by Steve Laug

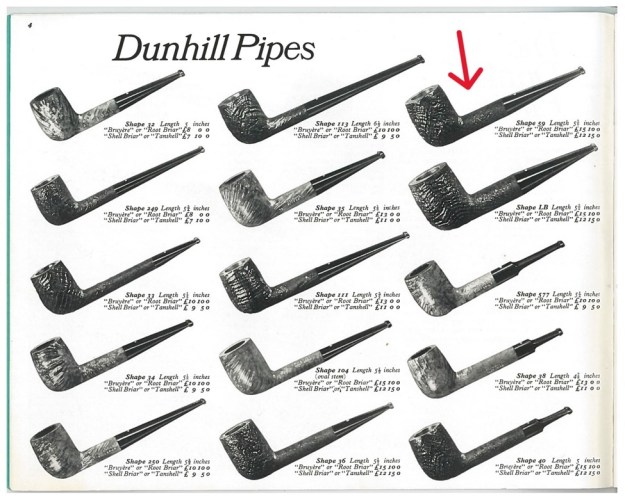

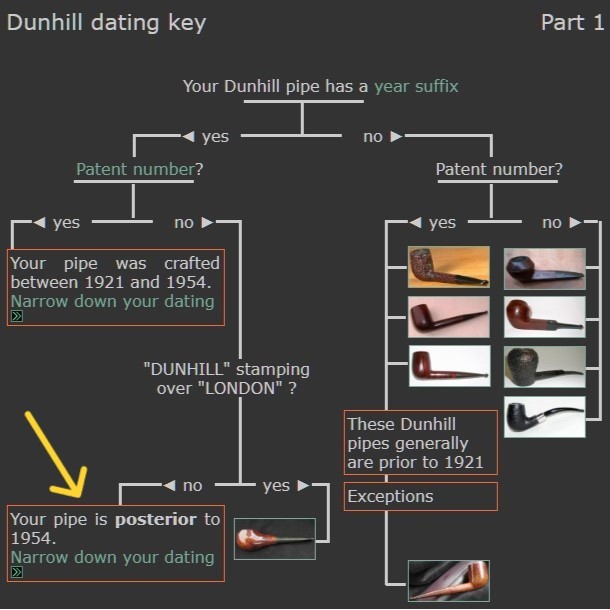

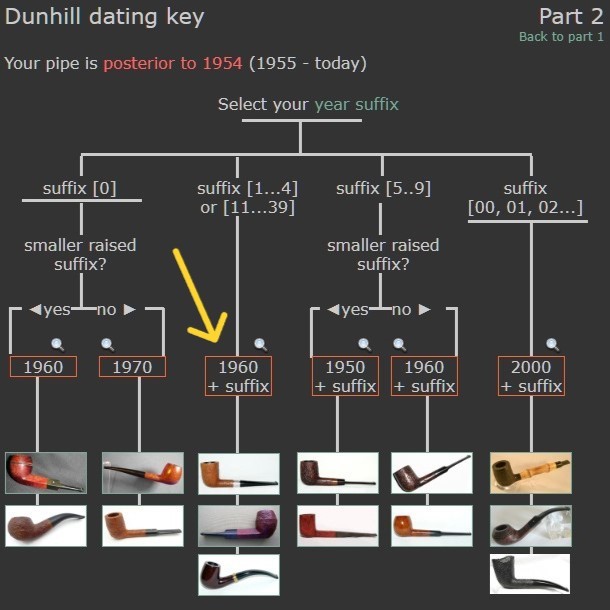

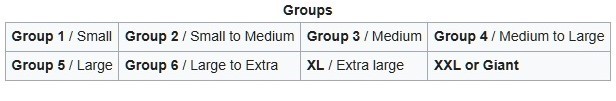

The next pipe on the work table is a pipe that we picked up from an eBay seller in Jordan, Minnesota, USA on 01/22/2024. This one was a nice looking sandblast Brandy that has a classic Barling look. It is stamped on the underside of the shank and reads Barling in script [over] Make [over] International [over] Made in Denmark. On the shank end at the joint of the stem it is stamped with the shape number 911. On the top of the saddle stem it is stamped with the Barling cross logo. It has some smooth panels mid bowl on the left and right side. The sandblast around the bowl shows some nice grain patterns. There was lot of grime and oils ground into the finish around the bowl and the shank. The pipe was dirty but the contrasting dark and medium brown stains highlighted the grain of the briar. There was a thick cake in the bowl. The rim top had a thick coat of lava overflowing from the bowl. The edges looked good but a clean up would tell the story. The rim top was crowned. The stem is a vulcanite saddle shape that has the Barling cross on the top of the saddle. It was oxidized, calcified and had some tooth chatter and tooth marks on the top and underside ahead of the button. The pipe showed a lot of promise but it was a mess. Jeff took pictures of the pipe before he did his clean up work.

