by Kenneth Lieblich

I’ve had this pipe in my stash for a long time, and I don’t really remember acquiring it. I always thought it was a neat shape and just required the right moment for restoration. Well, the pipe found its way back into my hand and the time for restoration has come. This is a Ben Wade Standard 53 skater and it has seen better days. The pipe is worn, dirty, and tired-looking. There is some stunning grain under the grime and it holds a real charm. I’m sure you will be charmed!

Here are the markings on the pipe. On the left side of the shank, we see Ben Wade [over] Standard [over] London England. On the right side, we see the shape number 53. Meanwhile, on the top of the stem, we see the words Ben [over] Wade. Doing some elementary research and comparing styles of nomenclature, this pipe looks to me as though it could be from the ‘post-family, pre-Lane’ era of Ben Wade, but I am not sure. Based on what Steve told me, it also seems possible that this Ben Wade comes from the Charatan era. The skater was a well-known Charatan shape. I suppose that shape number 53 is probably a Ben Wade number, rather than a Charatan one. I am, naturally, inclined to trust Steve’s judgment over my own on this.

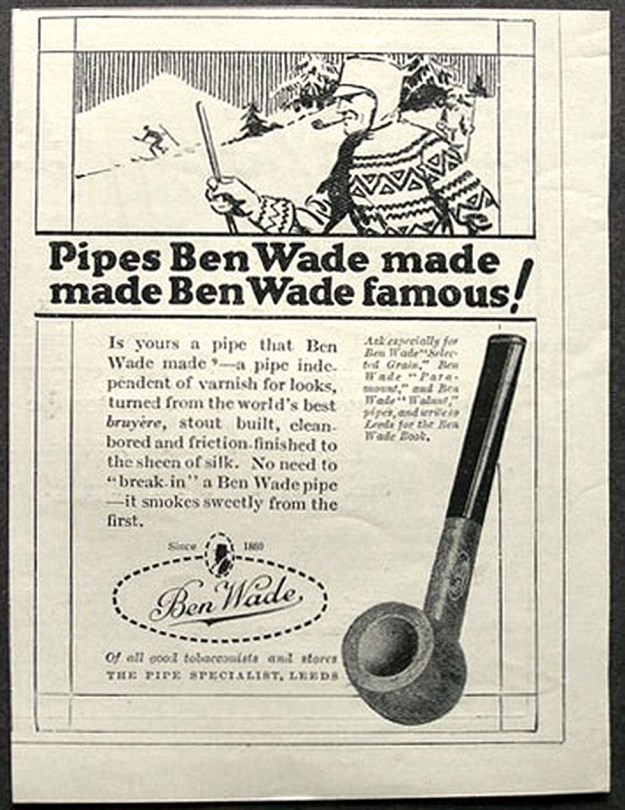

Here are the markings on the pipe. On the left side of the shank, we see Ben Wade [over] Standard [over] London England. On the right side, we see the shape number 53. Meanwhile, on the top of the stem, we see the words Ben [over] Wade. Doing some elementary research and comparing styles of nomenclature, this pipe looks to me as though it could be from the ‘post-family, pre-Lane’ era of Ben Wade, but I am not sure. Based on what Steve told me, it also seems possible that this Ben Wade comes from the Charatan era. The skater was a well-known Charatan shape. I suppose that shape number 53 is probably a Ben Wade number, rather than a Charatan one. I am, naturally, inclined to trust Steve’s judgment over my own on this. Pipedia has a good write-up on Ben Wade and I encourage you to read it here. This is a little snippet of the article:

Pipedia has a good write-up on Ben Wade and I encourage you to read it here. This is a little snippet of the article:

Ben Wade is one of the great names in English pipe making. As Richard Carleton Hacker noticed correctly Ben Wade, like many British pipe companies, has had a checkered history. Very checkered in this case. The company was founded by Benjamin Wade in 1860 in Leeds, Yorkshire, where it was located for over a century. Ben Wade started as a pipe trader, but yet in the 1860’s he established a workshop to produce briar pipes. The pipes were made in very many standard shapes – always extensively classic and “very British”. Many models tended to be of smaller dimensions. Ben Wade offered a very high standard of craftsmanship and quality without any fills. Thus the pipes were considered to be high grade and a major competitor to other famous English brands. The often heard comparison to Charatan seems to be a little bit inadequate because those days’ Charatans were entirely handmade. Let’s examine the condition. First and foremost, this pipe is really dirty. There’s lots of filth matted everywhere – especially the rim. There wasn’t much damage to the briar to be seen initially – although that would change once cleaning began. Having said that, there were a few small nicks in the briar. The smoking chamber had plenty of cake and looked like it would take some hard work to clean up. The stem was coated in oxidation and calcification. It was very dirty too and had a few tooth dents. In short, I had my work cut out for me.

Let’s examine the condition. First and foremost, this pipe is really dirty. There’s lots of filth matted everywhere – especially the rim. There wasn’t much damage to the briar to be seen initially – although that would change once cleaning began. Having said that, there were a few small nicks in the briar. The smoking chamber had plenty of cake and looked like it would take some hard work to clean up. The stem was coated in oxidation and calcification. It was very dirty too and had a few tooth dents. In short, I had my work cut out for me.

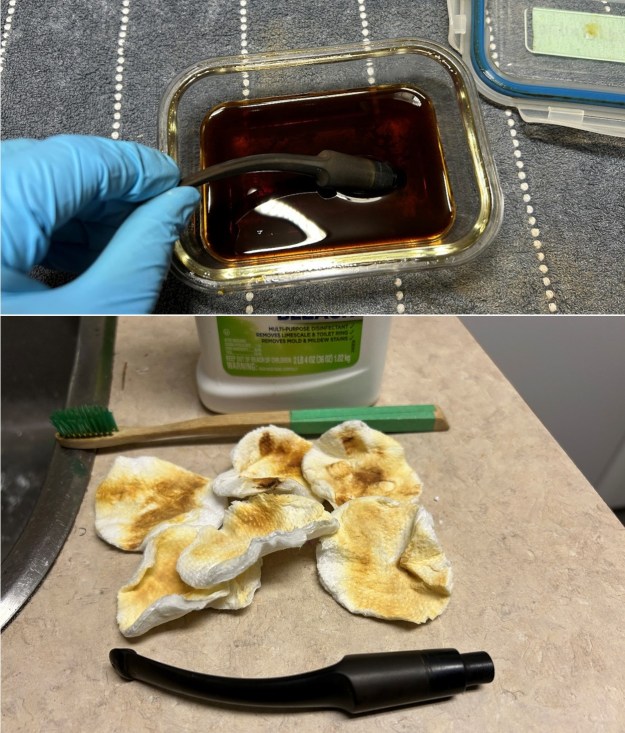

The stem’s calcification was quite substantial. I used an old butter knife and gently scraped some of the thicker accretion off. Doing this now helps later in removing the oxidation. I then used alcohol on a few cotton rounds and wiped down the stem to provide an initial cleaning of filth before moving on to the next steps. The primary cleaning came next. I disinfected the inside of the stem with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. I scrubbed thoroughly to make sure the interior was very clean. This stem is so dirty. I used a LOT of pipe cleaners and cotton swabs.

The stem’s calcification was quite substantial. I used an old butter knife and gently scraped some of the thicker accretion off. Doing this now helps later in removing the oxidation. I then used alcohol on a few cotton rounds and wiped down the stem to provide an initial cleaning of filth before moving on to the next steps. The primary cleaning came next. I disinfected the inside of the stem with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. I scrubbed thoroughly to make sure the interior was very clean. This stem is so dirty. I used a LOT of pipe cleaners and cotton swabs. The goal of the next step is the removal (or minimization) of oxidation. Going to my sink, I used cream cleanser, cotton rounds, and a toothbrush, and scoured the stem to remove as much surface oxidation as possible. As the photos show, the result was a hideous, brownish mess – but better off the stem than on it.

