Blog by Dal Stanton

When I study the venerable pipe on my work table, it is not a glamorous display of briar and silver bands. Some might call it a basket pipe. The two stars imprinted on the shank were an indication of a working man’s pipe – not high quality, but among those pipes accessible to normal, if not common, people who work, live, love and as is the case with us all, die. This unremarkable Apple shaped, BBB [diamond over] Double Star, MADE IN ENGLAND [over] 152, is remarkable because of the story it represents. I enjoy restoring ‘estate’ pipes because they were left to others and these pipes carry with them stories and memories of loved ones who once befriended and valued them. Greg heard from my son, Josiah, who are college buddies, that Josiah’s old man (my words not theirs!) restored ‘old’ pipes. This ‘old’ pipe came to Greg from his grandfather through his mother. Josiah’s email came to me asking what I could do with these pictures from Greg.

My understanding is that Greg was a bit reluctant at first to send his pipe off to Bulgaria to be restored, but after Josiah directed him to some of the restorations I’ve done, he felt he could trust me with the heirloom that had come to him. Knowing that this pipe was from his grandfather I asked that Greg send me information about his grandfather so that I not only could place the pipe better in history, but Greg’s grandfather as well. This is the letter he sent me:

My understanding is that Greg was a bit reluctant at first to send his pipe off to Bulgaria to be restored, but after Josiah directed him to some of the restorations I’ve done, he felt he could trust me with the heirloom that had come to him. Knowing that this pipe was from his grandfather I asked that Greg send me information about his grandfather so that I not only could place the pipe better in history, but Greg’s grandfather as well. This is the letter he sent me:

Hi Mr. Stanton,

Thank you so much for agreeing to restore my grandfather’s pipe. I am sorry for the delay in getting you the below information, but it’s been a crazy couple of weeks.

My mother inherited the pipe from my grandfather when he passed away in 1998. I saw it in the china cabinet one day and asked her if I could have it, since I had taken up pipe smoking. She kindly agreed. She doesn’t really know when my grandfather got the pipe, but she said he must have bought it in Hong Kong.

My grandfather was from Hong Kong, and only emigrated to the United States in the 1980s. He was a malaria inspector for the Hong Kong government for his entire working career. He must have gotten the pipe at the latest in the late 1940s or early 1950s, as my mother remembers him having it when she was a child. He never smoked the pipe when I knew him, but from its condition, I assume it was well used at an earlier period in his life.

Having graduated from the University of Georgia Law School in Athens, Georgia, passed his bars and currently serves as a law clerk to a federal magistrate judge in Augusta, Georgia, AND as a young married man, I can understand why Greg “took up” smoking pipes! Pipes are wonderful companions for blooming attorneys! His letter concluded with an agreement to the cost of the restoration would benefit our work with the Daughters of Bulgaria! Thank you, Greg!

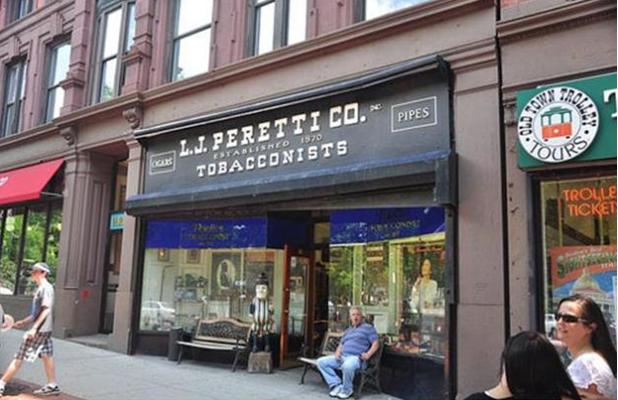

The information Greg received from his mother was invaluable for placing this BBB in time and space. Pipedia’s article about BBB is helpful. BBB in the mid-1800s originally stood for “Blumfeld’s Best Briars”, but after the death of Blumfeld, the Adolph Frankau Company took over the company and BBB gradually became “Britain’s Best Briars”.

The “BBB Two Star” rating also is referenced in the same article in a discussion of quality descriptors for BBB pipes:

In the Thirties, the top-of-the-range one becomes “BBB Best Make” with alternatives like “Super Stopping” and “Ultonia Thule”. The BBB Carlton, sold with the detail with 8/6 in 1938, is equipped with a system complicated out of metal, system which equipped the BBB London Dry too. Blue Peter was not estampillées BBB but BBB Ultonia, and the BBB Two Star (* *) become the bottom-of-the-range one.

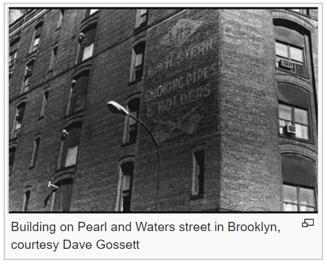

When Greg’s pipe arrived in Bulgaria, thanks to a visitor’s willingness to carry it across the Atlantic and European continent, I unwrapped it and put it on my work desk and took these pictures to fill in the gaps.

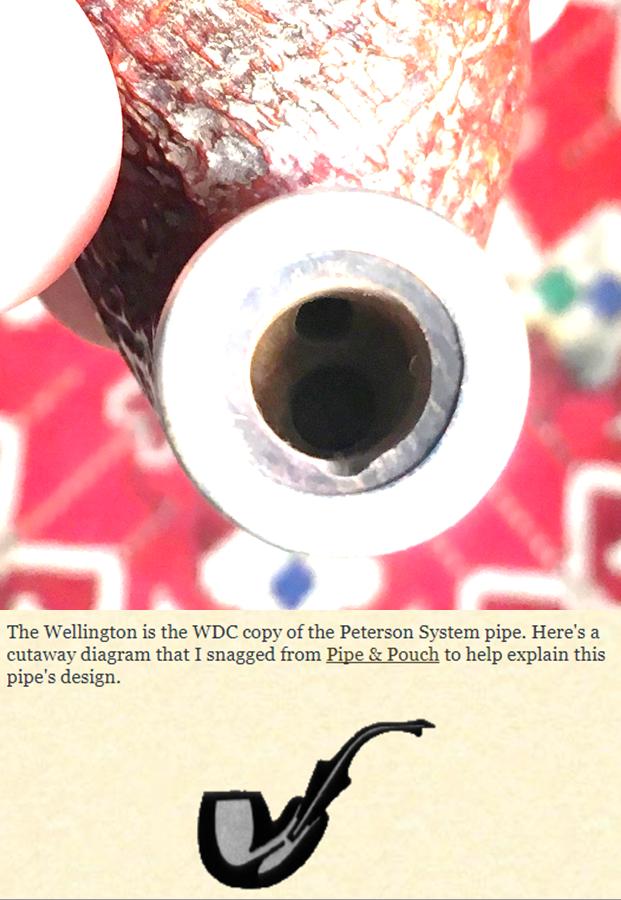

At PipePhil.eu an example of the BBB Two Star marking is pictured along with the stinger/tube style extending into the chamber as Greg’s grandfather’s BBB does ( as seen above).