He took photos of the rim top and bowl as well as the stem surfaces to show the condition of the well smoked pipe. You can see the cake in the bowl and the lava on the inner edge and rim top. The outer edge of the bowl is in good condition. It appears to have a nicely rounded crown on the rim top. The stem was lightly oxidized, calcified and had scratches, tooth chatter and marks on both sides ahead of the button.

He took photos of the rim top and bowl as well as the stem surfaces to show the condition of the well smoked pipe. You can see the cake in the bowl and the lava on the inner edge and rim top. The outer edge of the bowl is in good condition. It appears to have a nicely rounded crown on the rim top. The stem was lightly oxidized, calcified and had scratches, tooth chatter and marks on both sides ahead of the button.

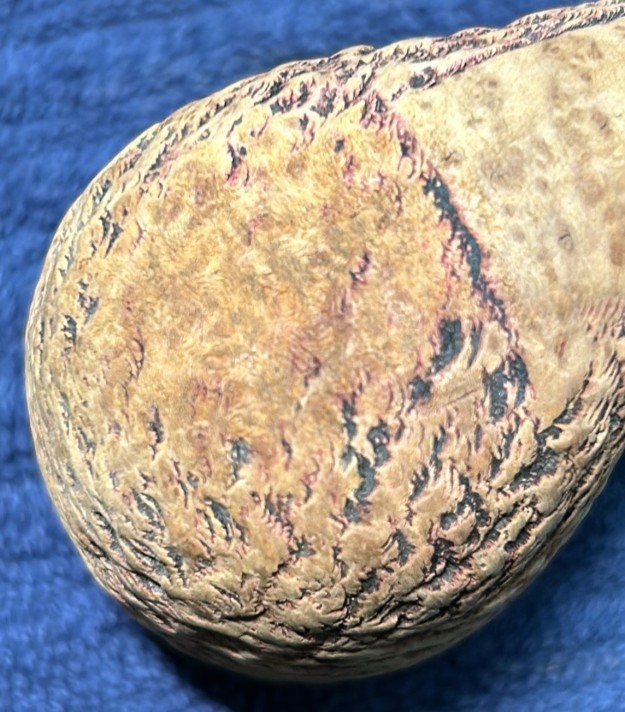

Jeff took some photos of the sides and heel of the bowl to give a sense of the sandblast finish and the grain around the bowl. It should clean up very well.

Jeff took some photos of the sides and heel of the bowl to give a sense of the sandblast finish and the grain around the bowl. It should clean up very well.

He captured the stamping on the sides of the shank and stem. It reads as noted above and is clear and readable. He also took photos of the Barling cross on the top of the saddle stem. The stem also has a white acrylic spacer that fits between the shank end and the stem face.

He captured the stamping on the sides of the shank and stem. It reads as noted above and is clear and readable. He also took photos of the Barling cross on the top of the saddle stem. The stem also has a white acrylic spacer that fits between the shank end and the stem face.

