Blog by Steve Laug

The next pipe on the table is a beautiful Castello Sea Rock Briar Poker. I love the Sea Rock Briar finish and this was one that is quite exemplary of the finish. It has a less rugged and more refined rustication that is still tactile and I think will be a great smoker. It is a pipe that we purchased in September 2020 from a fellow in Los Angeles, California, USA.

This Castello Sea Rock Poker is stamped on the heel and the underside of the shank and reads 87P on the heel of the bowl. That is followed on the shank by Castello [over] Sea Rock Briar followed by Made in Cantu [over] Italy. The numbers and stamping tell me that the pipe is a Sea Rock rusticated finish and it is a Poker. The underside of the Lucite stem also had stamping that read Hand Made over Castello [over] the number 3. The finish was incredibly dirty with spots of grime and debris ground into the crevices and valleys of the rustication. The bowl had a thick cake in the and a heavy lava overflowing onto the smooth rim top. The rim top appeared to rough and beat up with dents. The inner and outer edge of the rim looked very good. The acrylic stem had tooth marks and chatter on both sides ahead of the button and on the button itself. Jeff took photos of the pipe before he started his clean up work on it.

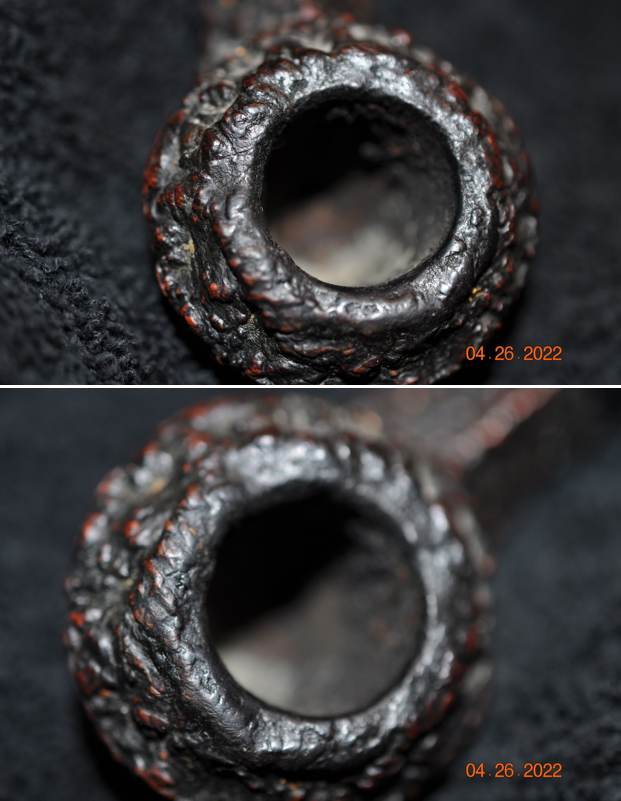

My brother took some close up photos of the rim top and the cake in the bowl to show what it looked like when we received it. You can see how thick the cake is and how much of the rim rustication has filled in with the overflow. The photos of the stem show the faux diamond logo on the top left side of the saddle. You can see the tooth marks and chatter near the button on both sides of the stem.

My brother took some close up photos of the rim top and the cake in the bowl to show what it looked like when we received it. You can see how thick the cake is and how much of the rim rustication has filled in with the overflow. The photos of the stem show the faux diamond logo on the top left side of the saddle. You can see the tooth marks and chatter near the button on both sides of the stem.

Jeff took photos of the rusticated finish around the bowl sides and heel. It is nice looking if you can see through the grime and dust ground into the rugged, deep rustication.

Jeff took photos of the rusticated finish around the bowl sides and heel. It is nice looking if you can see through the grime and dust ground into the rugged, deep rustication.

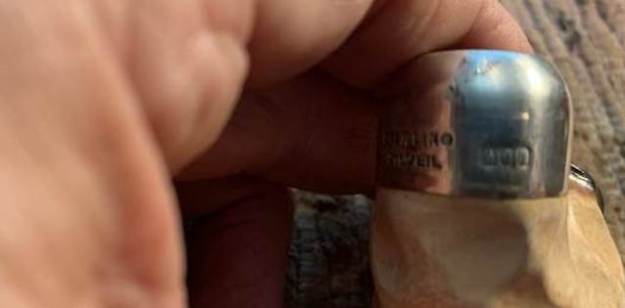

He took a photo of the stamping on the left underside of the diamond shank. The stamping is readable but filthy. It reads as noted above.

He took a photo of the stamping on the left underside of the diamond shank. The stamping is readable but filthy. It reads as noted above.  I recently wrote a blog on the Castello Sea Rock Briar Bulldog SC 54P. I reread the information and quote from a 54P Blog I wrote earlier (https://rebornpipes.com/2016/12/18/an-estate-sale-find-a-castello-sea-rock-sc-54p-bulldog/). It gives a short summary of the information I found.

