Blog by Steve Laug

The third pipe, #18 of Bob Kerr’s Estate is part of my continuing to change things up a bit with the pipes in the estate. This pipe is a beautiful chubby shanked billiard in Bruyere colour like the Dunhill Bruyere pipes. It was very dirty but there was some beauty underneath the grime and the lava on the rim. I will be going back to Bob’s Dunhill collection eventually. I wanted to continue the change and chubby shank Parker billiard fit the bill for me. It is stamped with the 252 shape number on the left side of the shank at the bowl shank union. Following that it reads Parker Super Bruyere. On the right side of the shank it is stamped Made in London England with a 4 in a circle designating the size of the pipe according to the Dunhill pipe sizes. The stem is tapered with the Diamond P on the top side. The grain and shape on this one is very nice and well worth the time to clean up. I took photos of the pipe before I started my cleanup on it.

The third pipe, #18 of Bob Kerr’s Estate is part of my continuing to change things up a bit with the pipes in the estate. This pipe is a beautiful chubby shanked billiard in Bruyere colour like the Dunhill Bruyere pipes. It was very dirty but there was some beauty underneath the grime and the lava on the rim. I will be going back to Bob’s Dunhill collection eventually. I wanted to continue the change and chubby shank Parker billiard fit the bill for me. It is stamped with the 252 shape number on the left side of the shank at the bowl shank union. Following that it reads Parker Super Bruyere. On the right side of the shank it is stamped Made in London England with a 4 in a circle designating the size of the pipe according to the Dunhill pipe sizes. The stem is tapered with the Diamond P on the top side. The grain and shape on this one is very nice and well worth the time to clean up. I took photos of the pipe before I started my cleanup on it.

I turned to Pipedia to gather some background on the pipe and to see if I could possibly arrive at a date for its crafting (http://www.pipephil.eu/logos/en/logo-parker.html). I quote from that article in part to set the stage for this restoration.

I turned to Pipedia to gather some background on the pipe and to see if I could possibly arrive at a date for its crafting (http://www.pipephil.eu/logos/en/logo-parker.html). I quote from that article in part to set the stage for this restoration.

Parker Pipe Co. was created in 1923 by Dunhill. After Dunhill acquired Hardcastle the two companies were merged (1967) in the Parker-Hardcastle Ltd.

Like Dunhill pipes, Parkers were also date coded but had a independant cycle.

From 1925 through 1941 the date code of Parker pipes runs from 2 to 18.

From 1945 through 1949 the date code runs from 20 to 24.

From 1950 through 1957 (at least) the date suffix run from an underlined and raised 0 to 7.

More recent Parker Super Bruyere did not have the date code.

I turned to Pipedia and did a bit more reading on the brand (https://pipedia.org/wiki/Parker). I quote in part below:

In 1922 the Parker Pipe Co. Limited was formed by Alfred Dunhill to finish and market what Dunhill called its “failings” or what has come to be called by collectors as seconds. Previous to that time, Dunhill marketed its own “failings”, often designated by a large “X” over the typical Dunhill stamping or “Damaged Price” with the reduced price actually stamped on the pipe.

While the timing and exact nature of the early relationship remains a bit of mystery, Parker was destined to eventually merge with Hardcastle when in 1935 Dunhill opened a new pipe factory next door to Hardcastle, and purchased 49% of the company shares in 1936. In 1946, the remaining shares of Hardcastle were obtained, but it was not until 1967 when Parker-Hardcastle Limited was formed.

It is evident through the Dunhill factory stamp logs that Parker and Dunhill were closely linked at the factory level through the 1950s, yet it was much more than a few minor flaws that distinguishing the two brands. Most Dunhill “failings” would have been graded out after the bowl turning process exposed unacceptable flaws. This was prior to stoving, curing, carving, bit work and finishing. In others words, very few Parkers would be subjected to the same rigorous processes and care as pipes destined to become Dunhills. Only those that somehow made it to the end finishing process before becoming “failings” enjoy significant Dunhill characteristics, and this likely represents very few Parker pipes.