I like to do background research on the pipes I am working on. I did a quick search on the rebornpipes blog and found a blog written by Paresh that gives some great background information (https://rebornpipes.com/2019/09/16/a-fresh-lease-on-life-for-a-barling-t-v-f-911-made-in-denmark/). I quote from it below:

I like to do background research on the pipes I am working on. I did a quick search on the rebornpipes blog and found a blog written by Paresh that gives some great background information (https://rebornpipes.com/2019/09/16/a-fresh-lease-on-life-for-a-barling-t-v-f-911-made-in-denmark/). I quote from it below:

I had previously worked on a couple of Barling pipes from my inherited pipe collection; here are the links to both the write up, https://rebornpipes.com/2019/03/26/a-simple-restoration-of-an-early-transition-era-barling-2639/, https://rebornpipes.com/2018/12/10/decking-out-my-grandfathers-battered-pre-transition-barling-1354/ and had researched this brand then. To refresh my memory, I revisited the write ups and also pipedia.org. Here is an interesting excerpt from pipedia.org (https://pipedia.org/wiki/Barling)

In the late 1970’s production of Barling pipes was shifted to Denmark where Eric Nording manufactured Barling pipes for Imperial. There may have been other factories, but as of this writing, none has been identified. Nording stated that he made approximately 100.000 pipes for Imperial.

Despite these attempts to diversify the line, Barling lost its market. These pipes just weren’t equivalent to the family era pipes. Finally, Imperial decided to close down the Barling operations entirely by 1980.

Paresh discerned from the above information that the pipe currently on his work table is from the period between late 1970’s to 1980 and most likely carved by master craftsman Eric Nording!! For me the fascinating thing is that the pipe I am working on is from the same master and the same carver.