I recently wrote a blog on the Castello Sea Rock Briar Bulldog SC 54P. I reread the information and quote from a 54P Blog I wrote earlier (https://rebornpipes.com/2016/12/18/an-estate-sale-find-a-castello-sea-rock-sc-54p-bulldog/). It gives a short summary of the information I found.

Before I worked on the pipe I wanted to do a bit of research to see if I could shed some more light on the pipe I had in hand. I learned from the pipephil website that the rhinestone logo was originally on pipes for the US market. There was no hint as to why that was done only that it was and that it is occasionally still used http://www.pipephil.eu/logos/en/logo-castello.html

I have an older article called PCCA’s Castello Grade & Style Guide. It was written by Robert C. Hamlin (c) 1988, 1992, 1994. Robert gathered some remarkable information on the Castello lines and I have often used his guide in the past to give me pertinent data. There I found more information regarding the shiny logo on the side of the stem.

“American logo’d Castello pipes use a small round “Diamond” (referred to and looking like, but it is NOT actually a diamond) inlaid into the mouthpiece. This was originally done so that the standard Castello white bar logo did not conflict with another brand and logo that was sold by Wally Frank called the “White Bar Pipe” (in the 1950’s).”

The above quote and the remainder of those following come from the same article by Robert Hamlin. You can read the full article at the following link: http://www.pipes.org/BURST/FORMATTED/196.016.html

I read further in the article to help me understand the stamping on the underside of the shank. My knowledge of Castello pipes is pretty limited so when I get one to restore I resort to this article and others to try to make heads or tails of the stamping.

I learned that the Sea Rock Briar stamp also signified something and told me more about the pipe. Robert pointed out:

“SEA ROCK [Carved Black or dark brown]: This is the lowest grade of the Castello line and is the most common in the USA. Sea Rocks are produced by taking a smooth bowl that has not been “final finished” and surface carving the finish with tools. This “carved” finish is then evened out using a steel wire brush, stained and then waxed. The Natural Vergin carved finish is left unstained and unwaxed as a rule, although we have seen waxed and partially waxed “Vergins”.”

The remaining mystery for me was the meaning of the stamping on the stem. I of course understood the Hand Made and the Castello stamping but the number 3 was a mystery to me. I was not sure what it referred to. So once again Robert’s article gave me the information I needed to understand that last piece of the mystery.

“#2: All Castello standard shaped pipes have a number (3, 4, 5 or 6) stamped on the mouthpiece or sometimes on the Lucite ferrule. What does this number mean? Not much really, it is the number of the size for the proper straw tube or reed that fits the shank and stem of the pipe. These straw tubes are rarely used in the United States. The Castello reed is considered superfluous and useless to most, but with this number you will always know which one fits (the different numbers have to do with length, not diameter).”

Armed with that information I turned to work on the pipe itself. Before he sent it to me, Jeff had done an amazing job cleaning the pipe. It almost looked like a different pipe after his work. He reamed the pipe with a PipNet pipe reamer and removed the rest of it with a Savinelli Fitsall Pipe Knife. He scrubbed the bowl with undiluted Murphy’s Oil Soap with a tooth brush. He rinsed it under running warm water to remove the soap and grime. He cleaned out the inside of the shank and the airway in the stem with isopropyl alcohol, cotton swabs and pipe cleaners. Even though the stem was acrylic he soaked the stem in Briarville’s Pipe Stem Deoxidizer and then rinsed it off with warm water. It really works well to remove internal and external grime and tars. He scrubbed the stem with Soft Scrub and a tooth brush and rinsed it off with warm water. It looked amazing when I took it out of the package of pipes he shipped me. I took photos of the pipe before I started my part of the restoration work.

The rim top was much cleaner and the edges looked good. However, the surface of the rim had been used as a hammer and it was in rough condition. Fortunately none of them were too deep – probably thanks to the think overflow of lava. It would take some work to clean up but it had great potential. The stem surface looked good but visible tooth marks and chatter showed clearly on either side of the stem.

The rim top was much cleaner and the edges looked good. However, the surface of the rim had been used as a hammer and it was in rough condition. Fortunately none of them were too deep – probably thanks to the think overflow of lava. It would take some work to clean up but it had great potential. The stem surface looked good but visible tooth marks and chatter showed clearly on either side of the stem.  I took photos of the stamping on the underside of the bowl, shank and stem. It is clear and readable as noted above.

I took photos of the stamping on the underside of the bowl, shank and stem. It is clear and readable as noted above. I took the stem off the shank and took photos of the parts of the pipe. It is a great looking rusticated Poker.

I took the stem off the shank and took photos of the parts of the pipe. It is a great looking rusticated Poker.  I worked on the rim top and the heel of the bowl to minimize the scratches and marks on both. I used micromesh sanding pads and wet sanded with 1500-12000 grit pads. I was fortunate that the scratches were not deep so I was able to polish them out and remove them. The rim top looked amazingly better and it is a pretty looking pipe.

