by Kenneth Lieblich

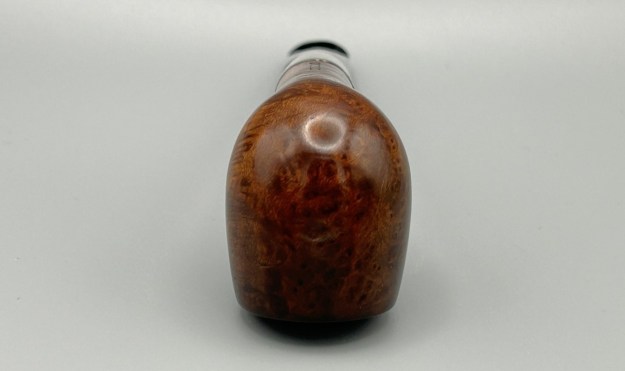

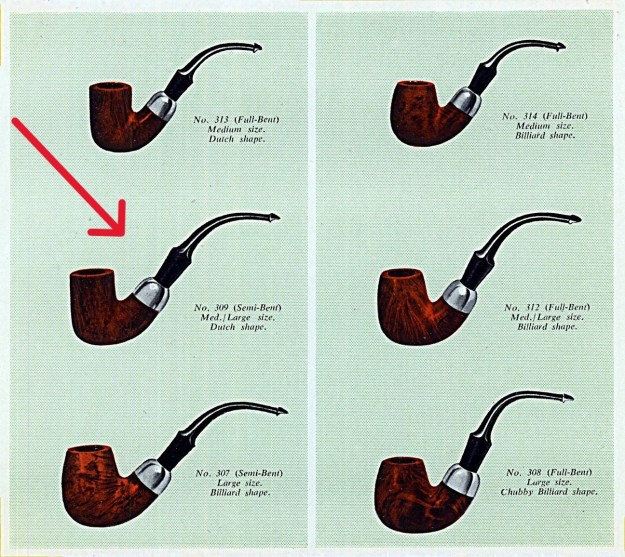

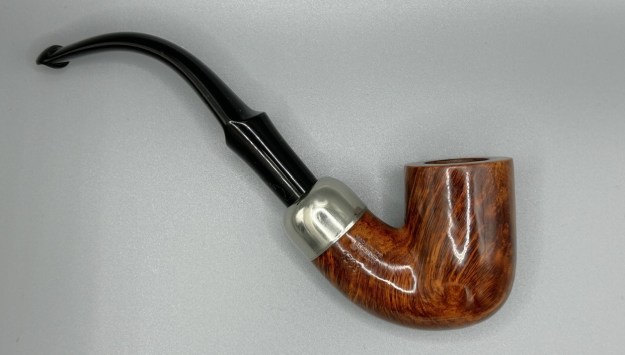

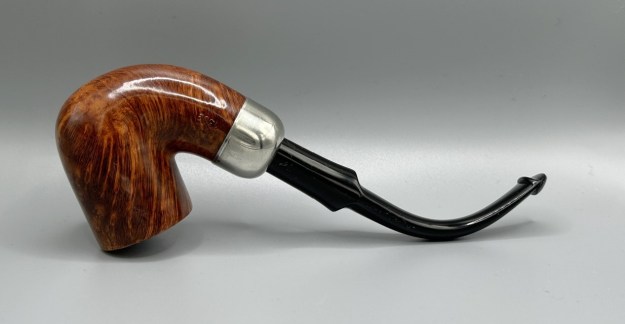

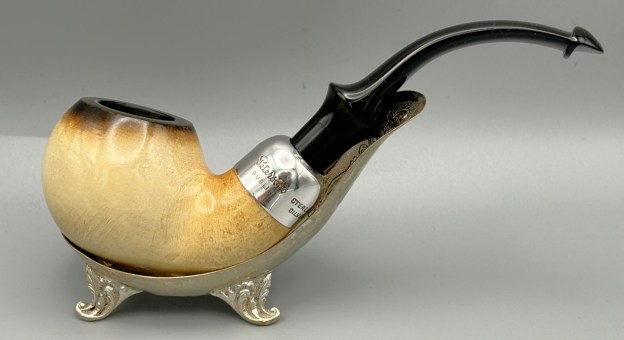

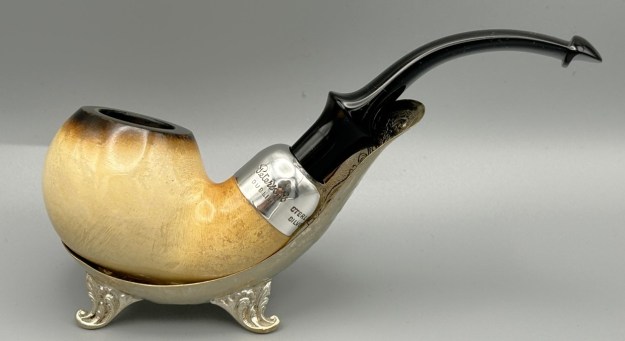

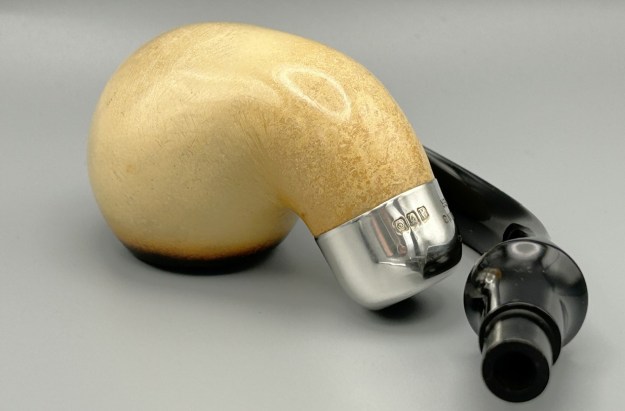

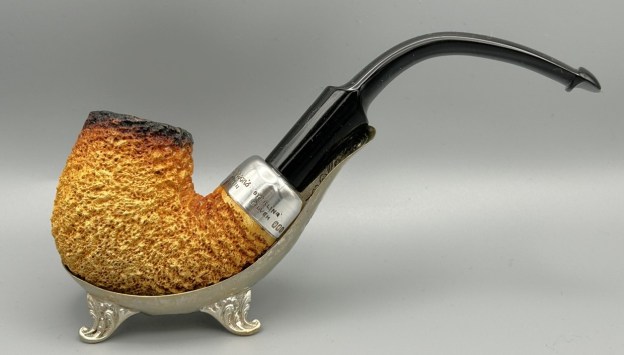

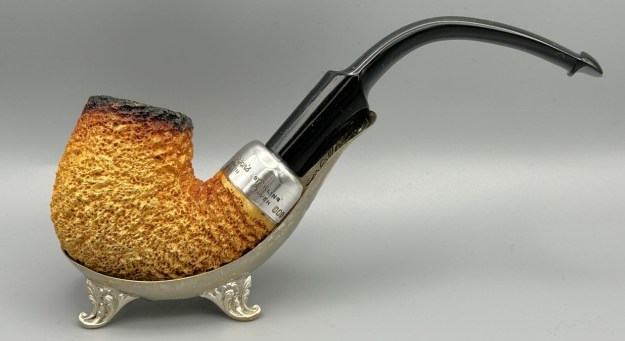

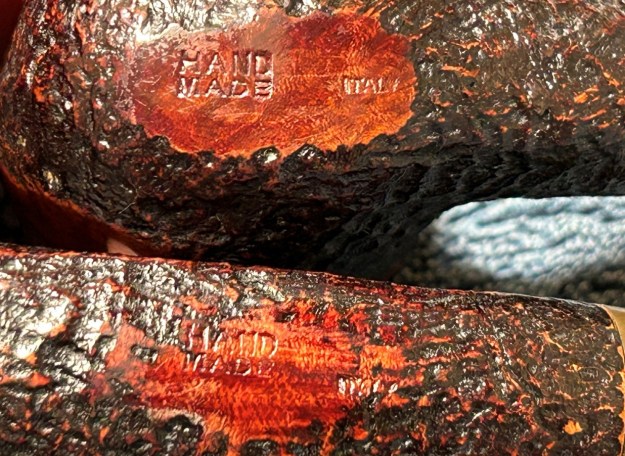

I recently came upon this calabash pipe and it’s a bit of a stunner. It is so bountiful and robust – it’s one of the most attractive calabashes I’ve ever worked on. There is an elegance to this pipe, and its curves remind me of an