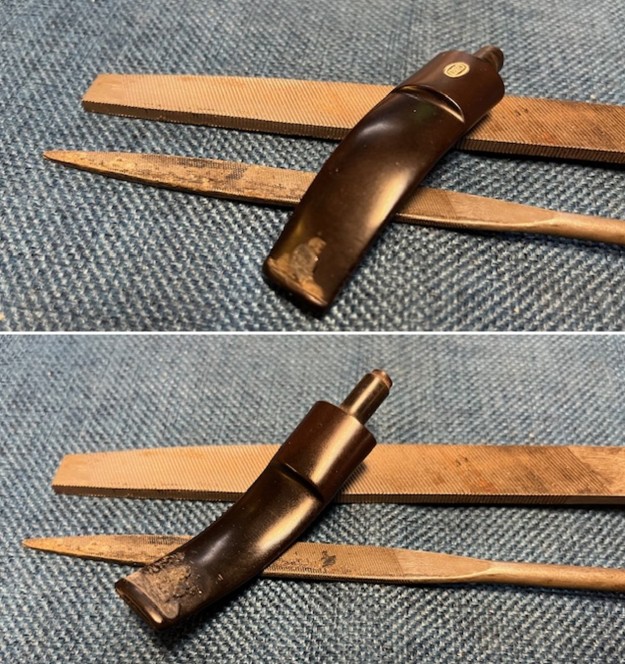

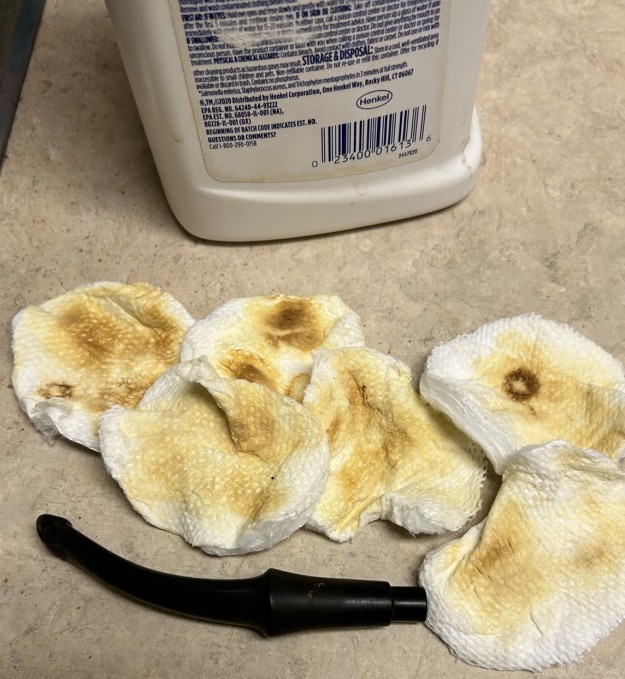

Now it was time to look at it up close and personal. Jeff had removed the cake and the lava on the rim top. He had reamed the bowl with a PipNet Pipe Reamer and cleaned up the remnants with a Savinelli Fitsall Pipe Knife. He took the cake back to bare briar so we could check the walls for damage. He scrubbed the exterior of the bowl with Murphy’s Oil Soap and a tooth brush to remove the grime on the bowl and rim and was able to remove the lava and dirt. He cleaned out the interior of the bowl and shank with shank brushes, pipe cleaners, cotton swabs and alcohol until they came out clean. He cleaned the stem with Soft Scrub to remove the grime on the exterior. He cleaned out the airway with alcohol, cotton swabs and pipe cleaners. I took some photos of the pipe before I started my work on it today.

I took a close up photo of the cleaned up rim top. The rim top and the inner edge look good. The bowl is clean and the walls are undamaged. The stem looks good with some tooth chatter and marks along the top and underside ahead of the button. The Barling Cross is faded with the cleaning.

I took a close up photo of the cleaned up rim top. The rim top and the inner edge look good. The bowl is clean and the walls are undamaged. The stem looks good with some tooth chatter and marks along the top and underside ahead of the button. The Barling Cross is faded with the cleaning. I took a photo of the stamping on the shank side. It is clear and readable as noted above. I took the stem off the pipe and took a photo. The thick shank billiard is an attractive looking pipe with nice lines. The taper stem shows tooth damage on the top and undersides of the stem.

I took a photo of the stamping on the shank side. It is clear and readable as noted above. I took the stem off the pipe and took a photo. The thick shank billiard is an attractive looking pipe with nice lines. The taper stem shows tooth damage on the top and undersides of the stem.

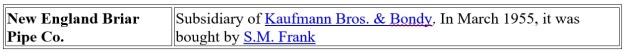

I started my work on the pipe by working over the rim top and the bowl and shank with a 320 grit sanding pad. I wiped the bowl down after sanding pad. The rim top began to take on a shine.

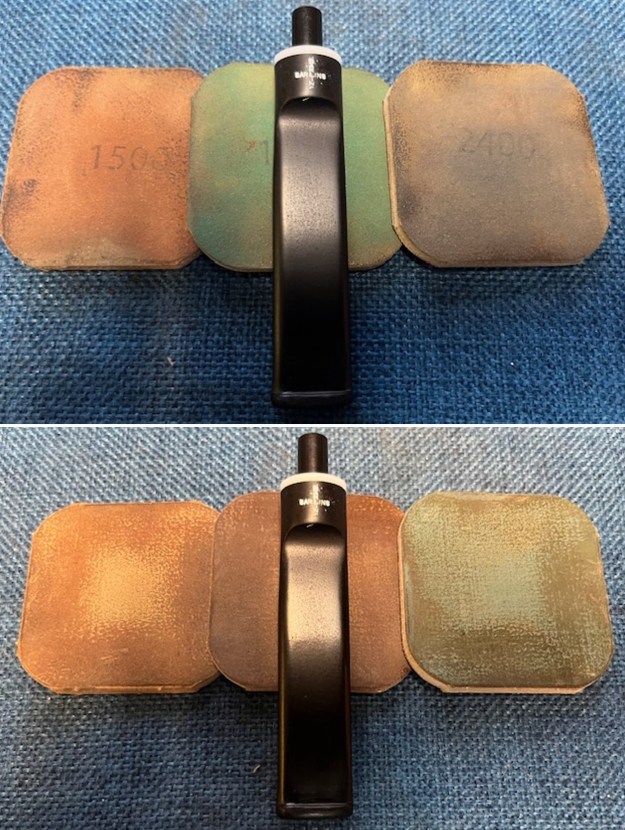

I started my work on the pipe by working over the rim top and the bowl and shank with a 320 grit sanding pad. I wiped the bowl down after sanding pad. The rim top began to take on a shine. I polished the rim top with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding with 1500-12000 grit pads. I wiped the rim top down after each sanding pad with a damp cloth. It really took on a shine.