After the war, and especially after the mid 1950s the differences between Parker and Dunhill became even more evident, and with the merger of Parker with Hardcastle Pipe Ltd, in 1967 the Parker pipe must be considered as an independent product. There is no record of Parker ever being marketed by Dunhill either in it’s retail catalog or stores.

Parker was a successful pipe in the US market during the 1930s up through the 1950s, at which point it faded from view in the US, while continuing to be popular in the UK. It was re-introduced into the US market in 1991 and is also sold in Europe…

…Prior to Word War II, the possessive PARKER’S stamp was used. However, at least some pipes were stamped with the non-possessive as early as 1936.

Like Dunhill, Parker pipes are date stamped, but differently than Dunhill. The Parker date code always followed the MADE IN LONDON over ENGLAND stamping. The first year’s pipes (1923) had no date code; from 1924 on it ran consecutively from 1 to 19.

There is no indication of a date code for the war years. Parker was not a government approved pipe manufacturer, while Dunhill and Hardcastle were. During the war years Parker manufactured the “Wunup” pipe made of bakelite and clay. A Parker pipe with a 19 date code has been reported, indicating there was perhaps some production of briar pipes as well, but no dating record.

From 1945 through 1949 the Parker date code runs from 20 to 24 and from 1950 through 1957 it runs from an underlined and raised 0 to an underlined and raised 7.

A little help here from anyone with date code information beyond 1957 would be most appreciated.

The site did give me a lot of information about the Parker brand and its connection to Dunhill. I could tell that the pipe that I was working on was made after 1957 as the pipes prior to that time had the date stamp following the D in England.

I took some close up photos of the rim top and the stem to show what I was dealing with. Parker Chubby Billiard was in pretty good condition considering its age and use. The photo shows the cake in the bowl and the thick buildup of lava on the back side of the rim top. You can see the cake in the bowl in the first photo below. The stem was dirty and oxidized with very light tooth chatter on the top and underside for about an inch ahead of the button.  I took a photo of the stamping on both sides of the shank so you can see what it looked like when I examined it. It is clear and readable.

I took a photo of the stamping on both sides of the shank so you can see what it looked like when I examined it. It is clear and readable. With the identification of the pipe as coming out of the Parker/Dunhill factory after 1957 was as good as I was going to get on this old pipe. But that date works well with the other datable pipes in Bob’s collection. I thought it would be good to read about Bob again just to keep his memory alive as you read about his pipes.

With the identification of the pipe as coming out of the Parker/Dunhill factory after 1957 was as good as I was going to get on this old pipe. But that date works well with the other datable pipes in Bob’s collection. I thought it would be good to read about Bob again just to keep his memory alive as you read about his pipes.

I asked his son in law, Brian if he or his wife would like to write a brief biographical tribute to her father, Bob. His daughter wrote the following tribute to her Dad and it really goes well with the belief of rebornpipes that we carry on the trust of the pipe man who first bought the pipe we hold in our hands as we use it and when it is new we hold it in trust for the next person who will enjoy the beauty and functionality of the pipe.

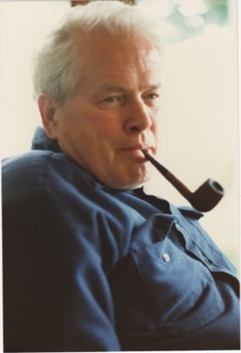

Brian and his wife included the great photo of Bob with a pipe in his mouth. Thank you Bob for the great collection of pipes you provided for me to work on and get out to other pipemen and women who can enjoy them And thank you Brian and your wife for not only this fitting tribute but also for entrusting us with the pipes. Here is his daughter’s tribute to her Dad.

I am delighted to pass on these beloved pipes of my father’s. I hope each user gets many hours of contemplative pleasure as he did. I remember the aroma of tobacco in the rec room, as he put up his feet on his lazy boy. He’d be first at the paper then, no one could touch it before him. Maybe there would be a movie on with an actor smoking a pipe. He would have very definite opinions on whether the performer was a ‘real’ smoker or not, a distinction which I could never see but it would be very clear to him. He worked by day as a sales manager of a paper products company, a job he hated. What he longed for was the life of an artist, so on the weekends and sometimes mid-week evenings he would journey to his workshop and come out with wood sculptures, all of which he declared as crap but every one of them treasured by my sister and myself. Enjoy the pipes, and maybe a little of his creative spirit will enter you!