At PipePhil.eu an example of the BBB Two Star marking is pictured along with the stinger/tube style extending into the chamber as Greg’s grandfather’s BBB does ( as seen above). In Pipes Magazine, I found a thread discussing the dating of the BBB Two Star. One threader’s opinion, ‘jguss’ corroborates Greg’s mother’s recollections:

In Pipes Magazine, I found a thread discussing the dating of the BBB Two Star. One threader’s opinion, ‘jguss’ corroborates Greg’s mother’s recollections:

My guess is that the Two Star line started at the end of WWII; the first mention I’ve found so far is dated 1945, which at least gives a tpq (that is, an approximate dating). I know the line lasted at least into the early sixties.

My guess is that the Two Star line started at the end of WWII; the first mention I’ve found so far is dated 1945, which at least gives a tpq (that is, an approximate dating). I know the line lasted at least into the early sixties.

It is not too difficult to speculate about the provenance of Greg’s pipe. During WW2, briar became a scarce commodity throughout Europe and pipe manufacturing companies made do with what they could acquire. Two Star BBBs would be lower end but more than likely during this time, a very close second when rations were short.  Added to this backdrop is the origin of our story in Hong Kong. Hong Kong, a British holding since 1841 (see LINK), lost control of Hong Kong during WW2 to Japan in 1941 during the Battle of Hong Kong. Undoubtedly, Greg’s grandfather would have experienced this first hand. When Japan unconditionally surrendered in 1945, the British regained control of Hong Kong, but to counter Chinese pressures to control Hong Kong, reforms were introduced that broadened and increased the stake of local inhabitants of Hong Kong:

Added to this backdrop is the origin of our story in Hong Kong. Hong Kong, a British holding since 1841 (see LINK), lost control of Hong Kong during WW2 to Japan in 1941 during the Battle of Hong Kong. Undoubtedly, Greg’s grandfather would have experienced this first hand. When Japan unconditionally surrendered in 1945, the British regained control of Hong Kong, but to counter Chinese pressures to control Hong Kong, reforms were introduced that broadened and increased the stake of local inhabitants of Hong Kong:

Sir Mark Young, upon his return as Governor in early May 1946, pursued political reform known as the “Young Plan“, believing that, to counter the Chinese government’s determination to recover Hong Kong, it was necessary to give local inhabitants a greater stake in the territory by widening the political franchise to include them.[19] (Link)

During the years following the Second World War, the same article describes unprecedented economic development which resulted in the economic powerhouse that Hong Kong became. This period would have been while Greg’s grandfather was working as a malaria inspector for the government of Hong Kong and during which he acquired this BBB Two Star. The smaller Apple shape would have served him well as he performed his inspection duties but given the ‘stem forensics’ pictured above, he probably chewed on it a bit as well while he worked!

With a greater sense of the story that this BBB Two Star tells, from England, to Hong Kong, to America, and now to Bulgaria, I’m anxious to restore this precious family gift from Greg’s grandfather. At Greg’s request, he’s hoping for a pipe that is as good as new and ready for a new lifetime of service. Yet, with all restorations, undoubtedly there will be some marks and blemishes remaining – these an ongoing testament to the memory of those who those who went before.

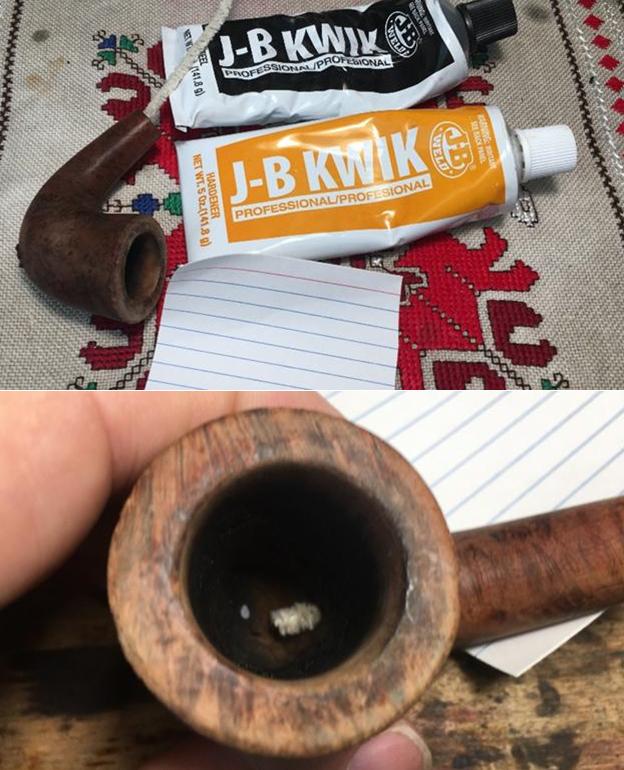

The first order of approach is with the stinger. When the pipe arrived, the stinger was already separated from the stem. The stinger extends from the stem through the mortise into the chamber itself through a metal tube air draft hole. Using a pair of plyers, I wrap a piece of cloth around the end to pull gently to dislodge the stinger from the mortise. I can see in the mortise that there appears to be a metal sheath that the stinger is lodged in – at least, that is what it appears to be. The stinger is not budging and I do not want to break the stinger off. To try to loosen things up, I pour some isopropyl 95% in the chamber to allow it to soak into the draft hole. Hopefully, in time, this will loosen the stinger.  The alcohol soak did not work. In fact, a few weeks have transpired since writing the words above. This stinger has given me quite the challenge. In the back of my mind constantly, is the concern that I not leverage too much pressure pulling on the stinger. I’m concerned about damaging the shank. After soaking the internals for some time with alcohol, I pulled with plyers hoping to break the grip. I also attempt heating the stummel with a heat gun in hope of dislodging the stinger. I also heat the protruding part of the stinger with a candle, hoping that this would break the bond. It did not. I also was concerned about the candle flame close to the briar while trying to heat the stinger. I craft a tinfoil shield, but this was not successful. Unfortunately, I singed the end of the shank and had to remove the damage by ‘topping’ the shank end, which leads to a bit of work lining up the stem and shank later. As you might expect, the protruding end of the stinger did not hold up under the pressure and eventually broke off.