alpine piste de ski. Really nice looking, and in good shape. Maybe this is the pipe for you! No markings at all on this pipe, but no matter.

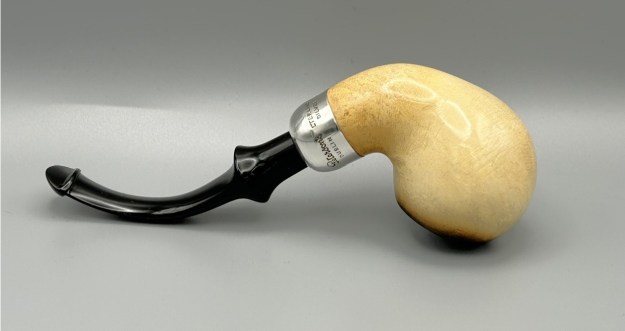

Let’s take a closer look at it. The bowl is beautifully-shaped meerschaum. It has some minor signs of wear, but nothing serious. Similarly, the gourd is in lovely condition. No wear to speak of and the cork gasket is perfect. The gourd also has an acrylic shank extension in nice shape. Finally, the vulcanite stem is also great. It has some oxidation and some small signs of wear, but nothing to worry about.

Let’s take a closer look at it. The bowl is beautifully-shaped meerschaum. It has some minor signs of wear, but nothing serious. Similarly, the gourd is in lovely condition. No wear to speak of and the cork gasket is perfect. The gourd also has an acrylic shank extension in nice shape. Finally, the vulcanite stem is also great. It has some oxidation and some small signs of wear, but nothing to worry about.

I used isopropyl alcohol on a few cotton rounds and wiped down the stem to provide an initial cleaning of filth before moving on to the next steps. The primary cleaning came next. I disinfected the inside of the stem with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. I scrubbed thoroughly to make sure the interior was very clean.