I am delighted to pass on these beloved pipes of my father’s. I hope each user gets many hours of contemplative pleasure as he did. I remember the aroma of tobacco in the rec room, as he put up his feet on his lazy boy. He’d be first at the paper then, no one could touch it before him. Maybe there would be a movie on with an actor smoking a pipe. He would have very definite opinions on whether the performer was a ‘real’ smoker or not, a distinction which I could never see but it would be very clear to him. He worked by day as a sales manager of a paper products company, a job he hated. What he longed for was the life of an artist, so on the weekends and sometimes mid-week evenings he would journey to his workshop and come out with wood sculptures, all of which he declared as crap but every one of them treasured by my sister and myself. Enjoy the pipes, and maybe a little of his creative spirit will enter you!

I reamed the bowl to remove the cake on the walls and the debris that still remained in the bowl. I used a PipNet pipe reamer to start the process. I followed that with a Savinelli Fitsall Pipe Knife to clean up the remaining cake in the U-shaped bottom of the bowl. I sanded the bowl with 220 grit sandpaper wrapped around a piece of dowel. It smooths out the walls and also helps deal with slight damage to the inner edges of the bowl.

I cleaned up the rim top and removed the thick lava coat on the back top side of the rim. I used a pen knife blade the edge of the Savinelli Fitsall knife to scrape away the high spots of lava. I used a Scotch-Brite sponge pad to scrub off the remaining lava on the top of the bowl and wiped it down with a bit of saliva on a cotton pad.

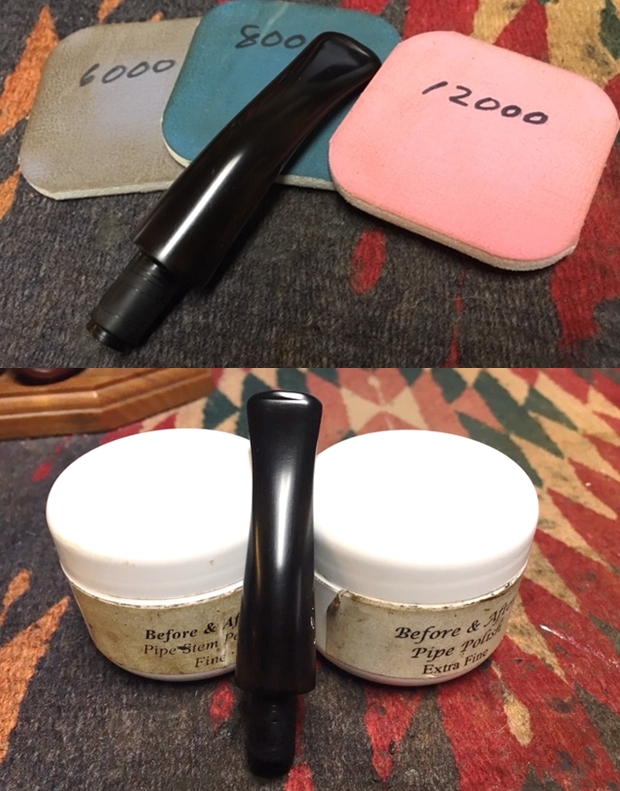

I cleaned up the rim top and removed the thick lava coat on the back top side of the rim. I used a pen knife blade the edge of the Savinelli Fitsall knife to scrape away the high spots of lava. I used a Scotch-Brite sponge pad to scrub off the remaining lava on the top of the bowl and wiped it down with a bit of saliva on a cotton pad. I polished the rim top with micromesh sanding pads – wet sanding with 1500-2400 grit pads and dry sanding with 3200-12000 grit pads. Each successive pad brought more shine to the rim top. I wiped the rim down with a damp cotton pad after each sanding pad. The shine develops through the polishing.

