by Steve Laug

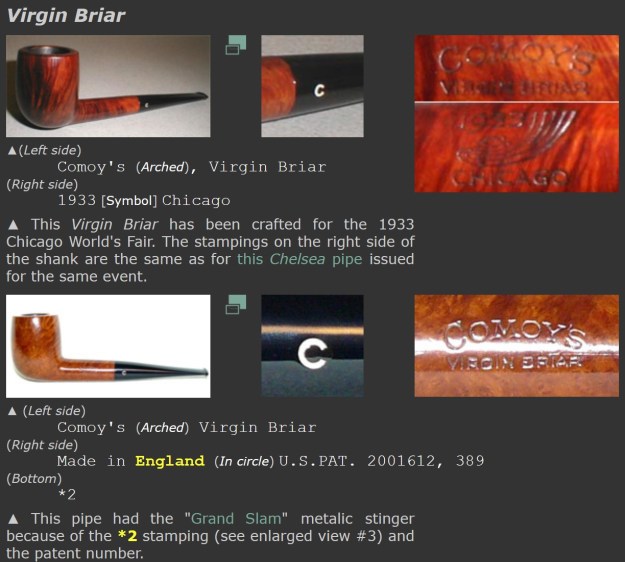

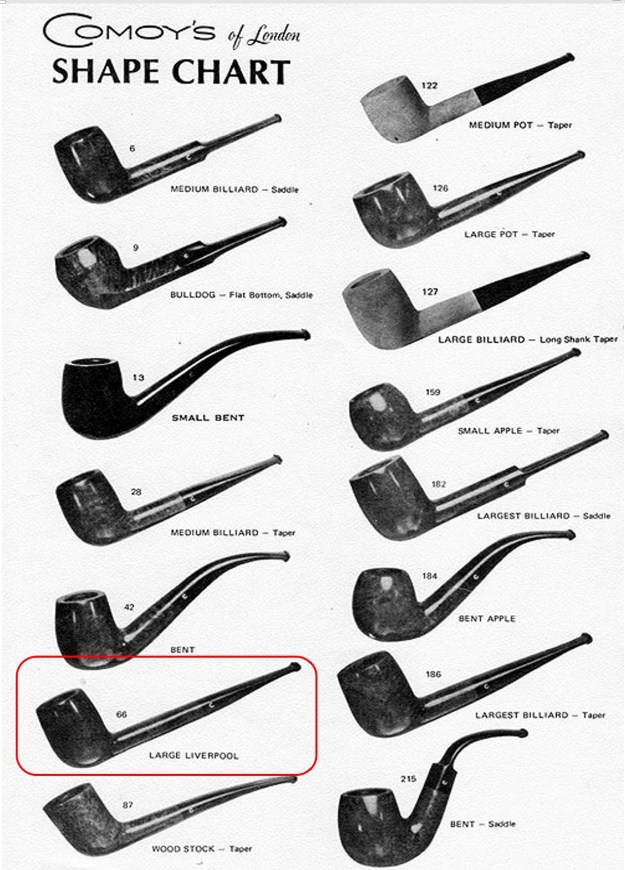

The next pipe on the work table was a Bent Briar Comoy’s Bent Billiard. It came to us from a seller in Downey, California, USA on 08/12/2025. The pipe is stamped Comoy’s [over] Facet on the left side of the shank. On the right side it is stamped with a circular COM stamp that read Made in London in a circle [over] England [over] the shape number 215. The bowl had a thick cake in it that had overflowed as thick lava onto the rim top. The finish was dirty and had tars and oils ground into the finish. There was a triple layer shank brass band – two faceted bands sandwiching a smooth band. The vulcanite stem was oxidized, calcified but the stem only had light tooth chatter on both sides. The C logo was not the three part older logo that was on earlier Comoy’s pipe but rather a one part inlay with a different style font. Jeff took photos of the pipe before he began the cleanup process.

He took photos of the rim top and both sides of the stem to show the condition of both. The close up of the rim top shows the cake in the bowl and the overflow of lava on the rim top and inner edge of the bowl. The stem was oxidized, calcified and both sides of the stem had light tooth chatter near the button.

He took photos of the rim top and both sides of the stem to show the condition of both. The close up of the rim top shows the cake in the bowl and the overflow of lava on the rim top and inner edge of the bowl. The stem was oxidized, calcified and both sides of the stem had light tooth chatter near the button.

The photos of the sides and heel of the bowl show the dirty finish on the sides of the bowl and shank. The briar is quite nice all around the pipe. The finish makes the grain really stand out on the bowl and shank.

