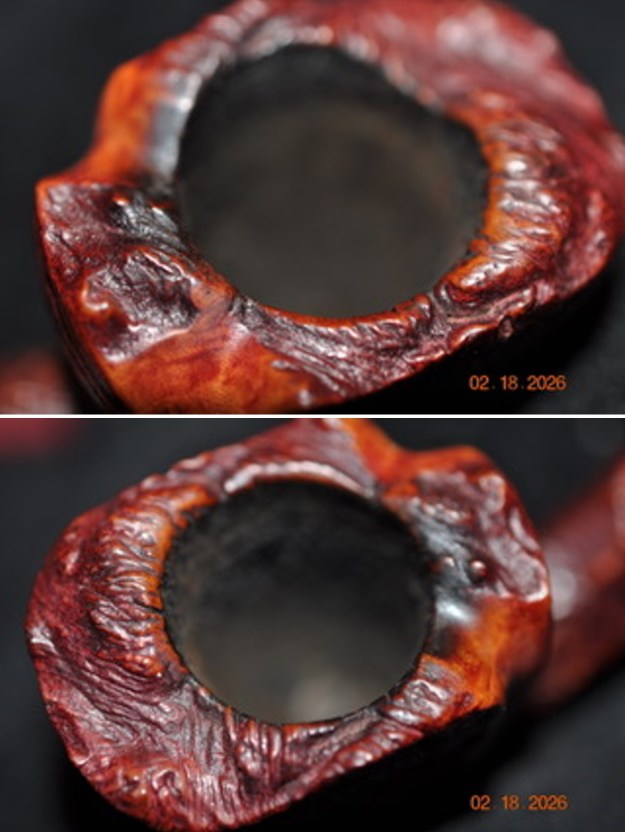

Jeff took photos of the bowl, rim top and the stem to show the condition of the pipe when we received it. You can see the thick cake in the bowl and the thick lava on the sandblast rim top and inner edge. He also captured the condition of the stem showing the oxidation, calcification and tooth chatter and oxidation on the top and underside ahead of the button.

Jeff took photos of the bowl, rim top and the stem to show the condition of the pipe when we received it. You can see the thick cake in the bowl and the thick lava on the sandblast rim top and inner edge. He also captured the condition of the stem showing the oxidation, calcification and tooth chatter and oxidation on the top and underside ahead of the button.

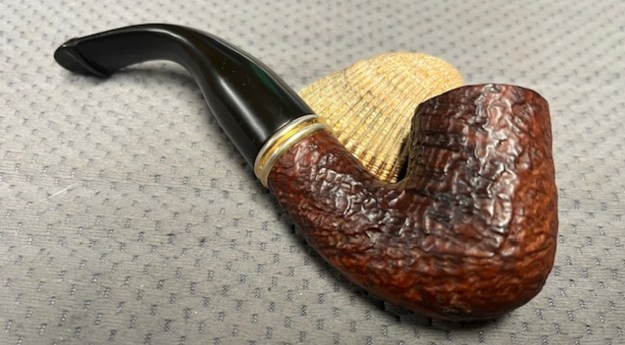

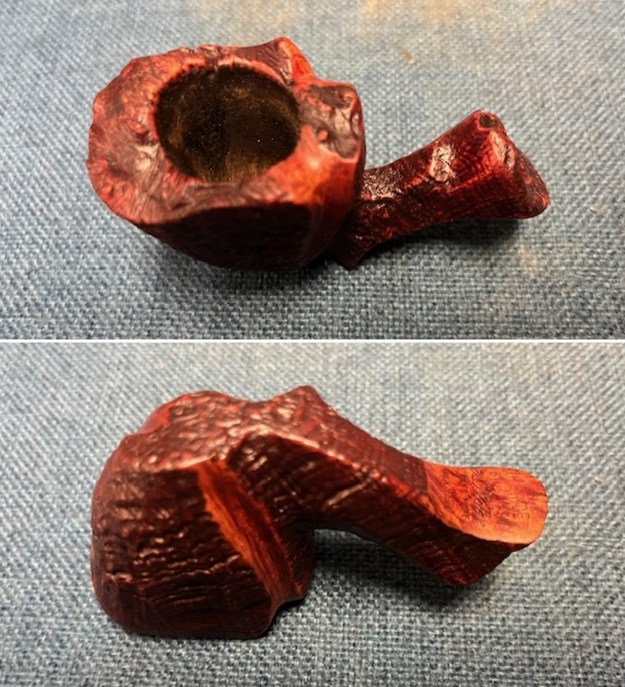

Jeff took photos of the sides and heel of the bowl to show the grain in the sandblast. It is a beautiful bowl. It is nice looking bent billiard and one is eye catching. Have a look.