The goal of the next step is the removal (or minimization) of oxidation. Going to my sink, I used cream cleanser, cotton rounds, and a toothbrush, and scoured the stem to remove as much surface oxidation as possible. As the photos show, the result was a hideous, brownish mess – but better off the stem than on it. Once the stem was reasonably clean, I soaked it overnight in some Briarville Stem Oxidation Remover. This solution works to draw oxidation in the stem to the surface of the vulcanite. This is a major aid and an important step in ensuring a clean stem. The following day, I drew out the stem from its bath and scrubbed the lingering fluid with a toothbrush. Due to the severity of the oxidation, I then repeated the scrubbing with the cream cleanser for maximum effect.

Once the stem was reasonably clean, I soaked it overnight in some Briarville Stem Oxidation Remover. This solution works to draw oxidation in the stem to the surface of the vulcanite. This is a major aid and an important step in ensuring a clean stem. The following day, I drew out the stem from its bath and scrubbed the lingering fluid with a toothbrush. Due to the severity of the oxidation, I then repeated the scrubbing with the cream cleanser for maximum effect. As the stem was now clean and dry, I set about fixing the marks and dents in the vulcanite. This was done by filling those divots with black cyanoacrylate adhesive, impregnated with carbon and rubber. I left this to cure and moved on. After this, I painted the logo on the stem with some enamel nail polish. I restored the logo carefully and let it fully set before proceeding.

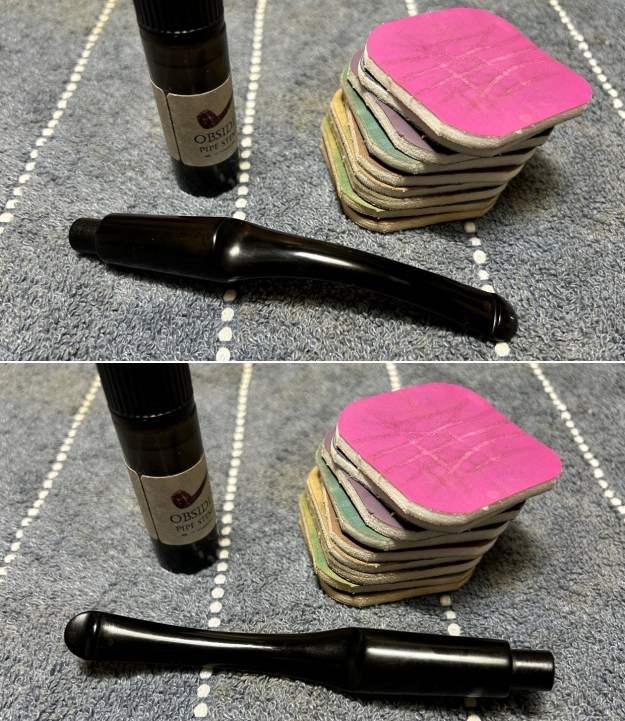

As the stem was now clean and dry, I set about fixing the marks and dents in the vulcanite. This was done by filling those divots with black cyanoacrylate adhesive, impregnated with carbon and rubber. I left this to cure and moved on. After this, I painted the logo on the stem with some enamel nail polish. I restored the logo carefully and let it fully set before proceeding. The penultimate step for the stem is sanding. First, with my set of needle files, I reduced the bulk of the cyanoacrylate repairs. I removed the excess adhesive as near to the surface as possible, without cutting into the vulcanite. Following that, I used all nine of the micromesh sanding pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand out flaws, even out the vulcanite, and provide gentle polishing of the finished surface. I also applied pipe-stem oil while using the last five micromesh pads. There was a wonderful, deep black shine to the stem when I was done.

The penultimate step for the stem is sanding. First, with my set of needle files, I reduced the bulk of the cyanoacrylate repairs. I removed the excess adhesive as near to the surface as possible, without cutting into the vulcanite. Following that, I used all nine of the micromesh sanding pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand out flaws, even out the vulcanite, and provide gentle polishing of the finished surface. I also applied pipe-stem oil while using the last five micromesh pads. There was a wonderful, deep black shine to the stem when I was done. As the stem was (nearly) complete, I moved on to the stummel. The first step was to ream out the bowl – that is to say, remove all the cake inside the bowl. This accomplished a couple of things. First (and most obviously), it cleaned the bowl and provided a refurbished chamber for future smoking. Second, when the old cake was removed, I could inspect the interior walls of the bowl and determine if there was damage or not. I used a reamer, a pipe knife, and a piece of sandpaper taped to a wooden dowel. Collectively, these ensured that all the debris was removed.