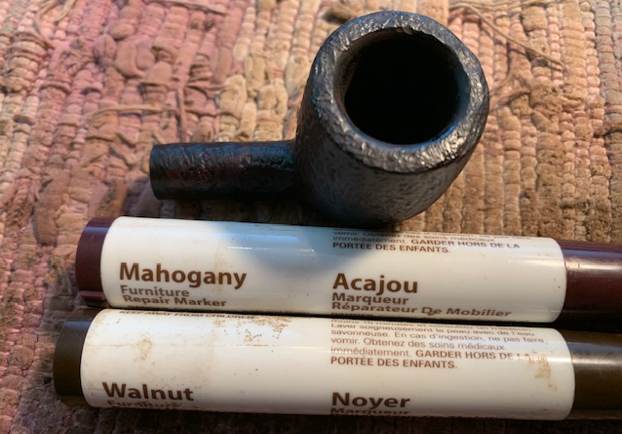

I worked on the rim top and the heel of the bowl to minimize the scratches and marks on both. I used micromesh sanding pads and wet sanded with 1500-12000 grit pads. I was fortunate that the scratches were not deep so I was able to polish them out and remove them. The rim top looked amazingly better and it is a pretty looking pipe.

The bowl looked good at this point so I rubbed it down with Before & After Restoration Balm. I worked it into the surface of the bowl and shank with my fingertips and a horse hair shoe brush to clean, enliven and protect the briar. I let the balm sit for about 10-15 minutes and buffed with a cotton cloth to raise the shine.

The bowl looked good at this point so I rubbed it down with Before & After Restoration Balm. I worked it into the surface of the bowl and shank with my fingertips and a horse hair shoe brush to clean, enliven and protect the briar. I let the balm sit for about 10-15 minutes and buffed with a cotton cloth to raise the shine.

I set the bowl aside and turned my attention to the stem. I sanded the tooth marks out on both sides of the stem at the button using 220 grit sandpaper and also sanded the damage to the button surface itself. I started polishing the stem with 400 grit wet dry sandpaper.

I set the bowl aside and turned my attention to the stem. I sanded the tooth marks out on both sides of the stem at the button using 220 grit sandpaper and also sanded the damage to the button surface itself. I started polishing the stem with 400 grit wet dry sandpaper.  I used micromesh sanding pads to polish the newly sanded areas on the Lucite stem surface. I dry sanded it with 1500-12000 grit pads and wiped it down with the damp pad after each sanding pad. In doing so I was able to remove all signs of the damage to stem in those spots along the edge and top of the button.

I used micromesh sanding pads to polish the newly sanded areas on the Lucite stem surface. I dry sanded it with 1500-12000 grit pads and wiped it down with the damp pad after each sanding pad. In doing so I was able to remove all signs of the damage to stem in those spots along the edge and top of the button.

I put the stem in place in the shank and looked this beautiful Castello Sea Rock Briar 87P Poker. I lightly buffed the bowl on the buffing wheel. I buffed the stem with Blue Diamond polish on the buffing wheel I waxed the stem with carnauba wax on the wheel. I waxed the bowl with Conservator’s Wax and buffed the entire pipe with a clean buffing pad to raise the shine. I hand buffed it with a microfibre cloth to deepen the shine. The finished Castello Sea Rock Briar Poker is shown in the photos below. It is truly a beautiful little Poker. The dimensions of the pipe are Length: 5 ¾ inches, Height: 2 inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 ½ inches, Chamber diameter: ¾ of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 45 grams/1.59 ounces. The shape and the rustication make it a pleasure to hold in the hand. It fits snug with my thumb curled around the back of the bowl and the rest of the fingers holding the bowl. The finish is extremely tactile and should be interesting in hand as the bowl heats up during smoking. I can testify to how well Castellos smoke. I will be adding it to the Italian Pipe Makers Section on the rebornpipes store soon. Thanks for walking with me through the restoration process.

I put the stem in place in the shank and looked this beautiful Castello Sea Rock Briar 87P Poker. I lightly buffed the bowl on the buffing wheel. I buffed the stem with Blue Diamond polish on the buffing wheel I waxed the stem with carnauba wax on the wheel. I waxed the bowl with Conservator’s Wax and buffed the entire pipe with a clean buffing pad to raise the shine. I hand buffed it with a microfibre cloth to deepen the shine. The finished Castello Sea Rock Briar Poker is shown in the photos below. It is truly a beautiful little Poker. The dimensions of the pipe are Length: 5 ¾ inches, Height: 2 inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 ½ inches, Chamber diameter: ¾ of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 45 grams/1.59 ounces. The shape and the rustication make it a pleasure to hold in the hand. It fits snug with my thumb curled around the back of the bowl and the rest of the fingers holding the bowl. The finish is extremely tactile and should be interesting in hand as the bowl heats up during smoking. I can testify to how well Castellos smoke. I will be adding it to the Italian Pipe Makers Section on the rebornpipes store soon. Thanks for walking with me through the restoration process.