The photos of the sides and heel of the bowl show the dirty finish on the sides of the bowl and shank. The briar is quite nice all around the pipe. The finish makes the grain really stand out on the bowl and shank.

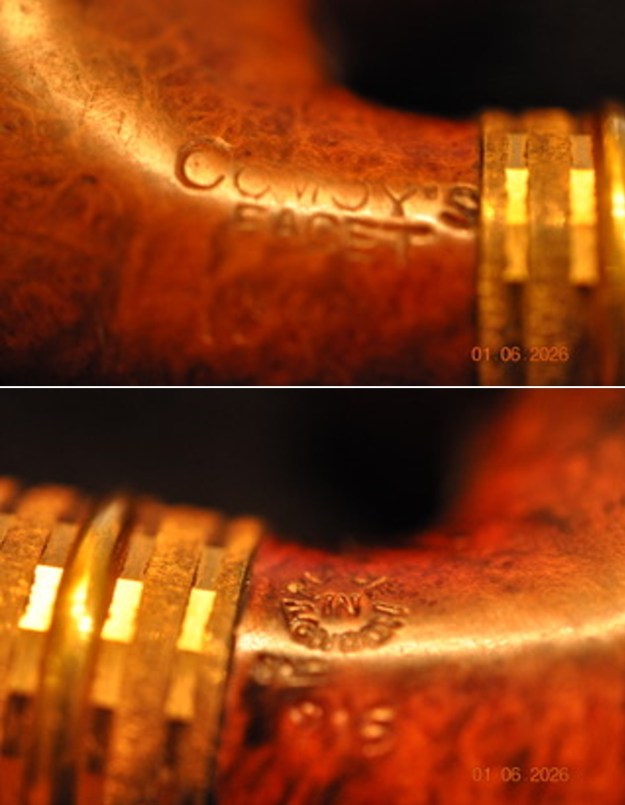

Jeff took a series of photos on the sides of the shank rolling it between photos to make sure that all of the stamping was readable.

Jeff took a series of photos on the sides of the shank rolling it between photos to make sure that all of the stamping was readable.

Jeff had cleaned up the pipe using his usual procedure. He reamed it with a PipNet reamer to remove the heavy cake. He cleaned up the sides of the bowl with a Savinelli Fitsall Pipe Knife. He scrubbed the bowl with undiluted Murphy’s Oil Soap with a tooth brush. He rinsed it under running warm water to remove the soap and grime from around the bowl sides. It looked better but the rim top and inner edge was darkened. The front outer edge showed damage. He cleaned out the inside of the shank and the airway with alcohol, cotton swabs and pipe cleaners. The stem looked good and the light tooth marks on both sides were still visible and would need a little work. I took photos of the pipe once I received it.

Jeff had cleaned up the pipe using his usual procedure. He reamed it with a PipNet reamer to remove the heavy cake. He cleaned up the sides of the bowl with a Savinelli Fitsall Pipe Knife. He scrubbed the bowl with undiluted Murphy’s Oil Soap with a tooth brush. He rinsed it under running warm water to remove the soap and grime from around the bowl sides. It looked better but the rim top and inner edge was darkened. The front outer edge showed damage. He cleaned out the inside of the shank and the airway with alcohol, cotton swabs and pipe cleaners. The stem looked good and the light tooth marks on both sides were still visible and would need a little work. I took photos of the pipe once I received it.

I took a photo of the rim top and the stem to show their condition. Jeff was able to clean up the darkening on the rim that was shown in the rim and bowl photos above. The rim top and outer edge show damage. The stem looked better, though there were some light tooth marks and chatter on both sides ahead of the button.

I took a photo of the rim top and the stem to show their condition. Jeff was able to clean up the darkening on the rim that was shown in the rim and bowl photos above. The rim top and outer edge show damage. The stem looked better, though there were some light tooth marks and chatter on both sides ahead of the button. I took photos of the stamping on the sides of the shank and the band. You can see that it is stamped as noted above. It is faint in spots but still readable. I took the pipe apart and took a photo of the pipe. It is a good-looking pipe and has a rugged rustication around the bowl.

I took photos of the stamping on the sides of the shank and the band. You can see that it is stamped as noted above. It is faint in spots but still readable. I took the pipe apart and took a photo of the pipe. It is a good-looking pipe and has a rugged rustication around the bowl.

I started my work on the bowl by working to minimize the damage on the front outer edge and rim top I worked on them with a folded piece of 220 grit sandpaper. I wanted to smooth out the damaged areas without changing the bowl’s profile. I think it worked well.