I polished the rim top with micromesh sanding pads – wet sanding with 1500-2400 grit pads and dry sanding with 3200-12000 grit pads. Each successive pad brought more shine to the rim top. I wiped the rim down with a damp cotton pad after each sanding pad. The shine develops through the polishing.

With the removal of the lava coat and polishing of the rim it lightened significantly. I used a Maple and a Mahagony stain pen to blend the colours to match the colour of the rest of the bowl. I would buff it and blend it in better once the stain dried.

With the removal of the lava coat and polishing of the rim it lightened significantly. I used a Maple and a Mahagony stain pen to blend the colours to match the colour of the rest of the bowl. I would buff it and blend it in better once the stain dried. I worked some Before & After Restoration Balm into the finish of the bowl and shank as well as the surface of the rim top. I worked it into the surface with my fingertips to clean, enliven and protect the wood. I let the balm sit for about 20 minutes and buffed it off with a soft cotton cloth to polish the bowl. I took photos of the pipe at this point in the process to show what the bowl looked like at this point.

I worked some Before & After Restoration Balm into the finish of the bowl and shank as well as the surface of the rim top. I worked it into the surface with my fingertips to clean, enliven and protect the wood. I let the balm sit for about 20 minutes and buffed it off with a soft cotton cloth to polish the bowl. I took photos of the pipe at this point in the process to show what the bowl looked like at this point.

I cleaned out the internals of the bowl, shank and the airway in the shank and the stem with alcohol, pipe cleaners and cotton swabs until they came out clean.

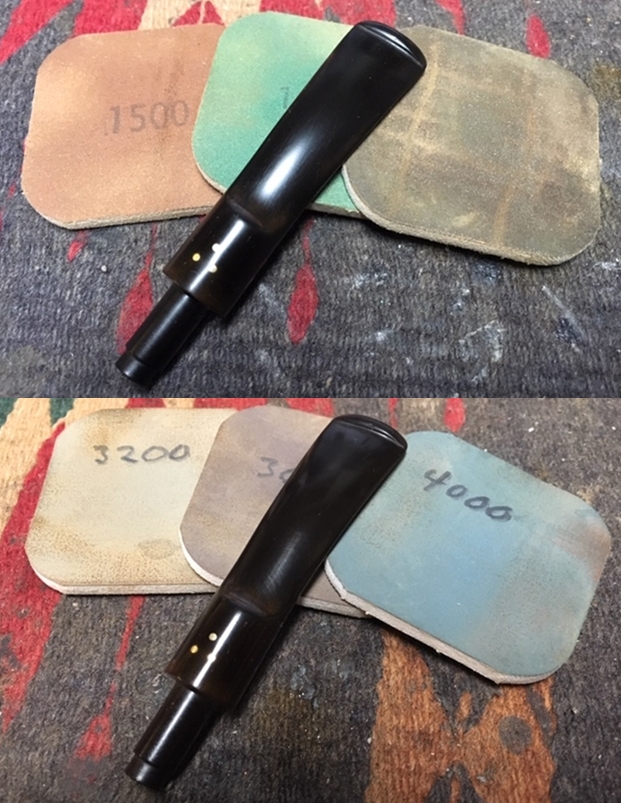

I cleaned out the internals of the bowl, shank and the airway in the shank and the stem with alcohol, pipe cleaners and cotton swabs until they came out clean.  I set the bowl aside and turned my attention to the stem. I sanded out the light tooth chatter on the surface of the vulcanite with a folded piece of 220 grit sandpaper and worked on the spotted oxidation on the surface. I followed the 220 grit sandpaper with 400 grit wet dry sandpaper to minimize the scratching. The two papers combined did a pretty decent job of getting rid of the tooth marks and chatter as well as the oxidation.

I set the bowl aside and turned my attention to the stem. I sanded out the light tooth chatter on the surface of the vulcanite with a folded piece of 220 grit sandpaper and worked on the spotted oxidation on the surface. I followed the 220 grit sandpaper with 400 grit wet dry sandpaper to minimize the scratching. The two papers combined did a pretty decent job of getting rid of the tooth marks and chatter as well as the oxidation. I polished the stem with Denicare Mouthpiece Polish to take out the oxidation at the button edge and on the end of the mouthpiece. I also worked hard to scrub it from the surface of the stem at the tenon end.