Jeff took photos of the sides and heel of the bowl to show the grain in the sandblast. It is a beautiful bowl. It is nice looking bent billiard and one is eye catching. Have a look.

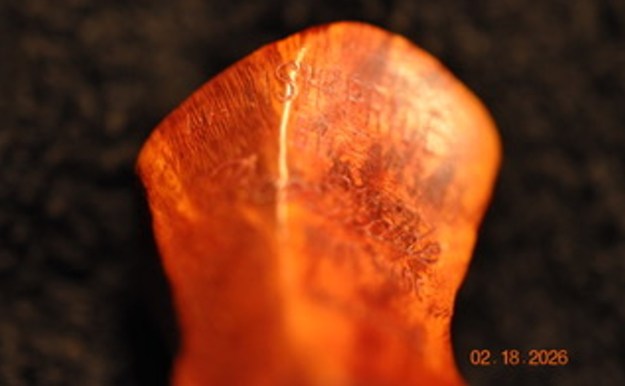

The next photos Jeff took show the stamping on a smooth portion on the underside of the shank. The stamping is faint in places but still readable as noted above.

The next photos Jeff took show the stamping on a smooth portion on the underside of the shank. The stamping is faint in places but still readable as noted above. I looked in my usual spots on Pipephil’s Stamping and Logo site as well as Pipedia to see what I could find on the Irish Whiskey line. There was nothing on either of those sites that I could find on the line.

I looked in my usual spots on Pipephil’s Stamping and Logo site as well as Pipedia to see what I could find on the Irish Whiskey line. There was nothing on either of those sites that I could find on the line.

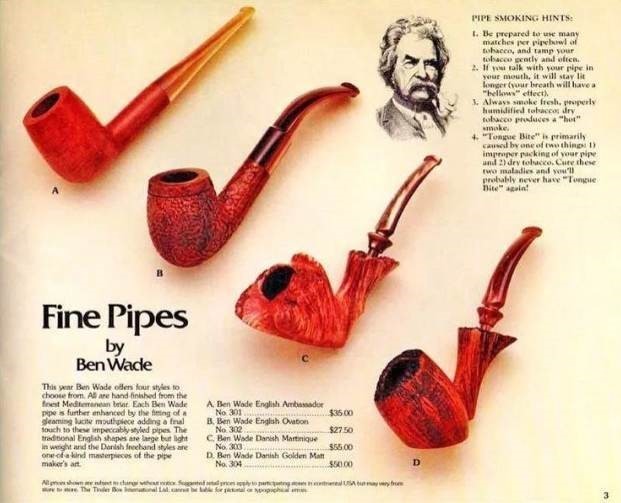

I googled the Peterson’s Irish Whiskey Line and found a link to the line on Mark Irwin’s Peterson’s Pipe Notes site (https://petersonpipenotes.org/sweet-petes-a-2015-gallery/). I turned to that and found the following information. I quote

The Irish Whisky line was available from 1997 to about 2005, and while the smooth finish was nice, the rustic has always popped for me and other Pete Nuts. When I saw not one but two of the rustic P-Lip Chubby 107s within a few weeks, I was amazed. Someday one will come around at the right time!

I then turned to The Peterson Pipe by Mark Irwin and Gary Malmberg. There on page 304 I found this information.

Irish Whiskey (1997-2005) Tan polished finish or sandblast line with brass domed double ring band, P-lip or fishtail mouth piece with brass P.

This gave me information regarding the date of the line. It was available between 1997-2005 and the description fit the pipe I have in hand. It is a sandblast pipe with the bands as described and a taper P-lip with a brass P logo on the left side of the stem.