The alcohol soak did not work. In fact, a few weeks have transpired since writing the words above. This stinger has given me quite the challenge. In the back of my mind constantly, is the concern that I not leverage too much pressure pulling on the stinger. I’m concerned about damaging the shank. After soaking the internals for some time with alcohol, I pulled with plyers hoping to break the grip. I also attempt heating the stummel with a heat gun in hope of dislodging the stinger. I also heat the protruding part of the stinger with a candle, hoping that this would break the bond. It did not. I also was concerned about the candle flame close to the briar while trying to heat the stinger. I craft a tinfoil shield, but this was not successful. Unfortunately, I singed the end of the shank and had to remove the damage by ‘topping’ the shank end, which leads to a bit of work lining up the stem and shank later. As you might expect, the protruding end of the stinger did not hold up under the pressure and eventually broke off.

After the stinger protrusion broke off, and after a second email to Steve for input, I’m at the point of using a drill bit in another attempt to remove the bonded stinger. Starting with a very small bit, I hand turn the bit to allow the drill to find the center of the stinger and gradually, remove the stinger introducing the next larger drill bit. The end of the broken stinger begins at about 1/4-inch-deep into the mortise. Unfortunately, this method is not working either because the drill bit will not bite into the metal and remain straight. At the end of the stinger slot that I’m boring into with the drill bit, my efforts are flummoxed by the stinger’s design. It has a slanted metal airflow deflector that causes the drill bit to veer off mark.

After the stinger protrusion broke off, and after a second email to Steve for input, I’m at the point of using a drill bit in another attempt to remove the bonded stinger. Starting with a very small bit, I hand turn the bit to allow the drill to find the center of the stinger and gradually, remove the stinger introducing the next larger drill bit. The end of the broken stinger begins at about 1/4-inch-deep into the mortise. Unfortunately, this method is not working either because the drill bit will not bite into the metal and remain straight. At the end of the stinger slot that I’m boring into with the drill bit, my efforts are flummoxed by the stinger’s design. It has a slanted metal airflow deflector that causes the drill bit to veer off mark.  After breaking the end of the drill bit in the slot (ugh!), and digging it out with needle nose pliers, I sit and begin to think I was facing failure. Nothing was working. I’m introducing more problems to the restoration as I try unsuccessfully to solve the stuck stinger problem. I can’t move forward and I’m stuck and begin to compose an apology letter to Greg in my mind. UNTIL, on a fancy, I insert a small flat head screw driver into the slot at the end of the broken stinger 1/4-inch-deep in the mortise and I twist it gently counter-clockwise, and it snaps. Suddenly, it was loose and I easily extract the ‘middle’ of Grandpa’s old stinger – I’m sure he was the last one to see this artifact! I see daylight through the mortise and I’m hoping that it might also be a metaphoric ‘light at the end of the tunnel’! I’ve not forgotten that the other end of the stinger remains lodged in the draft hole tube at the foot of the chamber. Thankfully, a larger drill bit was the perfect size and it reaches into the mortise and hand turning the bit, it clears the rest of the stinger shrapnel. Finally! Oh my…. I’ll be saving the stinger debris for Greg. This BBB will continue without difficulty stingerless. The pictures show the results.

After breaking the end of the drill bit in the slot (ugh!), and digging it out with needle nose pliers, I sit and begin to think I was facing failure. Nothing was working. I’m introducing more problems to the restoration as I try unsuccessfully to solve the stuck stinger problem. I can’t move forward and I’m stuck and begin to compose an apology letter to Greg in my mind. UNTIL, on a fancy, I insert a small flat head screw driver into the slot at the end of the broken stinger 1/4-inch-deep in the mortise and I twist it gently counter-clockwise, and it snaps. Suddenly, it was loose and I easily extract the ‘middle’ of Grandpa’s old stinger – I’m sure he was the last one to see this artifact! I see daylight through the mortise and I’m hoping that it might also be a metaphoric ‘light at the end of the tunnel’! I’ve not forgotten that the other end of the stinger remains lodged in the draft hole tube at the foot of the chamber. Thankfully, a larger drill bit was the perfect size and it reaches into the mortise and hand turning the bit, it clears the rest of the stinger shrapnel. Finally! Oh my…. I’ll be saving the stinger debris for Greg. This BBB will continue without difficulty stingerless. The pictures show the results.

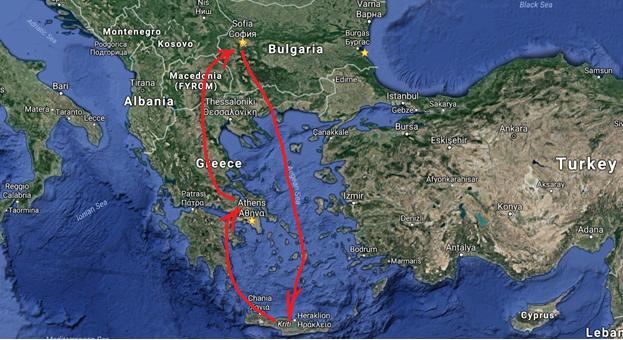

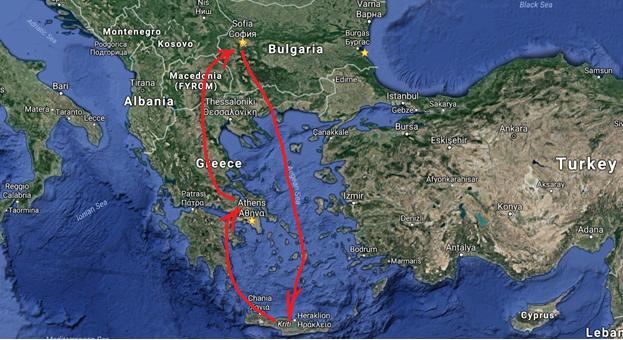

In the interest of full disclosure, these words are coming weeks after. Why the hiatus? Life’s normal twists and turns, work, some wonderful travel to Crete for an organizational conference, to Athens (not in Georgia) for a consultation on the Eastern Orthodox Church, AND my growing frustration with Greg’s grandfather’s pipe’s restoration as more complications arrived! I’ll try to catch you up to the present:

In the interest of full disclosure, these words are coming weeks after. Why the hiatus? Life’s normal twists and turns, work, some wonderful travel to Crete for an organizational conference, to Athens (not in Georgia) for a consultation on the Eastern Orthodox Church, AND my growing frustration with Greg’s grandfather’s pipe’s restoration as more complications arrived! I’ll try to catch you up to the present:

With the stinger removed, I was anxious to continue the restoration with a ‘normal’ pattern – the stem goes into the Oxi-Clean bath to deal with the oxidation in the stem. After some hours, the stem is removed from the bath and I wet sand with 600 grade sanding paper removing the raised oxidation followed by 0000 steel wool. To clean and protect the BBB stamping on the stem, I use a non-abrasive Mr. Clean ‘Magic Eraser’ sponge. The pictures show the progress. The next step is to re-seat the tenon into the mortise. After the arduous process of removing the stinger, and after singing the shank end with a candle flame, and after ‘topping’ the shank to remove the damaged briar, the tenon and mortise needed to be re-wedded with the new realities. The tenon was too large for full insertion into the shank. Using a combination of reducing the tenon size with sanding paper and steel wool, sanding and filing the throat of the mortise, and using a rounded needle file to cut a new internal mortise openning bevel to accommodate the broader tenon base, I patiently, slowly, methodically worked to re-seat the tenon in the mortise which included working and then testing the new fit – GENTLY! I suppose the fact that I said to myself, ‘Dal, careful, don’t crack the shank’, at least a 1000 times only made the sinking feeling more intense when I heard the sickening sound during what proved to be my last, ‘gentle testing’ of the tenon inserted into the mortise. The hairline crack is pictured below that I took only a day ago – I couldn’t bear to take it then, when it happened. I was sickened and put Greg’s pipe aside. I needed some time to work through my own sense of failure of the trust given me to restore this family heirloom.

The next step is to re-seat the tenon into the mortise. After the arduous process of removing the stinger, and after singing the shank end with a candle flame, and after ‘topping’ the shank to remove the damaged briar, the tenon and mortise needed to be re-wedded with the new realities. The tenon was too large for full insertion into the shank. Using a combination of reducing the tenon size with sanding paper and steel wool, sanding and filing the throat of the mortise, and using a rounded needle file to cut a new internal mortise openning bevel to accommodate the broader tenon base, I patiently, slowly, methodically worked to re-seat the tenon in the mortise which included working and then testing the new fit – GENTLY! I suppose the fact that I said to myself, ‘Dal, careful, don’t crack the shank’, at least a 1000 times only made the sinking feeling more intense when I heard the sickening sound during what proved to be my last, ‘gentle testing’ of the tenon inserted into the mortise. The hairline crack is pictured below that I took only a day ago – I couldn’t bear to take it then, when it happened. I was sickened and put Greg’s pipe aside. I needed some time to work through my own sense of failure of the trust given me to restore this family heirloom.

Now, after several weeks, I’ve regrouped and have taken up Greg’s pipe again. The travels that I described above during this time in some ways felt more like Jonah running from Nineveh not wanting to face the scene of his calling and his sense of failure! Though, my trip did prove beneficial – I sold some of my finished pipes to colleagues to benefit and raise the awareness of the Daughters of Bulgaria that The Pipe Steward supports. I’ve included my Nineveh travels below for you who may not be familiar with ‘my world’, the Balkans – Sofia to Crete to Athens and back.

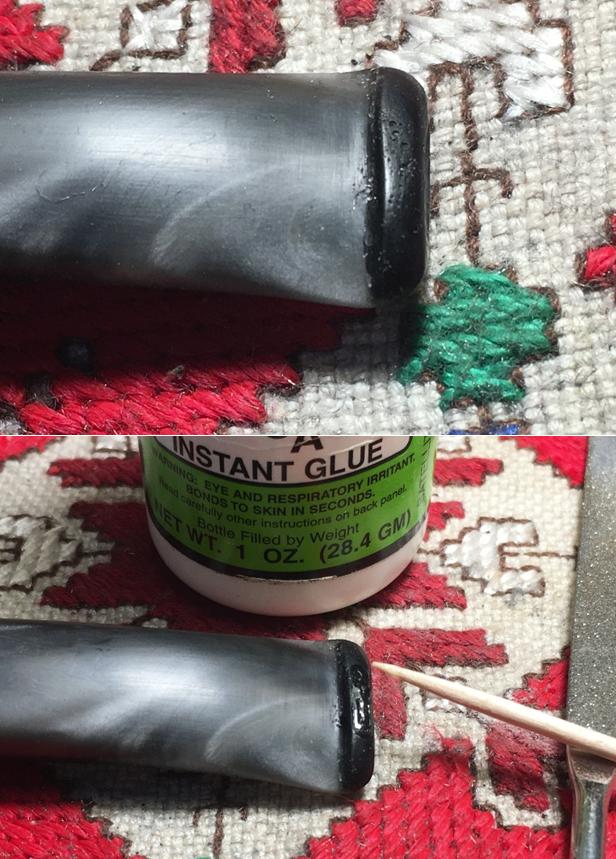

Now, after several weeks, I’ve regrouped and have taken up Greg’s pipe again. The travels that I described above during this time in some ways felt more like Jonah running from Nineveh not wanting to face the scene of his calling and his sense of failure! Though, my trip did prove beneficial – I sold some of my finished pipes to colleagues to benefit and raise the awareness of the Daughters of Bulgaria that The Pipe Steward supports. I’ve included my Nineveh travels below for you who may not be familiar with ‘my world’, the Balkans – Sofia to Crete to Athens and back.  Before moving forward, I needed to repair the cracked shank. With the help of a magnifying glass, I locate the terminus of the crack and mark it by creating an indentation with a sharp dental probe. The arrow to the left below marks this. Using the Dremel tool, I mount a 1mm sized bit and drill a hole at that point – but not going through! This hole acts like a controlled back-fire to stop the progress of a forest fire. This will not allow the crack to continue creeping. With the use of a toothpick, I spot-drop Hot Stuff CA Instant Glue in the hole and along the line of the crack which I expanded microscopically by partially inserting the tenon into the mortise. This allows the CA glue better penetration to seal the crack. I remove the stem immediately after the application of CA. With the CA glue still wet, I apply briar dust to/in the hole and along the crack to encourage better blending. The pictures show the progress.

Before moving forward, I needed to repair the cracked shank. With the help of a magnifying glass, I locate the terminus of the crack and mark it by creating an indentation with a sharp dental probe. The arrow to the left below marks this. Using the Dremel tool, I mount a 1mm sized bit and drill a hole at that point – but not going through! This hole acts like a controlled back-fire to stop the progress of a forest fire. This will not allow the crack to continue creeping. With the use of a toothpick, I spot-drop Hot Stuff CA Instant Glue in the hole and along the line of the crack which I expanded microscopically by partially inserting the tenon into the mortise. This allows the CA glue better penetration to seal the crack. I remove the stem immediately after the application of CA. With the CA glue still wet, I apply briar dust to/in the hole and along the crack to encourage better blending. The pictures show the progress.