I polished the rim top with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding with 1500-12000 grit pads. I wiped the rim top down after each sanding pad with a damp cloth. It really took on a shine.

I rubbed the bowl down with Before & After Restoration Balm. I worked it into the surface of the briar with my fingertips where it works to clean, restore and preserve the briar. I let it do its magic for 15 minutes then buffed it off with a cotton cloth. The pipe looks incredibly good at this point in the process.

I rubbed the bowl down with Before & After Restoration Balm. I worked it into the surface of the briar with my fingertips where it works to clean, restore and preserve the briar. I let it do its magic for 15 minutes then buffed it off with a cotton cloth. The pipe looks incredibly good at this point in the process.

I set aside the bowl and turned my attention to the stem. I touched up the stamping on the topside of the saddle stem with white acrylic fingernail polish. I pointed it on with the applicator and scraped off the excess and lightly sanded it with a 1500 grit micromesh pad.

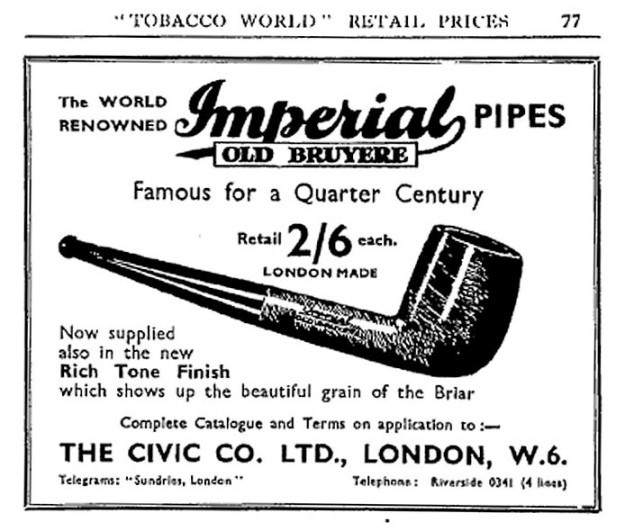

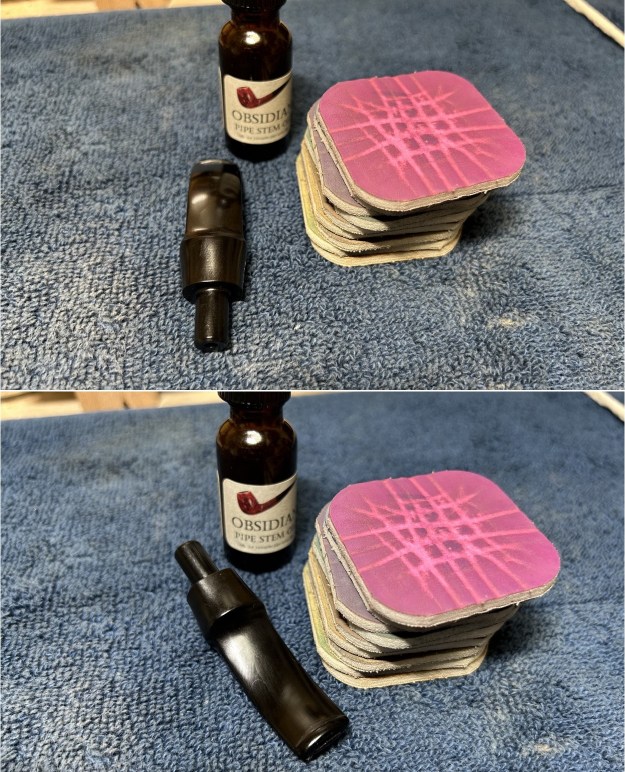

I set aside the bowl and turned my attention to the stem. I touched up the stamping on the topside of the saddle stem with white acrylic fingernail polish. I pointed it on with the applicator and scraped off the excess and lightly sanded it with a 1500 grit micromesh pad. I “painted” the surface of the stem with the flame of a lighter. I was able to raise all of the tooth marks. I sanded out the light remnants that remained with a folded piece of 220 grit sandpaper. Once finished I wiped it down with an Obsidian Oil impregnated cloth. It looked much better.