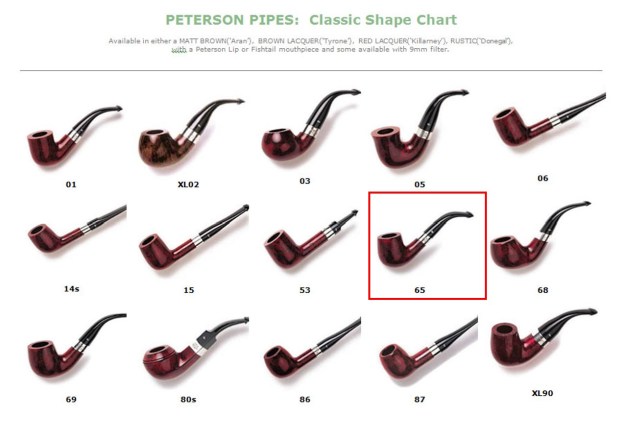

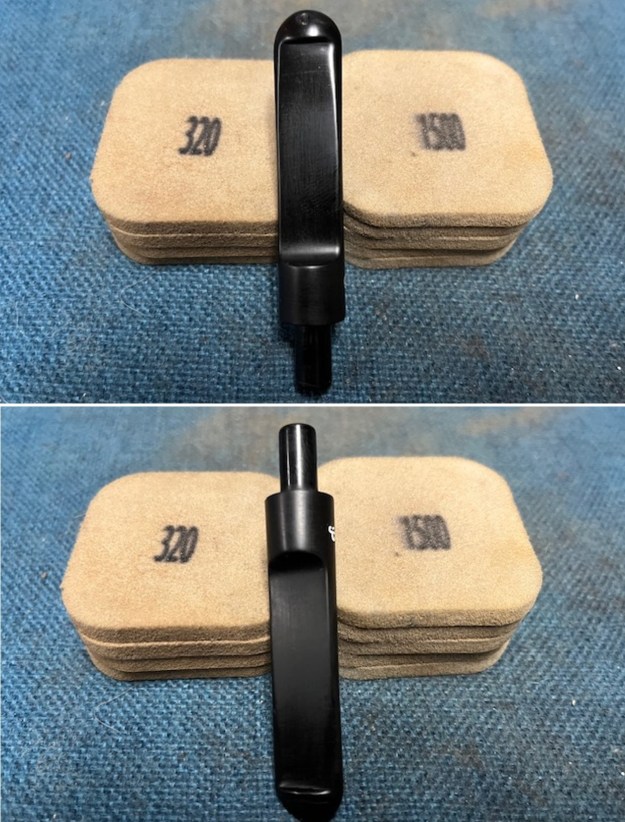

I did find a shape chart on the Pipedia site (https://pipedia.org/wiki/Peterson) that had the shape number 338 shown on it. I have drawn a red box around the shape on the second row of the chart below. Jeff had cleaned up the pipe following his normal cleaning process. In short, he reamed the bowl with a PipNet pipe reamer and took it back to briar. He then cleaned up the reaming with a Savinelli Fitsall Pipe Knife. He scrubbed the bowl with undiluted Murphy’s Oil Soap with a tooth brush. He worked over the lava and debris on the rim top and shank end and was able to remove it. He rinsed it under running warm water to remove the soap and grime. He cleaned out the inside of the shank and the airway in the stem with alcohol, cotton swabs, shank brushes and pipe cleaners. He scrubbed the stem with Soft Scrub and cotton pads to remove the debris and oils on the stem. He soaked it in Briarville’s Pipe Stem Deoxidizer to remove the remaining oxidation. He rinsed it with warm water and dried it off. I took photos of the pipe once I received it. It really looked good.

Jeff had cleaned up the pipe following his normal cleaning process. In short, he reamed the bowl with a PipNet pipe reamer and took it back to briar. He then cleaned up the reaming with a Savinelli Fitsall Pipe Knife. He scrubbed the bowl with undiluted Murphy’s Oil Soap with a tooth brush. He worked over the lava and debris on the rim top and shank end and was able to remove it. He rinsed it under running warm water to remove the soap and grime. He cleaned out the inside of the shank and the airway in the stem with alcohol, cotton swabs, shank brushes and pipe cleaners. He scrubbed the stem with Soft Scrub and cotton pads to remove the debris and oils on the stem. He soaked it in Briarville’s Pipe Stem Deoxidizer to remove the remaining oxidation. He rinsed it with warm water and dried it off. I took photos of the pipe once I received it. It really looked good.

I took close up photos of the stem and the rim top to show both how clean they were. The rim top and bowl look good. There is some slight damage in the blasted rim top on the back of the bowl.

I took close up photos of the stem and the rim top to show both how clean they were. The rim top and bowl look good. There is some slight damage in the blasted rim top on the back of the bowl. I took a photo of the stamping on the underside of the shank. You can see from the photo that it is faint but readable. I took a photo of the parts to give a sense of the beauty of the pipe.