After some hours allowing the CA glue to cure on the shank repair, using a round grinding stone bit mounted on the Dremel, I reestablish an adequate and uniform internal bevel on the end of the shank to accommodate the base of the tenon when it is fully inserted into the mortise. My theory is this is what caused the crack – lack of a sufficient internal bevel giving room for the slightly enlarged tenon as it merges with the stem proper. With the Dremel engaged at the slowest setting, I’m careful to apply minimal pressure as I rotate the ball a bit to make sure it’s centered. It looks good – the pictures show the progress.

After some hours allowing the CA glue to cure on the shank repair, using a round grinding stone bit mounted on the Dremel, I reestablish an adequate and uniform internal bevel on the end of the shank to accommodate the base of the tenon when it is fully inserted into the mortise. My theory is this is what caused the crack – lack of a sufficient internal bevel giving room for the slightly enlarged tenon as it merges with the stem proper. With the Dremel engaged at the slowest setting, I’m careful to apply minimal pressure as I rotate the ball a bit to make sure it’s centered. It looks good – the pictures show the progress. Due to a lapse of sorts and the intensity of my focus on re-seating the stem again without re-cracking the shank, I failed (or perhaps, had little desire) to take any pictures. The short of it is, the stem and stummel have been reunited after some difficult times. Also, not pictured are some of the basic steps: reaming the fire chamber of carbon cake buildup, cleaning the internals of the stummel and stem with cotton swabs and pipe cleaners wetted with isopropyl 95%, and cleaning the externals of the stummel with Murphy’s Soap. Again, picking up the trail, pictured below is the micromesh pad process with the stem. Using pads 1500 to 2400, I wet sand the stem, followed by dry sanding with pads 3200 to 4000 and then 6000 to 12000. I follow each cycle with an application of Obsidian Oil to revitalize the vulcanite.

Due to a lapse of sorts and the intensity of my focus on re-seating the stem again without re-cracking the shank, I failed (or perhaps, had little desire) to take any pictures. The short of it is, the stem and stummel have been reunited after some difficult times. Also, not pictured are some of the basic steps: reaming the fire chamber of carbon cake buildup, cleaning the internals of the stummel and stem with cotton swabs and pipe cleaners wetted with isopropyl 95%, and cleaning the externals of the stummel with Murphy’s Soap. Again, picking up the trail, pictured below is the micromesh pad process with the stem. Using pads 1500 to 2400, I wet sand the stem, followed by dry sanding with pads 3200 to 4000 and then 6000 to 12000. I follow each cycle with an application of Obsidian Oil to revitalize the vulcanite.

The stummel surface shows quite a bit of pitting in the first picture shown again below. The rim also shows nicks. On the larger pits shown below on the heel of the stummel, I spot-fill with a toothpick using CA glue and shorten the curing time by using an accelerator spray on the fills. After filing and sanding the fills to the briar surface, using a progression of 3 sanding sponges from coarse, medium to light, I work out most the remaining pitting over the stummel surface. Using 600 grit paper on the chopping block, I also give a light topping to the rim to remove nicks and create fresh lines for the rim. Following the topping, I introduce an internal bevel to the rim, first using a coarse 120 paper rolled tightly, then with 240 and 600. The internal rim bevel to me, always adds a touch of class but also helps create softer lines which enhances this Apples shape. The pictures show the unhindered progress!

The stummel surface shows quite a bit of pitting in the first picture shown again below. The rim also shows nicks. On the larger pits shown below on the heel of the stummel, I spot-fill with a toothpick using CA glue and shorten the curing time by using an accelerator spray on the fills. After filing and sanding the fills to the briar surface, using a progression of 3 sanding sponges from coarse, medium to light, I work out most the remaining pitting over the stummel surface. Using 600 grit paper on the chopping block, I also give a light topping to the rim to remove nicks and create fresh lines for the rim. Following the topping, I introduce an internal bevel to the rim, first using a coarse 120 paper rolled tightly, then with 240 and 600. The internal rim bevel to me, always adds a touch of class but also helps create softer lines which enhances this Apples shape. The pictures show the unhindered progress!

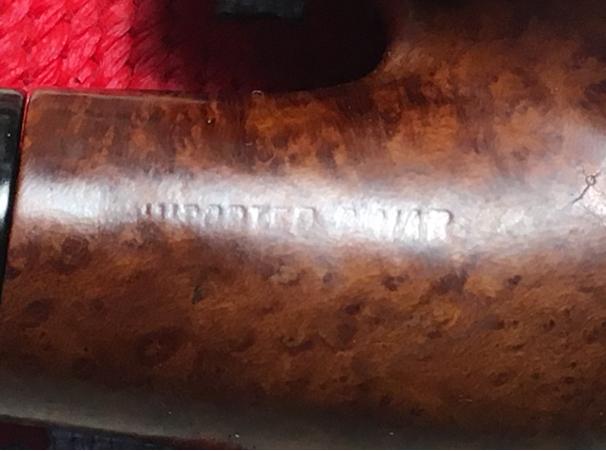

I now take micromesh pads 1500 to 2400 and wet sand the stummel followed by dry sanding with micromesh pads 3200 to 4000 and then 6000 to 12000 taking a picture after each set to mark the progress. I am careful to guard the BBB nomenclature on the shank sides. As I move through these cycles, I realize that I have been so wrapped up in the technical aspects of this restoration for Greg, that I failed to see the beauty of this diminutive Apple shape. The grain that emerges from Grandpa’s old timer is truly beautiful. Flame grain and swirls, with a few bird’s eyes accenting the whole – totally eye-catching for a Two Star sub-mark BBB I would say!

I now take micromesh pads 1500 to 2400 and wet sand the stummel followed by dry sanding with micromesh pads 3200 to 4000 and then 6000 to 12000 taking a picture after each set to mark the progress. I am careful to guard the BBB nomenclature on the shank sides. As I move through these cycles, I realize that I have been so wrapped up in the technical aspects of this restoration for Greg, that I failed to see the beauty of this diminutive Apple shape. The grain that emerges from Grandpa’s old timer is truly beautiful. Flame grain and swirls, with a few bird’s eyes accenting the whole – totally eye-catching for a Two Star sub-mark BBB I would say!

To see the big picture to help determine the next steps, I reunite stem and stummel and stand back and take a good look. This BBB Made in England is looking real good – in spite of everything! I can see by the way the BBB Apple naturally sits on the surface, leaning slightly like a listing ship, but remaining upright, provides some clues regarding the significant pitting on the heel of the stummel – just off center. Greg’s grandfather undoubtedly and conveniently placed his pipe on a table or counter surface, or perhaps on a nearby crate, as he made his rounds as a malaria inspector for the province of Hong Kong.