I started my work on the bowl by working to minimize the damage on the front outer edge and rim top I worked on them with a folded piece of 220 grit sandpaper. I wanted to smooth out the damaged areas without changing the bowl’s profile. I think it worked well. I sanded the bowl with 320-3500 grit sanding pads to remove the surface scratches in the finish. I carefully avoided the stamping so as not to damage it. I wiped the bowl down with a damp cloth after each pad to remove the sanding debris. The briar began to have a rich shine and the stain on the bowl looked very good.

I sanded the bowl with 320-3500 grit sanding pads to remove the surface scratches in the finish. I carefully avoided the stamping so as not to damage it. I wiped the bowl down with a damp cloth after each pad to remove the sanding debris. The briar began to have a rich shine and the stain on the bowl looked very good.

I polished the bowl sides and the smooth rim top with micromesh sanding pads. I dry sanded it with 1500-12000 grit micromesh pads. I wiped it down after each pad. It really began to be beautiful.

I polished the bowl sides and the smooth rim top with micromesh sanding pads. I dry sanded it with 1500-12000 grit micromesh pads. I wiped it down after each pad. It really began to be beautiful.

I rubbed the bowl and shank down with Before & After Restoration Balm to deep clean the finish on the bowl and shank. The product works to clean, enliven and protect the briar. I worked it in with my fingers to get it into the briar. I let it sit for 10 minutes then I wiped it off and buffed it with a soft cloth. The briar really began to have a rich shine. I took some photos of the bowl at this point to mark the progress in the restoration. It is a beautiful bowl.

I rubbed the bowl and shank down with Before & After Restoration Balm to deep clean the finish on the bowl and shank. The product works to clean, enliven and protect the briar. I worked it in with my fingers to get it into the briar. I let it sit for 10 minutes then I wiped it off and buffed it with a soft cloth. The briar really began to have a rich shine. I took some photos of the bowl at this point to mark the progress in the restoration. It is a beautiful bowl.