I took a photo of the stamping on the underside of the shank. You can see from the photo that it is faint but readable. I took a photo of the parts to give a sense of the beauty of the pipe. The bowl was in such good condition after the clean up that I worked some Before & After Restoration Balm into the surface of the briar with my finger tips and a horse hair shoe brush to get into the crevices of the plateau and sandblast portions. The product is incredible and the way it brings the grain to the fore is unique. It works to clean, protect and invigorate the wood.

The bowl was in such good condition after the clean up that I worked some Before & After Restoration Balm into the surface of the briar with my finger tips and a horse hair shoe brush to get into the crevices of the plateau and sandblast portions. The product is incredible and the way it brings the grain to the fore is unique. It works to clean, protect and invigorate the wood.

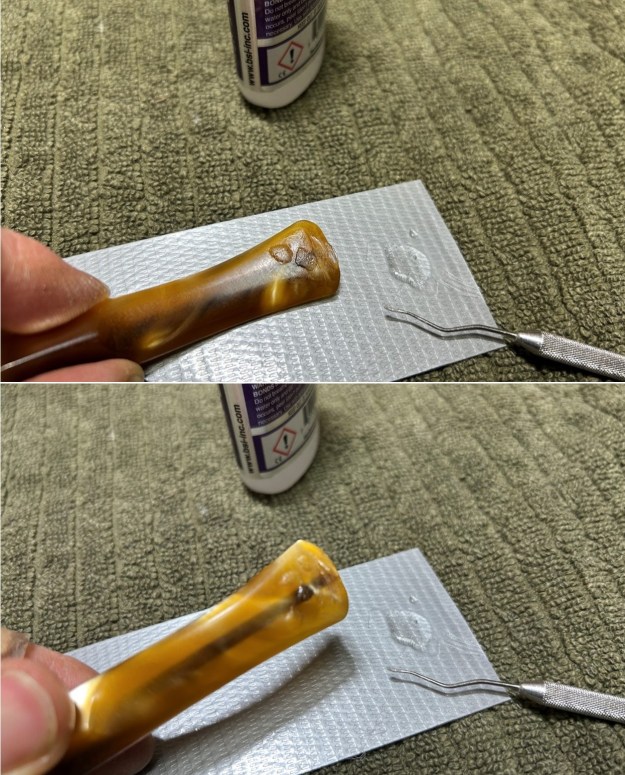

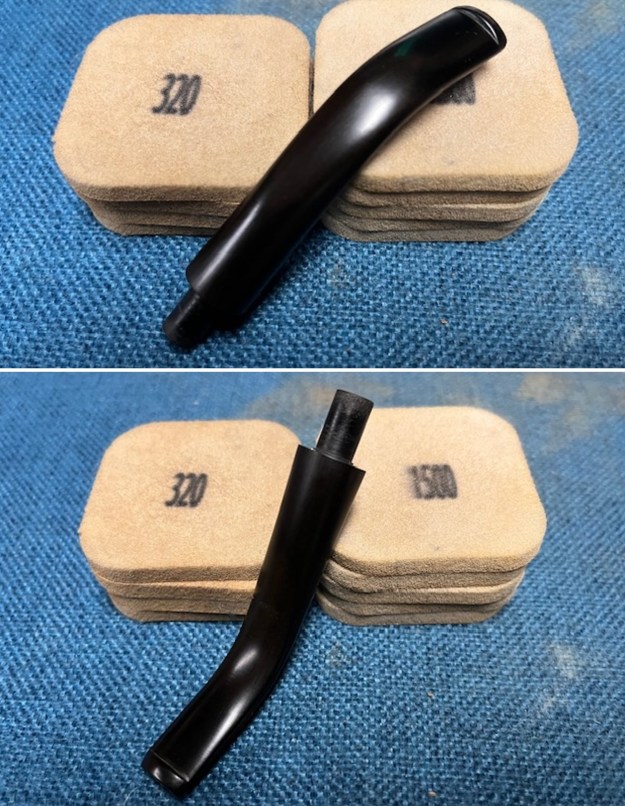

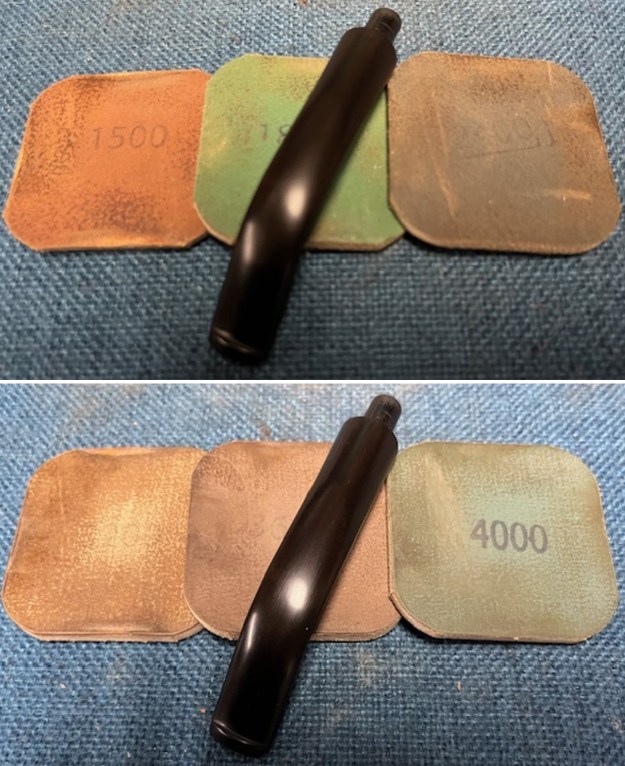

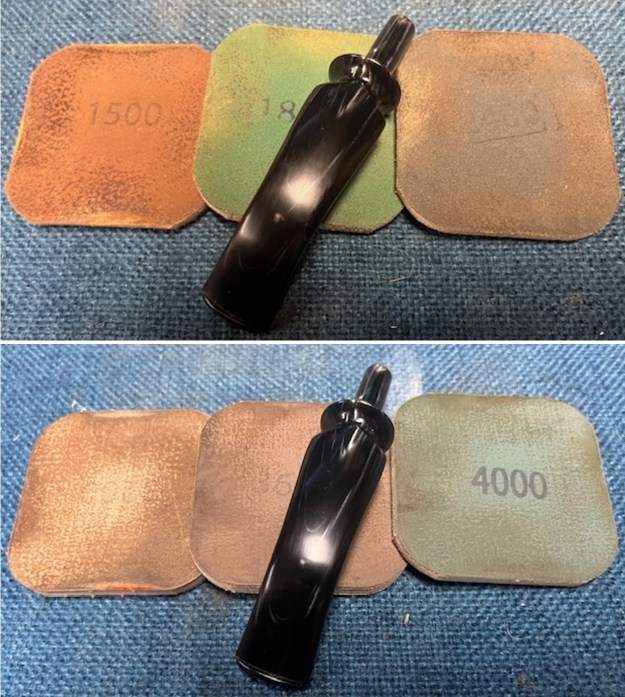

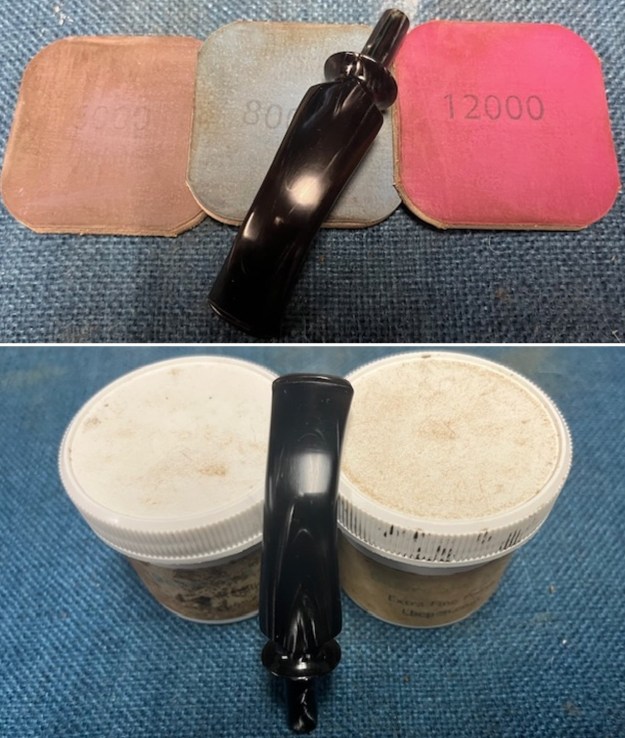

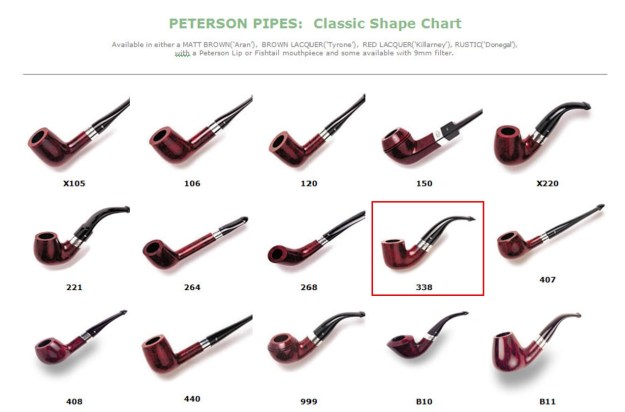

I set the bowl aside and turned my attention to the stem. I sanded out the tooth chatter and light marks on the underside of the stem with 320-3500 grit 2×2 inch sanding pads. I wiped the stem down with an Obsidian Oil cloth after each sanding pad. It began to look very good.

I set the bowl aside and turned my attention to the stem. I sanded out the tooth chatter and light marks on the underside of the stem with 320-3500 grit 2×2 inch sanding pads. I wiped the stem down with an Obsidian Oil cloth after each sanding pad. It began to look very good.  