To see the big picture to help determine the next steps, I reunite stem and stummel and stand back and take a good look. This BBB Made in England is looking real good – in spite of everything! I can see by the way the BBB Apple naturally sits on the surface, leaning slightly like a listing ship, but remaining upright, provides some clues regarding the significant pitting on the heel of the stummel – just off center. Greg’s grandfather undoubtedly and conveniently placed his pipe on a table or counter surface, or perhaps on a nearby crate, as he made his rounds as a malaria inspector for the province of Hong Kong.  The original BBB coloring leaned toward the favored darker hues of English pipe makers and client proclivities. I decide not to go that dark, but to stain the stummel using a light brown base with a touch of dark brown to tint it down that track a bit. This will make for better blending, especially for the darker briar around the nomenclature on the shank. Using Fiebing’s Light Brown Leather Dye as the base, I add a touch of Fiebing’s Dark Brown. Using a folded pipe cleaner in the shank as a handle, I begin by warming the stummel with a hot air gun to expand the briar making it more receptive to the dye. After heated, I apply the dye mixture to the stummel generously aiming for total coverage. I then fire the wet stummel with a lit candle igniting the aniline dye, burning off the alcohol and setting the pigment in the grain. After a few minutes, I repeat the process concluding with firing the stummel. I put the stummel aside to rest for several hours. The pictures show the staining process – yes, you can see my blue fingers – I’ve started wearing latex gloves when I’m staining.

The original BBB coloring leaned toward the favored darker hues of English pipe makers and client proclivities. I decide not to go that dark, but to stain the stummel using a light brown base with a touch of dark brown to tint it down that track a bit. This will make for better blending, especially for the darker briar around the nomenclature on the shank. Using Fiebing’s Light Brown Leather Dye as the base, I add a touch of Fiebing’s Dark Brown. Using a folded pipe cleaner in the shank as a handle, I begin by warming the stummel with a hot air gun to expand the briar making it more receptive to the dye. After heated, I apply the dye mixture to the stummel generously aiming for total coverage. I then fire the wet stummel with a lit candle igniting the aniline dye, burning off the alcohol and setting the pigment in the grain. After a few minutes, I repeat the process concluding with firing the stummel. I put the stummel aside to rest for several hours. The pictures show the staining process – yes, you can see my blue fingers – I’ve started wearing latex gloves when I’m staining.

After some hours, I’m looking forward to ‘unwrapping’ the fired stummel to reveal the stained briar beneath. Using a felt buffing wheel mounted on the Dremel, set at the slowest speed, I use Tripoli compound to remove the initial layer. Moving in a methodical, rotating pattern, I work my way around the stummel not apply a great deal of down-pressure on the wheel, but allowing the RPMs of the felt wheel and the compound to do the work. After removing the crusted layer with Tripoli, I wipe the surface with a cotton pad wetted with isopropyl 95%. I do this not so much to lighten the finish, but to blend and even out the stain over the surface. Following this, I mount a cotton cloth wheel on the Dremel, increase the speed slightly, and apply Blue Diamond – a slightly less abrasive compound. After both compounds, I use a clean towel to hand buff the stummel to remove excess compound dust before applying the wax. Pictures show the progress.

After some hours, I’m looking forward to ‘unwrapping’ the fired stummel to reveal the stained briar beneath. Using a felt buffing wheel mounted on the Dremel, set at the slowest speed, I use Tripoli compound to remove the initial layer. Moving in a methodical, rotating pattern, I work my way around the stummel not apply a great deal of down-pressure on the wheel, but allowing the RPMs of the felt wheel and the compound to do the work. After removing the crusted layer with Tripoli, I wipe the surface with a cotton pad wetted with isopropyl 95%. I do this not so much to lighten the finish, but to blend and even out the stain over the surface. Following this, I mount a cotton cloth wheel on the Dremel, increase the speed slightly, and apply Blue Diamond – a slightly less abrasive compound. After both compounds, I use a clean towel to hand buff the stummel to remove excess compound dust before applying the wax. Pictures show the progress.

Reattaching the stem and stummel, I apply several coats of carnauba wax to both. Using a cotton cloth wheel, I set the speed of the Dremel to 2 with 5 being the fastest, I apply the carnauba and I like what I see. With the carnauba wax applied, I mount a clean cotton cloth buffing wheel on the Dremel and again buff the stummel and stem. Finally, I apply a rigorous hand buff using a micromesh cloth to raise the shine more.

Reattaching the stem and stummel, I apply several coats of carnauba wax to both. Using a cotton cloth wheel, I set the speed of the Dremel to 2 with 5 being the fastest, I apply the carnauba and I like what I see. With the carnauba wax applied, I mount a clean cotton cloth buffing wheel on the Dremel and again buff the stummel and stem. Finally, I apply a rigorous hand buff using a micromesh cloth to raise the shine more.

This BBB Double Star Apple has come a long way from England to Hong Kong to the US to Bulgaria, and now it’s ready to return to its new steward. This restoration was a bit bumpy, but then, so is life. I’m glad to help give this pipe a new lifetime and I hope Greg not only enjoys it, but that it provides a special connection with his past. I’m sure Grandpa would be proud. Thanks for joining me!

When I bring the BC to my worktable, I take additional pictures to fill in the gaps.

When I bring the BC to my worktable, I take additional pictures to fill in the gaps.

The nomenclature is stamped on the lower side of the shank with the left side of the stamping reading in a fancy script, ‘Choquin’ [over] ‘Cadre Noir’ which means in French according to Google Translate, ‘Black Framework’ or ‘Black Setting’. On the right side of the stamping is an arched ST CLAUDE [over] FRANCE [over] 1845 – which I’m assuming is a shape number. Pipephil was helpful in identifying the 1845 as a shape number. The C’est bon below is the same BC pipe shape in a smooth version, which I described above as a Leprechaun – perhaps a mix between freehand and Dublin? The bowl moves from a wide rim, a narrower mid-section and then flares out again at the heel with ridges tapering toward the shank. Very nice looking.