As the stem was (nearly) complete, I moved on to the stummel. The first step was to ream out the bowl – that is to say, remove all the cake inside the bowl. This accomplished a couple of things. First (and most obviously), it cleaned the bowl and provided a refurbished chamber for future smoking. Second, when the old cake was removed, I could inspect the interior walls of the bowl and determine if there was damage or not. I used a reamer, a pipe knife, and a piece of sandpaper taped to a wooden dowel. Collectively, these ensured that all the debris was removed. My next step was to remove the lava on the rim. For this, I took a piece of machine steel and gently scraped the lava away. The metal’s edge is sharp enough to remove what I need, but not so sharp that it damages the rim. This work revealed some serious damage to the rim. It was badly scraped and I would need to address that.

My next step was to remove the lava on the rim. For this, I took a piece of machine steel and gently scraped the lava away. The metal’s edge is sharp enough to remove what I need, but not so sharp that it damages the rim. This work revealed some serious damage to the rim. It was badly scraped and I would need to address that. The inside of the stummel needed to be cleaned thoroughly. However, this pipe was so clogged, that I first needed to open the horribly occluded airway. So, I took a long drill bit and hand-cranked it to dislodge the dreadful detritus inside. Hand cranking is essential because it provides a precision and caution that a power drill cannot provide. Similar to the stem, I then cleaned the stummel with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. This stummel was sooooo dirty. It took ages and much cotton to get clean – much more than is shown in the photo.

The inside of the stummel needed to be cleaned thoroughly. However, this pipe was so clogged, that I first needed to open the horribly occluded airway. So, I took a long drill bit and hand-cranked it to dislodge the dreadful detritus inside. Hand cranking is essential because it provides a precision and caution that a power drill cannot provide. Similar to the stem, I then cleaned the stummel with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. This stummel was sooooo dirty. It took ages and much cotton to get clean – much more than is shown in the photo. I then decided to ‘de-ghost’ the pipe – that is to say, exorcize the remaining filth from the briar. I filled the bowl and the shank with cotton balls, then saturated them with 99% isopropyl alcohol. I let the stummel sit overnight. This caused the remaining oils, tars and smells to leach out into the cotton.

I then decided to ‘de-ghost’ the pipe – that is to say, exorcize the remaining filth from the briar. I filled the bowl and the shank with cotton balls, then saturated them with 99% isopropyl alcohol. I let the stummel sit overnight. This caused the remaining oils, tars and smells to leach out into the cotton. To tidy up the briar, I also wiped down the outside with some oil soap on cotton rounds. This did a good job of cleaning any latent dirt on the surface of the briar. The last step of the cleaning process was to scour the inside of the stummel with some soap and tube brushes. This was the culmination of a lot of hard work in getting the pipe clean.

To tidy up the briar, I also wiped down the outside with some oil soap on cotton rounds. This did a good job of cleaning any latent dirt on the surface of the briar. The last step of the cleaning process was to scour the inside of the stummel with some soap and tube brushes. This was the culmination of a lot of hard work in getting the pipe clean. Having completed that, I was able to address the nicks on the bowl. I dug out my iron and a damp cotton flannel cloth. By laying the cloth over the affected areas and applying the iron to it, the hot and moist steam can cause the wood to swell slightly and return to shape. There was some improvement – not a lot, but it was better than doing nothing.

Having completed that, I was able to address the nicks on the bowl. I dug out my iron and a damp cotton flannel cloth. By laying the cloth over the affected areas and applying the iron to it, the hot and moist steam can cause the wood to swell slightly and return to shape. There was some improvement – not a lot, but it was better than doing nothing.  The damage to the rim was significant. In order to lessen the scrapes on the rim, I ‘topped’ the pipe – that is to say, I gently and evenly sanded the rim on a piece of 220-grit sandpaper. This effectively minimized the damage, without altering the look of the pipe. Some damage will always remain and that is fine – it’s part of this pipe’s history.