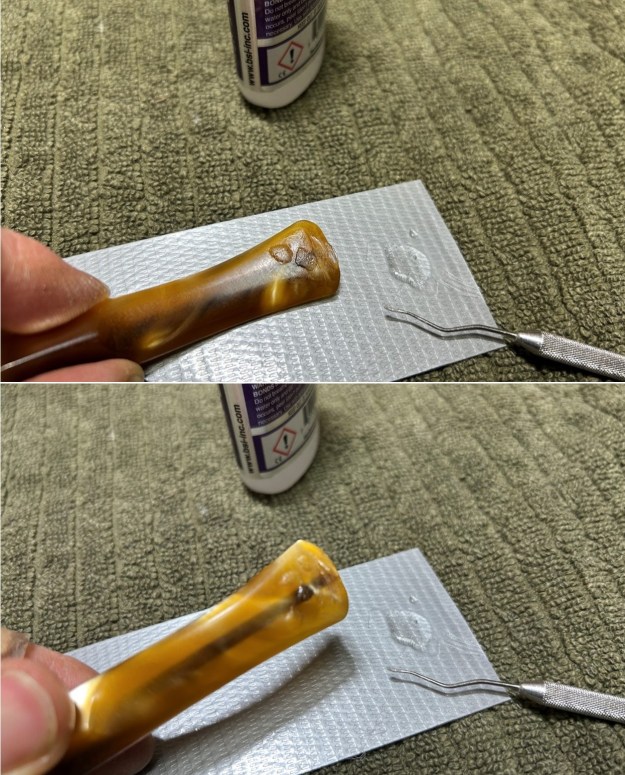

I used isopropyl alcohol on a few cotton rounds and wiped down the stem to provide an initial cleaning of filth before moving on to the next steps. The primary cleaning came next. I disinfected the inside of the stem with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. I scrubbed thoroughly to make sure the interior was very clean.  The goal of the next step is the removal (or minimization) of oxidation. Going to my sink, I used cream cleanser, cotton rounds, and a toothbrush, and scoured the stem to remove as much surface oxidation as possible. As the photos show, the result was a hideous, ochre-coloured mess – but better off the stem than on it.

The goal of the next step is the removal (or minimization) of oxidation. Going to my sink, I used cream cleanser, cotton rounds, and a toothbrush, and scoured the stem to remove as much surface oxidation as possible. As the photos show, the result was a hideous, ochre-coloured mess – but better off the stem than on it. Once the stem was reasonably clean, I soaked it overnight in some Briarville Stem Oxidation Remover. This solution works to draw oxidation in the stem to the surface of the vulcanite. This is a major aid and an important step in ensuring a clean stem. The following day, I drew out the stem from its bath and scrubbed the lingering fluid with a toothbrush.

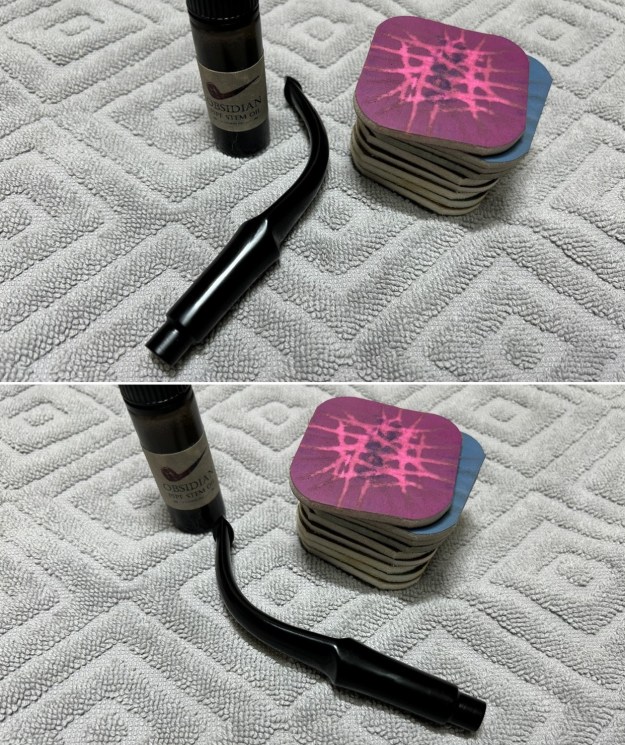

Once the stem was reasonably clean, I soaked it overnight in some Briarville Stem Oxidation Remover. This solution works to draw oxidation in the stem to the surface of the vulcanite. This is a major aid and an important step in ensuring a clean stem. The following day, I drew out the stem from its bath and scrubbed the lingering fluid with a toothbrush. The penultimate step for the stem is sanding. I used all nine of the micromesh sanding pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand out flaws, even out the vulcanite, and provide gentle polishing of the finished surface. I also applied pipe-stem oil while using the last five micromesh pads. There was a wonderful, deep black shine to the stem when I was done.

The penultimate step for the stem is sanding. I used all nine of the micromesh sanding pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand out flaws, even out the vulcanite, and provide gentle polishing of the finished surface. I also applied pipe-stem oil while using the last five micromesh pads. There was a wonderful, deep black shine to the stem when I was done. As the stem was (nearly) complete, I moved on to the bowl. The first step was to ream it out – that is to say, remove all the cake inside the bowl. This accomplished a couple of things. First (and most obviously), it cleaned the bowl and provided a refurbished chamber for future smoking. Second, when the old cake was removed, I could inspect the interior walls of the bowl and determine if there was damage or not. Meerschaum is too fragile for a proper reamer, so I used 220-grit sandpaper on the end of a wooden dowel to clean out the bowl and it turned out very well. One of the frustrations of cleaning meerschaum is that once smoked, the stains never go away. However, I did what I could and it definitely improved.