I “painted” the surface of the stem with the flame of a lighter. I was able to raise all of the tooth marks. I sanded out the light remnants that remained with a folded piece of 220 grit sandpaper. Once finished I wiped it down with an Obsidian Oil impregnated cloth. It looked much better.

I continued to polish the stem with micromesh sanding pads – wet sanding with 1500-12000 grit sanding pads. I wiped it down after each sanding pad with Obsidian Oil. I polished it further with Before & After Stem Polish – both Fine and Extra Fine. I gave it a final coat of Obsidian Oil and set it aside to absorb the oil.

I continued to polish the stem with micromesh sanding pads – wet sanding with 1500-12000 grit sanding pads. I wiped it down after each sanding pad with Obsidian Oil. I polished it further with Before & After Stem Polish – both Fine and Extra Fine. I gave it a final coat of Obsidian Oil and set it aside to absorb the oil.

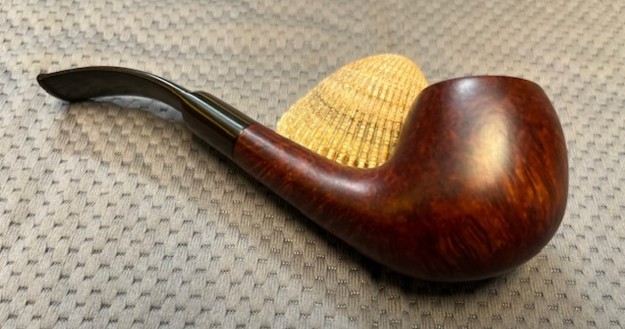

I am excited to finish this Made in Denmark Barling Make International 911 Brandy made by Eric Nording. I put the pipe back together and buffed it with Blue Diamond on the buffing wheel. I gave the bowl multiple coats of Conservator’s Wax and the stem multiple coats of carnauba wax. I buffed the pipe with a clean buffing pad to raise the shine and then by hand with a microfibre cloth to deepen it. It is fun to see what the polished bowl looks like with beautiful sandblast grain all around the bowl and shank and the smooth well grained crowned rim top. The polished grain on the pipe looks great with the black hard rubber stem. This Danish Barling Make International 911 Brandy is great looking and the pipe feels great in my hand. It is light and well balanced. Have a look at it with the photos below. The dimensions are Length: 6 inches, Height: 2 inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 inch, Chamber diameter: ¾ of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 44 grams/1.55 ounces. It turned out to be a beautiful pipe. I will soon be putting it on the rebornpipes store in the Danish Pipemakers Section. If you are interested in adding it to your collection let me know. Remember we are the next in a long line of pipe men and women who will carry on the trust of our pipes until we pass them on to the next trustee. Thanks for your time reading this blog.

I am excited to finish this Made in Denmark Barling Make International 911 Brandy made by Eric Nording. I put the pipe back together and buffed it with Blue Diamond on the buffing wheel. I gave the bowl multiple coats of Conservator’s Wax and the stem multiple coats of carnauba wax. I buffed the pipe with a clean buffing pad to raise the shine and then by hand with a microfibre cloth to deepen it. It is fun to see what the polished bowl looks like with beautiful sandblast grain all around the bowl and shank and the smooth well grained crowned rim top. The polished grain on the pipe looks great with the black hard rubber stem. This Danish Barling Make International 911 Brandy is great looking and the pipe feels great in my hand. It is light and well balanced. Have a look at it with the photos below. The dimensions are Length: 6 inches, Height: 2 inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 inch, Chamber diameter: ¾ of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 44 grams/1.55 ounces. It turned out to be a beautiful pipe. I will soon be putting it on the rebornpipes store in the Danish Pipemakers Section. If you are interested in adding it to your collection let me know. Remember we are the next in a long line of pipe men and women who will carry on the trust of our pipes until we pass them on to the next trustee. Thanks for your time reading this blog.