The damage to the rim was significant. In order to lessen the scrapes on the rim, I ‘topped’ the pipe – that is to say, I gently and evenly sanded the rim on a piece of 220-grit sandpaper. This effectively minimized the damage, without altering the look of the pipe. Some damage will always remain and that is fine – it’s part of this pipe’s history.

I used all nine micromesh pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand the outside of the stummel and finish it off. This sanding minimizes flaws in the briar and provides a beautiful smoothness to the wood. I rubbed some LBE Before & After Restoration Balm into the briar and let it sit for 30 minutes or so. The balm moisturizes the wood and gives a beautiful depth to the briar. I then buffed the stummel with a microfibre cloth.

I used all nine micromesh pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand the outside of the stummel and finish it off. This sanding minimizes flaws in the briar and provides a beautiful smoothness to the wood. I rubbed some LBE Before & After Restoration Balm into the briar and let it sit for 30 minutes or so. The balm moisturizes the wood and gives a beautiful depth to the briar. I then buffed the stummel with a microfibre cloth.

For the final step, I took the pipe to my bench polisher and carefully buffed it – first with a blue diamond compound, then with three coats of carnauba wax. This procedure makes the pipe look its best – the stummel sings and the stem glows.

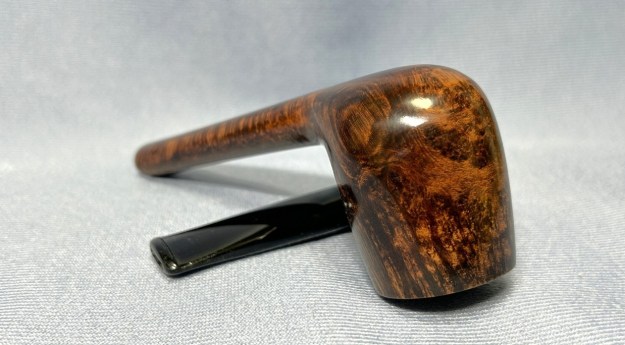

For the final step, I took the pipe to my bench polisher and carefully buffed it – first with a blue diamond compound, then with three coats of carnauba wax. This procedure makes the pipe look its best – the stummel sings and the stem glows. This Ben Wade Standard 53 skater looks fantastic again and is ready to be enjoyed by its next owner. I am pleased to announce that this pipe is for sale! If you are interested in acquiring it for your collection, please have a look in the ‘British’ pipe section of the store here on Steve’s website. You can also email me directly at kenneth@knightsofthepipe.com. The approximate dimensions of the pipe are as follows: length 6 in. (153 mm); height 1⅝ in. (41 mm); bowl diameter 1½ in. (39 mm); chamber diameter ⅞ in. (22 mm). The weight of the pipe is 1¼ oz. (38 g). I hope you enjoyed reading the story of this pipe’s restoration as much as I did restoring it. If you are interested in more of my work, please follow me here on Steve’s website or send me an email. Thank you very much for reading and, as always, I welcome and encourage your comments.

This Ben Wade Standard 53 skater looks fantastic again and is ready to be enjoyed by its next owner. I am pleased to announce that this pipe is for sale! If you are interested in acquiring it for your collection, please have a look in the ‘British’ pipe section of the store here on Steve’s website. You can also email me directly at kenneth@knightsofthepipe.com. The approximate dimensions of the pipe are as follows: length 6 in. (153 mm); height 1⅝ in. (41 mm); bowl diameter 1½ in. (39 mm); chamber diameter ⅞ in. (22 mm). The weight of the pipe is 1¼ oz. (38 g). I hope you enjoyed reading the story of this pipe’s restoration as much as I did restoring it. If you are interested in more of my work, please follow me here on Steve’s website or send me an email. Thank you very much for reading and, as always, I welcome and encourage your comments.