I polished the stem with Denicare Mouthpiece Polish to take out the oxidation at the button edge and on the end of the mouthpiece. I also worked hard to scrub it from the surface of the stem at the tenon end. I applied some Rub’n Buff Antique Gold to the Diamond P stamping on the topside of the stem. The original Diamond P stamp was gold. I applied it with a pipe cleaner and then buffed it off with a cotton pad. The repaired stamping looked really good.

I applied some Rub’n Buff Antique Gold to the Diamond P stamping on the topside of the stem. The original Diamond P stamp was gold. I applied it with a pipe cleaner and then buffed it off with a cotton pad. The repaired stamping looked really good. I polished out the scratches with micromesh sanding pads – wet sanding with 1500-2400 grit pads and dry sanding with 3200-12000 grit pads. I wiped the stem down after each sanding pad with Obsidian Oil. I polished it with Before & After Pipe Stem Polish – both Fine and Extra Fine. Once I had finished the polishing I gave it a final coat of oil and set it aside to dry.

I polished out the scratches with micromesh sanding pads – wet sanding with 1500-2400 grit pads and dry sanding with 3200-12000 grit pads. I wiped the stem down after each sanding pad with Obsidian Oil. I polished it with Before & After Pipe Stem Polish – both Fine and Extra Fine. Once I had finished the polishing I gave it a final coat of oil and set it aside to dry.

I put the bowl and stem back together. I buffed the bowl and stem with Blue Diamond to polish out the scratches in the briar and the vulcanite. I gave the bowl and the stem multiple coats of carnauba wax. I buffed the pipe with a clean buffing pad to raise the shine. I hand buffed it with a microfiber cloth to deepen the shine. The pipe polished up pretty nicely. The smooth finish on this Parker Super Bruyere is very nice almost equal to its match in the Dunhill Line. The only flaw I can see is a tiny sandpit in the outer edge of the bowl toward the back. It is quite beautiful and it has some amazing grain around the bowl – a mix of cross grain, birdseye and flame. The contrast of swirling grain looked good with the polished black vulcanite. This Parker will soon be heading off to India to join Paresh’s rotation. The finished pipe is shown in the photos below. The dimensions of the pipe are Length: 5 3/4 inches, Height: 1 7/8 inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 1/4 inches, Chamber diameter: 3/4 of an inch. This is the 18th pipe from the many pipes that will be coming onto the work table from the Bob’s estate. There are a lot more pipes to work on from the Estate so keep an eye on the blog to see forthcoming restorations. Thanks for reading this blog and my reflections on the pipe while I worked on it. I am having fun working on this estate.

I put the bowl and stem back together. I buffed the bowl and stem with Blue Diamond to polish out the scratches in the briar and the vulcanite. I gave the bowl and the stem multiple coats of carnauba wax. I buffed the pipe with a clean buffing pad to raise the shine. I hand buffed it with a microfiber cloth to deepen the shine. The pipe polished up pretty nicely. The smooth finish on this Parker Super Bruyere is very nice almost equal to its match in the Dunhill Line. The only flaw I can see is a tiny sandpit in the outer edge of the bowl toward the back. It is quite beautiful and it has some amazing grain around the bowl – a mix of cross grain, birdseye and flame. The contrast of swirling grain looked good with the polished black vulcanite. This Parker will soon be heading off to India to join Paresh’s rotation. The finished pipe is shown in the photos below. The dimensions of the pipe are Length: 5 3/4 inches, Height: 1 7/8 inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 1/4 inches, Chamber diameter: 3/4 of an inch. This is the 18th pipe from the many pipes that will be coming onto the work table from the Bob’s estate. There are a lot more pipes to work on from the Estate so keep an eye on the blog to see forthcoming restorations. Thanks for reading this blog and my reflections on the pipe while I worked on it. I am having fun working on this estate.