I polished the stem with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding it 1500-12000 pads. I wiped it down with Obsidian after each pad to remove the dust and polishing debris. I polished it with Before After Pipe Polish – both Fine and Extra Fine. I gave it another coat of Obsidian Oil.

I polished the stem with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding it 1500-12000 pads. I wiped it down with Obsidian after each pad to remove the dust and polishing debris. I polished it with Before After Pipe Polish – both Fine and Extra Fine. I gave it another coat of Obsidian Oil.

This Republic Era Peterson’s Irish Whiskey 65 Bent Billiard with three rings on the shank and a vulcanite taper stem with a P logo on the left side turned out very nice. The mix of brown stains highlights the grain in the sandblast around the bowl sides and bottom. The rim top and edges look very good. The finish on the pipe is in `excellent condition. I put the stem back on the bowl and carefully buffed the pipe with Blue Diamond on the buffing wheel. I gave the bowl and stem multiple coats of carnauba wax on the buffing wheel and followed that by buffing the entire pipe with a clean buffing pad. I hand buffed the pipe with a microfiber cloth to deepen the shine. The finished Peterson’s Irish Whiskey 65 Bent Billiard is very nice and feels great in the hand. Give the finished pipe a look in the photos below. It is a nice pipe whose dimensions are Length: 5 inches, Height: 1 ¾ inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 1/8 inches, Chamber diameter: ¾ of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 46 grams/1.62 ounces. Thanks for walking through the restoration with me as I worked over another beautiful pipe. This one will be going on the rebornpipes store, in the Irish Pipe Makers Section shortly. If you are interested in adding it to your collection let me know by message or by email to slaug@uniserve.com. Thanks for your time.