As the stem was (nearly) complete, I moved on to the bowl. The first step was to ream it out – that is to say, remove all the cake inside the bowl. This accomplished a couple of things. First (and most obviously), it cleaned the bowl and provided a refurbished chamber for future smoking. Second, when the old cake was removed, I could inspect the interior walls of the bowl and determine if there was damage or not. Meerschaum is too fragile for a proper reamer, so I used 220-grit sandpaper on the end of a wooden dowel to clean out the bowl and it turned out very well. One of the frustrations of cleaning meerschaum is that once smoked, the stains never go away. However, I did what I could and it definitely improved. I sanded down the entire piece of meerschaum with my micromesh pads. I also rubbed some Clapham’s Beeswax into the meerschaum. Then I let it sit for 20 minutes, buffed it with a microfiber cloth and then repeated the beeswax process. Worked like a charm!

I sanded down the entire piece of meerschaum with my micromesh pads. I also rubbed some Clapham’s Beeswax into the meerschaum. Then I let it sit for 20 minutes, buffed it with a microfiber cloth and then repeated the beeswax process. Worked like a charm!

I wiped down the outside of the gourd, using a solution of a pH-neutral detergent and some distilled water, with cotton rounds. I cleaned inside the gourd gently by scraping with my reaming knife and some tube brushes. I was pleased with the results.

I wiped down the outside of the gourd, using a solution of a pH-neutral detergent and some distilled water, with cotton rounds. I cleaned inside the gourd gently by scraping with my reaming knife and some tube brushes. I was pleased with the results.

I sanded down the acrylic shank extension (but not the gourd) with only the finest of the micromesh pads. I also cleaned out the inside with cotton swabs and alcohol. It wasn’t very dirty. I then coated the gourd with LBE Before & After Restoration Balm and let it sit for 30 minutes. After that, I buffed it with the microfibre cloth.

I sanded down the acrylic shank extension (but not the gourd) with only the finest of the micromesh pads. I also cleaned out the inside with cotton swabs and alcohol. It wasn’t very dirty. I then coated the gourd with LBE Before & After Restoration Balm and let it sit for 30 minutes. After that, I buffed it with the microfibre cloth.

Finally, I applied some light lubricant to the cork gasket. Even though the gasket was in perfect shape, it’s a good idea to lubricate it in this way in order to maintain its elasticity. I set it aside to absorb and moved on.

Finally, I applied some light lubricant to the cork gasket. Even though the gasket was in perfect shape, it’s a good idea to lubricate it in this way in order to maintain its elasticity. I set it aside to absorb and moved on. Before I went off to the buffer, I gave the meer and the gourd another going over with Clapham’s beeswax rub. This really worked well. I only took the stem to the buffer, as meerschaum and gourds don’t tolerate those high speeds very well!

Before I went off to the buffer, I gave the meer and the gourd another going over with Clapham’s beeswax rub. This really worked well. I only took the stem to the buffer, as meerschaum and gourds don’t tolerate those high speeds very well!

This big gourd calabash was a delight from the start and its beauty only increased through the restoration process. I am pleased to announce that this pipe is for sale! If you are interested in acquiring it for your collection, please have a look in the ‘Calabash’ section of the store here on Steve’s website. You can also email me directly at kenneth@knightsofthepipe.com. The approximate dimensions of the pipe are as follows: length 7 in. (178 mm); height 5⅞ in. (149 mm); bowl diameter 2⅞ in. (75 mm); chamber diameter 1 in. (26 mm). The weight of the pipe is 4⅝ oz. (132 g). I hope you enjoyed reading the story of this pipe’s restoration as much as I enjoyed restoring it. If you are interested in more of my work, please follow me here on Steve’s website or send me an email. Thank you very much for reading and, as always, I welcome and encourage your comments.