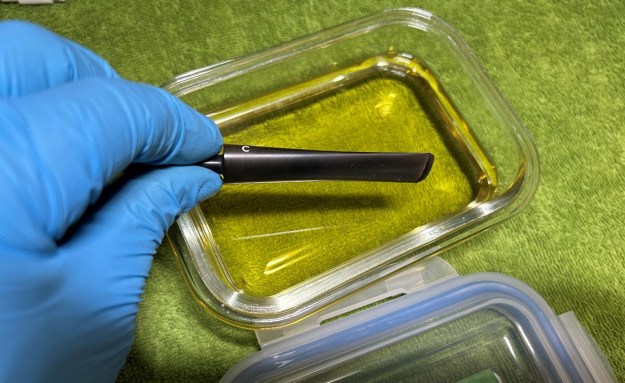

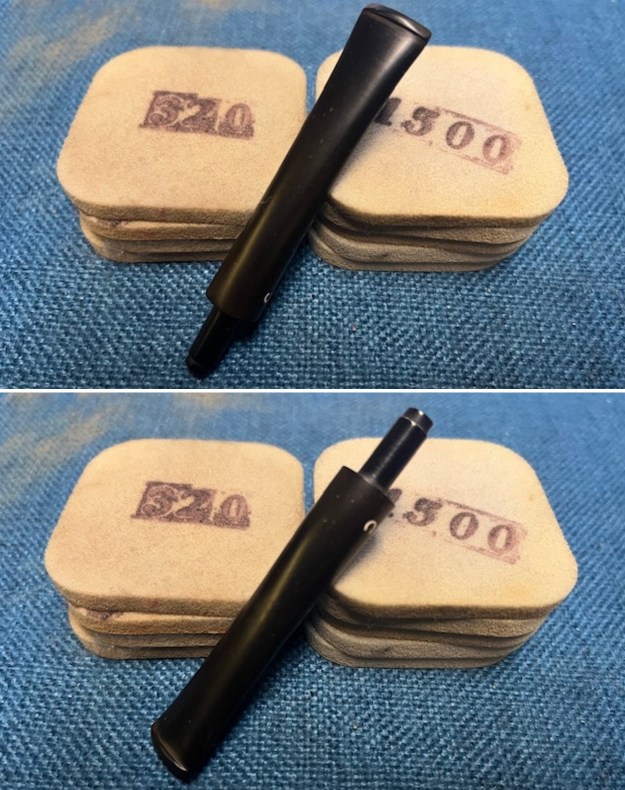

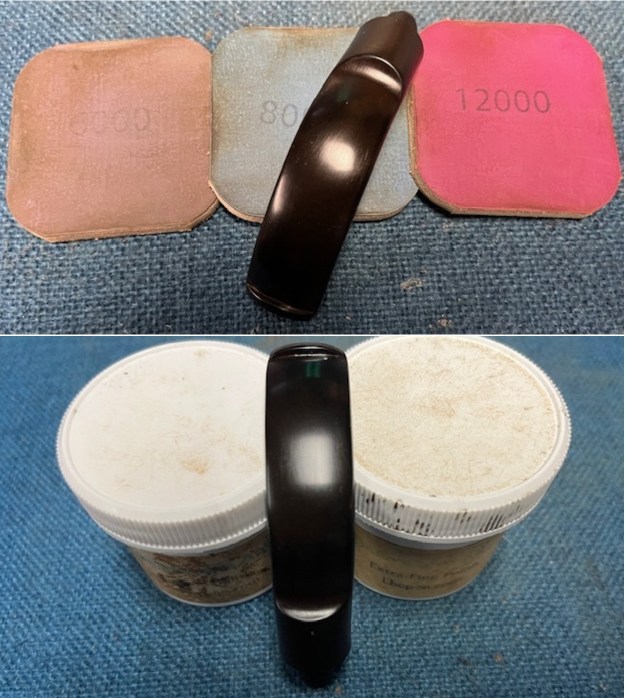

I sanded the stem with the 2 inch square 320-3500 grit sanding pads to remove the light tooth chatter and marks in the acrylic. I wiped down the stem after each sanding pad with Obsidian Oil. I was able to remove the marks and the stem looked very good.

I sanded the stem with the 2 inch square 320-3500 grit sanding pads to remove the light tooth chatter and marks in the acrylic. I wiped down the stem after each sanding pad with Obsidian Oil. I was able to remove the marks and the stem looked very good. I polished the stem with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding with 1500-12000 grit pads. I wiped the stem down after each sanding pad with Obsidian Oil. I did a final hand polish of the stem with Before & After Pipe Stem Polish – both Fine and Extra Fine. I gave it a final wiped down with the cloth and set it aside to dry.

I polished the stem with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding with 1500-12000 grit pads. I wiped the stem down after each sanding pad with Obsidian Oil. I did a final hand polish of the stem with Before & After Pipe Stem Polish – both Fine and Extra Fine. I gave it a final wiped down with the cloth and set it aside to dry.

I put the stem back on the Comoy’s Facet 215 Smooth Bent Billiard and took it to the buffer. I buffed the bowl and stem with Blue Diamond to polish the briar and the vulcanite. Blue Diamond does a great job on the smaller scratches that remain in both. I gave the bowl and the stem several coats of carnauba wax and buffed the pipe with a clean buffing pad to raise the shine. I hand buffed it with a microfiber cloth to deepen the shine. I am amazed at how well it turned out. The finished pipe is shown in the photos below. This is beautiful smooth finished Comoy’s Facet 215 Bent Billiard with brass faceted bands and the vulcanite saddle stem combine to give the pipe a great look. The dimensions of the pipe are Length: 5 inches, Height: 1 ¾ inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 ¼ inches, Chamber diameter: ¾ of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 2.05 ounces/59 grams. This is another pipe that I will be putting on the rebornpipes online store in the British Pipe Makers Section shortly, if you are interested in adding it to your collection. Thanks for walking through the restoration with me on this beauty!

I put the stem back on the Comoy’s Facet 215 Smooth Bent Billiard and took it to the buffer. I buffed the bowl and stem with Blue Diamond to polish the briar and the vulcanite. Blue Diamond does a great job on the smaller scratches that remain in both. I gave the bowl and the stem several coats of carnauba wax and buffed the pipe with a clean buffing pad to raise the shine. I hand buffed it with a microfiber cloth to deepen the shine. I am amazed at how well it turned out. The finished pipe is shown in the photos below. This is beautiful smooth finished Comoy’s Facet 215 Bent Billiard with brass faceted bands and the vulcanite saddle stem combine to give the pipe a great look. The dimensions of the pipe are Length: 5 inches, Height: 1 ¾ inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 ¼ inches, Chamber diameter: ¾ of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 2.05 ounces/59 grams. This is another pipe that I will be putting on the rebornpipes online store in the British Pipe Makers Section shortly, if you are interested in adding it to your collection. Thanks for walking through the restoration with me on this beauty!

As always, I encourage your questions and comments as you read the blog. Thanks to each of you who are reading this blog. Remember we are not pipe owners; we are pipe men and women who hold our pipes in trust until they pass on into the trust of those who follow us.