This Republic Era Peterson’s Irish Whiskey 65 Bent Billiard with three rings on the shank and a vulcanite taper stem with a P logo on the left side turned out very nice. The mix of brown stains highlights the grain in the sandblast around the bowl sides and bottom. The rim top and edges look very good. The finish on the pipe is in `excellent condition. I put the stem back on the bowl and carefully buffed the pipe with Blue Diamond on the buffing wheel. I gave the bowl and stem multiple coats of carnauba wax on the buffing wheel and followed that by buffing the entire pipe with a clean buffing pad. I hand buffed the pipe with a microfiber cloth to deepen the shine. The finished Peterson’s Irish Whiskey 65 Bent Billiard is very nice and feels great in the hand. Give the finished pipe a look in the photos below. It is a nice pipe whose dimensions are Length: 5 inches, Height: 1 ¾ inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 1/8 inches, Chamber diameter: ¾ of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 46 grams/1.62 ounces. Thanks for walking through the restoration with me as I worked over another beautiful pipe. This one will be going on the rebornpipes store, in the Irish Pipe Makers Section shortly. If you are interested in adding it to your collection let me know by message or by email to slaug@uniserve.com. Thanks for your time.

As always, I encourage your questions and comments as you read the blog. Thanks to each of you who are reading this blog. Remember we are not pipe owners; we are pipe men and women who hold our pipes in trust until they pass on into the trust of those who follow us.