The nomenclature is stamped on the lower side of the shank with the left side of the stamping reading in a fancy script, ‘Choquin’ [over] ‘Cadre Noir’ which means in French according to Google Translate, ‘Black Framework’ or ‘Black Setting’. On the right side of the stamping is an arched ST CLAUDE [over] FRANCE [over] 1845 – which I’m assuming is a shape number. Pipephil was helpful in identifying the 1845 as a shape number. The C’est bon below is the same BC pipe shape in a smooth version, which I described above as a Leprechaun – perhaps a mix between freehand and Dublin? The bowl moves from a wide rim, a narrower mid-section and then flares out again at the heel with ridges tapering toward the shank. Very nice looking. Searching for the BC Cadre Noir online, one finds several examples of what TobaccoPipes.com describes as a BC line depicting a “modern pipe”.

Searching for the BC Cadre Noir online, one finds several examples of what TobaccoPipes.com describes as a BC line depicting a “modern pipe”.

Now looking to the external rustified surface, I use Murphy’s Oil Soap undiluted with a cotton pad and a bristled tooth brush to get into the nooks and crannies of the surface. The pictures show the cleaning.

Now looking to the external rustified surface, I use Murphy’s Oil Soap undiluted with a cotton pad and a bristled tooth brush to get into the nooks and crannies of the surface. The pictures show the cleaning.

Switching to the internals, I use pipe cleaners and cotton swabs to do the job. When I realize my time is waning, I decide to complete the internal cleaning and refreshing with the use of a salt – alcohol bath. Using kosher salt, I fill the bowl, and stretch and twist a cotton ball to create a wick to stuff down the mortise. I fill the bowl with alcohol until it surfaces over the salt and I put it aside to let it soak for several hours.

Switching to the internals, I use pipe cleaners and cotton swabs to do the job. When I realize my time is waning, I decide to complete the internal cleaning and refreshing with the use of a salt – alcohol bath. Using kosher salt, I fill the bowl, and stretch and twist a cotton ball to create a wick to stuff down the mortise. I fill the bowl with alcohol until it surfaces over the salt and I put it aside to let it soak for several hours.

The soak did the job when I return home later that day. The salt and wick had absorbed the oils and tars from the briar. I toss the old salt, wipe the chamber with paper towel and use a bristle brush to remove all the salt residue. I return to using cotton swabs and as billed, the soak had done the job. The pictures show the cleaning process.

The soak did the job when I return home later that day. The salt and wick had absorbed the oils and tars from the briar. I toss the old salt, wipe the chamber with paper towel and use a bristle brush to remove all the salt residue. I return to using cotton swabs and as billed, the soak had done the job. The pictures show the cleaning process. Now to the acrylic stem. I first clean the internals which were in great shape.

Now to the acrylic stem. I first clean the internals which were in great shape. The major challenge I face with this BC Cadre Noir 1845, is the acrylic stem button repair. I did a repair on a Meerschaum’s Bakelite stem which was a clinic in trial and error, but finally realizing success. That Meerschaum is now a good friend in my rotation and you can see the Bakelite stem repair at The Pipe Steward blog site here: LINK. I take some additional close-ups of the chipped button.

The major challenge I face with this BC Cadre Noir 1845, is the acrylic stem button repair. I did a repair on a Meerschaum’s Bakelite stem which was a clinic in trial and error, but finally realizing success. That Meerschaum is now a good friend in my rotation and you can see the Bakelite stem repair at The Pipe Steward blog site here: LINK. I take some additional close-ups of the chipped button.

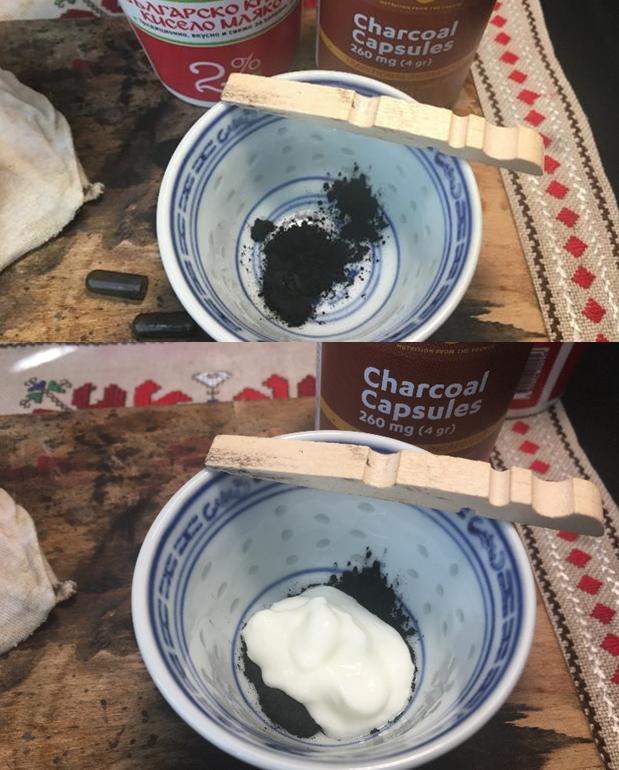

This acrylic stem has a gray marble color. The good news is that the lower button (pictured above) is intact and acts as a template for the upper button rebuild. The challenge is matching the patch material color with the multi-colored hues of gray. My idea of how to approach this is to use clear thick CA glue as a base. I will mix some white acrylic paint with it to create the light base. Then, I will very gradually add activated charcoal to the mixture to create the movement toward the grays. I have no idea how the white acrylic paint and the CA glue will react together. I begin this repair using a needle file to work on the button while its exposed – filing down the lower surface of the slot which is rough from the break. I then cut an index card forming a triangle, cover it with scotch tape which prevents the patch material from adhering to it, and insert it into the slot acting as a mold. The mold will shape the slot area as well as guard the airway from the patch material seeping into it and clogging it.

This acrylic stem has a gray marble color. The good news is that the lower button (pictured above) is intact and acts as a template for the upper button rebuild. The challenge is matching the patch material color with the multi-colored hues of gray. My idea of how to approach this is to use clear thick CA glue as a base. I will mix some white acrylic paint with it to create the light base. Then, I will very gradually add activated charcoal to the mixture to create the movement toward the grays. I have no idea how the white acrylic paint and the CA glue will react together. I begin this repair using a needle file to work on the button while its exposed – filing down the lower surface of the slot which is rough from the break. I then cut an index card forming a triangle, cover it with scotch tape which prevents the patch material from adhering to it, and insert it into the slot acting as a mold. The mold will shape the slot area as well as guard the airway from the patch material seeping into it and clogging it.

Well, mixing white acrylic paint with CA glue doesn’t work, so don’t try that path! The paint immediately gummed up as it was mixed and did not provide a lightening effect. To build the button, I end up simply applying thick CA glue and charcoal powder mixture to the button and spraying it with an accelerator to shorten the curing time. It doesn’t have the gray hue I was wanting to blend better, but it should look ok after sanding and shaping. I pull out the index mold and the slot looks rough now, but good. Using a flat needle file, I start shaping the button lip. Without a doubt – in my opinion, button rebuilding is the most time consuming and meticulous aspect of restoring estate pipes. Patiently, I file the button and slot to a shape that is consistent with the original button curvature. Using the lower lip as the template, I shape, file, shape, file…. It’s looking good. Pictures show the progress.

Well, mixing white acrylic paint with CA glue doesn’t work, so don’t try that path! The paint immediately gummed up as it was mixed and did not provide a lightening effect. To build the button, I end up simply applying thick CA glue and charcoal powder mixture to the button and spraying it with an accelerator to shorten the curing time. It doesn’t have the gray hue I was wanting to blend better, but it should look ok after sanding and shaping. I pull out the index mold and the slot looks rough now, but good. Using a flat needle file, I start shaping the button lip. Without a doubt – in my opinion, button rebuilding is the most time consuming and meticulous aspect of restoring estate pipes. Patiently, I file the button and slot to a shape that is consistent with the original button curvature. Using the lower lip as the template, I shape, file, shape, file…. It’s looking good. Pictures show the progress.

With the main file sculpting done, I use 240 grit sanding paper and sand the button, bit, and slot to blend the patch and the native acrylic. Then, using 600 grit paper I fine tune, then a hearty buffing with 0000 steel wool.

With the main file sculpting done, I use 240 grit sanding paper and sand the button, bit, and slot to blend the patch and the native acrylic. Then, using 600 grit paper I fine tune, then a hearty buffing with 0000 steel wool.

Often when rebuilding a button, the patch material reveals air pockets as the sanding and buffing move toward the final stages. This button was no different. To cover these air pockets, I paint a fine layer of thick CA glue over the lip with a tooth pick. The air pocket pits are filled with the CA glue. I again run over the lip surface with a light 240 grit, then 600 grit papers, then the final 0000 grade steel wool buff to blend.

Often when rebuilding a button, the patch material reveals air pockets as the sanding and buffing move toward the final stages. This button was no different. To cover these air pockets, I paint a fine layer of thick CA glue over the lip with a tooth pick. The air pocket pits are filled with the CA glue. I again run over the lip surface with a light 240 grit, then 600 grit papers, then the final 0000 grade steel wool buff to blend.

With the button repair completed, I move on with the micromesh pad sanding of the acrylic stem. I wet sand using pads 1500 to 2400. I follow this with pads 3200 to 4000 then finish with pads 6000 to 12000. I’m careful to avoid the ‘BC’ stem stamping as I sand. During the sanding, I also sand the white acrylic divider between stem and shank to spruce it up as well. Even though I don’t believe the application of Obsidian Oil helps an acrylic stem, I do it anyway because it looks good and seems to bring out the marbling. I have to admit, the button’s rebuild came out better than expected. Even though I couldn’t create the gray hue in the patch material, the black seems to blend perfectly with the stem. The dubbing of this Butz-Choquin Cadre Noir as being a ‘modern’ pipe, I think fits well with the results – looks great. The pictures show the stem’s progress.

With the button repair completed, I move on with the micromesh pad sanding of the acrylic stem. I wet sand using pads 1500 to 2400. I follow this with pads 3200 to 4000 then finish with pads 6000 to 12000. I’m careful to avoid the ‘BC’ stem stamping as I sand. During the sanding, I also sand the white acrylic divider between stem and shank to spruce it up as well. Even though I don’t believe the application of Obsidian Oil helps an acrylic stem, I do it anyway because it looks good and seems to bring out the marbling. I have to admit, the button’s rebuild came out better than expected. Even though I couldn’t create the gray hue in the patch material, the black seems to blend perfectly with the stem. The dubbing of this Butz-Choquin Cadre Noir as being a ‘modern’ pipe, I think fits well with the results – looks great. The pictures show the stem’s progress.

Next, I look at the BC’s rustified stummel. The dark deep contours of the bubbled rustication make the peaks of the bubbles stand out. I like the Leprechaun look of the pipe. To polish and protect the surface, I use Museum Wax wetted with a bit of spittle, applying it with a cotton cloth. I work the wax into the crooks and crannies of the rustification. After working the Museum Wax into the rustified surface, I do an initial hand buff with a bristled shoe brush. Following this, to deepen the buff and heighten the shine, I mount the Dremel with a cotton cloth buffing wheel set at 40% speed and buff the surface further. Pictures show the progress.

Next, I look at the BC’s rustified stummel. The dark deep contours of the bubbled rustication make the peaks of the bubbles stand out. I like the Leprechaun look of the pipe. To polish and protect the surface, I use Museum Wax wetted with a bit of spittle, applying it with a cotton cloth. I work the wax into the crooks and crannies of the rustification. After working the Museum Wax into the rustified surface, I do an initial hand buff with a bristled shoe brush. Following this, to deepen the buff and heighten the shine, I mount the Dremel with a cotton cloth buffing wheel set at 40% speed and buff the surface further. Pictures show the progress.

Again, picking up the stem, after mounting the Dremel with a cotton cloth wheel for Blue Diamond, I buff the acrylic stem with a high gloss using the compound. Before applying carnauba wax to the stem, I want to freshen the ‘BC’ stamping on the side of the stem. The ‘C’ has grown less distinct. Using white acrylic paint, I apply it over the stamping hoping that there’s enough edge left in the ‘C’ to hold the paint. After it dries, I gently rub off the excess paint using the middle flat edge of a tooth pick. The ‘BC’ is a bit more distinct now. Pictures show the progress.

Again, picking up the stem, after mounting the Dremel with a cotton cloth wheel for Blue Diamond, I buff the acrylic stem with a high gloss using the compound. Before applying carnauba wax to the stem, I want to freshen the ‘BC’ stamping on the side of the stem. The ‘C’ has grown less distinct. Using white acrylic paint, I apply it over the stamping hoping that there’s enough edge left in the ‘C’ to hold the paint. After it dries, I gently rub off the excess paint using the middle flat edge of a tooth pick. The ‘BC’ is a bit more distinct now. Pictures show the progress.

The cotton cloth is mounted on the Dremel and I apply carnauba wax to the acrylic stem at 40% speed. After applying the carnauba over the stem, I reunite the gray marbled acrylic stem with the Leprechaun stummel and give it a good hand buff using a micromesh cloth.

The cotton cloth is mounted on the Dremel and I apply carnauba wax to the acrylic stem at 40% speed. After applying the carnauba over the stem, I reunite the gray marbled acrylic stem with the Leprechaun stummel and give it a good hand buff using a micromesh cloth.