by Kenneth Lieblich

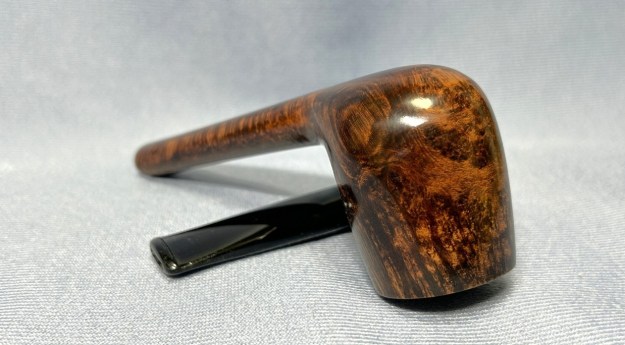

Here’s a real beauty. Recently, I was given the opportunity to purchase a small group of pipes by master pipemaker, Mark Tinsky. How could I say no? The answer, of course, is that I could not and I happily acquired them. This pipe is actually not one from the aforementioned lot, but was a Tinsky I already had. It seemed sensible to add it on to this series of pipe restorations. Whereas the others I restored recently were from the Canadian family of pipe shapes, this one, as you can see is a lovat. Or, perhaps, a lovat with a Dublin-like bowl. Another nice detail about this pipe is that it comes with its original pipe sock!

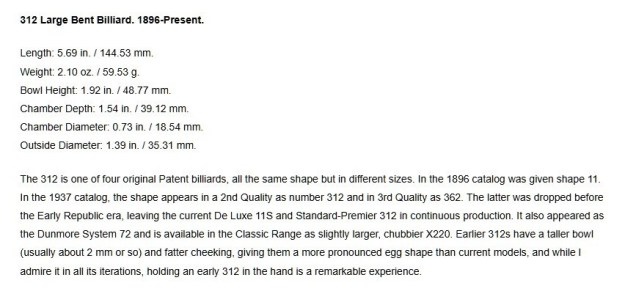

This is a beautiful pipe with fantastic, straight grain. The rim is just wonderful. It has a lovely, rich brown colour to it and a silky-smooth surface. This is an older Tinsky than the ones you’ve seen from me recently. The star logo on the side of the stem is different from previous ones, insofar as it is engraved into the acrylic. Under the shank are the markings and they read: American [over] Reg No [over] 081 GP MT 15. I’m not sure but I assume that the 081 tells us that the pipe was made in 1981; the GP indicates that Grecian plateau briar was used, MT indicates that Mark Tinsky made it himself; and I sadly have no idea what the 15 refers to.

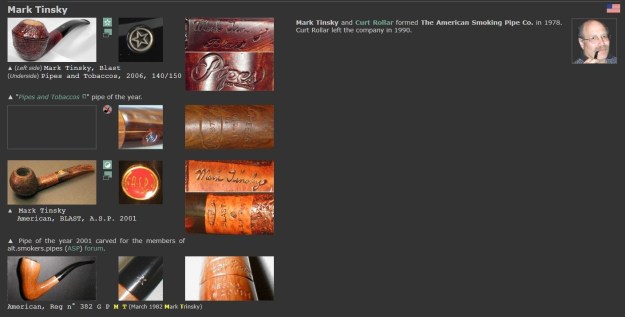

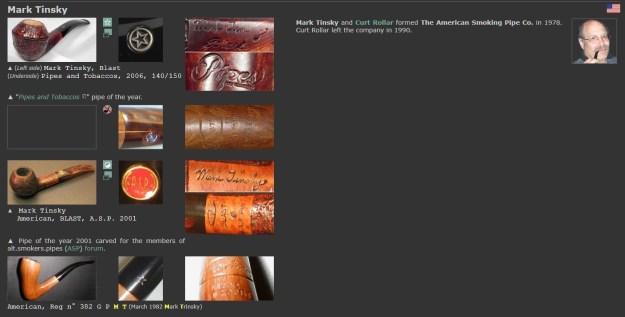

This is a beautiful pipe with fantastic, straight grain. The rim is just wonderful. It has a lovely, rich brown colour to it and a silky-smooth surface. This is an older Tinsky than the ones you’ve seen from me recently. The star logo on the side of the stem is different from previous ones, insofar as it is engraved into the acrylic. Under the shank are the markings and they read: American [over] Reg No [over] 081 GP MT 15. I’m not sure but I assume that the 081 tells us that the pipe was made in 1981; the GP indicates that Grecian plateau briar was used, MT indicates that Mark Tinsky made it himself; and I sadly have no idea what the 15 refers to. As I’m sure you know, Mark Tinsky is one of the great names in American pipe making. He is best summed up in this quotation from Erwin Van Hove:

As I’m sure you know, Mark Tinsky is one of the great names in American pipe making. He is best summed up in this quotation from Erwin Van Hove:

His more than reasonable prices, and his good-natured personality, have made Mark [Tinsky] the favorite of many Americans. It is difficult to find an amateur who does not possess at least one pipe made by the American Smoking Pipe Company, that Tinsky founded in 1978 with his friend Curt Rollar. In 1990, after the departure of his associate, Tinsky continued on by himself building a solid reputation using quality briar from Greece and stem blanks imported from Italy, offering collectors a vast assortment of models and finishes. In short, his pipes are beautiful and well-made pieces that produce a taste beyond reproach. Neither off-the-shelf nor haute couture, they are solid hand mades for an affordable price. There is a wonderful and extensive article on Tinsky, Rollar, and the American Smoking Pipe Company at Pipedia. I highly recommend reading it here. You can also visit his website: http://www.amsmoke.com/. There’s also a small blurb about him at Pipephil:

There is a wonderful and extensive article on Tinsky, Rollar, and the American Smoking Pipe Company at Pipedia. I highly recommend reading it here. You can also visit his website: http://www.amsmoke.com/. There’s also a small blurb about him at Pipephil: This pipe was in generally very nice shape – there were a few light marks on the rim – but nothing serious at all. The stem was also in good shape – a few bite marks, but the acrylic was sound and is easy to repair. This was clearly a well-maintained pipe.

This pipe was in generally very nice shape – there were a few light marks on the rim – but nothing serious at all. The stem was also in good shape – a few bite marks, but the acrylic was sound and is easy to repair. This was clearly a well-maintained pipe.

I used oil soap on a few cotton rounds and wiped down the stem to provide an initial cleaning before moving on to the next steps. The primary cleaning came next. I disinfected the inside of the stem with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. I scrubbed thoroughly to make sure the interior was very clean – but not much work was required as it was already pretty clean.

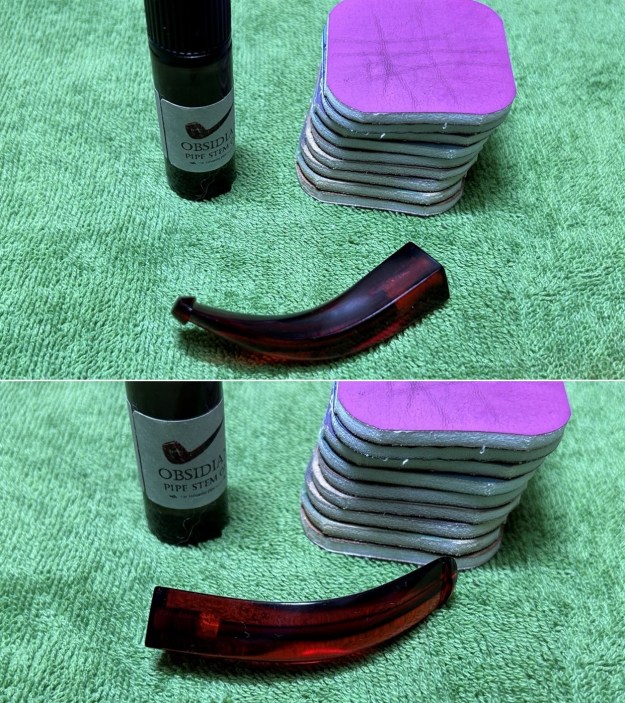

I used oil soap on a few cotton rounds and wiped down the stem to provide an initial cleaning before moving on to the next steps. The primary cleaning came next. I disinfected the inside of the stem with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. I scrubbed thoroughly to make sure the interior was very clean – but not much work was required as it was already pretty clean. I then set about fixing the marks in the acrylic. This was done by filling those divots with black cyanoacrylate adhesive, impregnated with carbon and rubber. I left this to cure. Following that, I used all nine of the micromesh sanding pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand out flaws, even out the acrylic, and provide gentle polishing of the finished surface. I also applied pipe-stem oil while using the last five micromesh pads. There was a wonderful, deep black shine to the stem when I was done.

I then set about fixing the marks in the acrylic. This was done by filling those divots with black cyanoacrylate adhesive, impregnated with carbon and rubber. I left this to cure. Following that, I used all nine of the micromesh sanding pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand out flaws, even out the acrylic, and provide gentle polishing of the finished surface. I also applied pipe-stem oil while using the last five micromesh pads. There was a wonderful, deep black shine to the stem when I was done. As the stem was (nearly) complete, I moved on to the stummel. The first step was to ream out the bowl – that is to say, remove all the cake inside the bowl. This accomplished a couple of things. First (and most obviously), it cleaned the bowl and provided a refurbished chamber for future smoking. Second, when the old cake was removed, I could inspect the interior walls of the bowl and determine if there was damage or not. I used a piece of sandpaper taped to a wooden dowel. This ensured that all the debris was removed. Again, like the stem, this didn’t take much work as the pipe was quite clean.

As the stem was (nearly) complete, I moved on to the stummel. The first step was to ream out the bowl – that is to say, remove all the cake inside the bowl. This accomplished a couple of things. First (and most obviously), it cleaned the bowl and provided a refurbished chamber for future smoking. Second, when the old cake was removed, I could inspect the interior walls of the bowl and determine if there was damage or not. I used a piece of sandpaper taped to a wooden dowel. This ensured that all the debris was removed. Again, like the stem, this didn’t take much work as the pipe was quite clean. I then cleaned the stummel with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol.

I then cleaned the stummel with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. To tidy up the briar, I also wiped down the outside with some oil soap on cotton rounds. This did a good job of cleaning any latent dirt on the surface of the briar. The last step of the cleaning process was to scour the inside of the stummel with some soap and tube brushes.

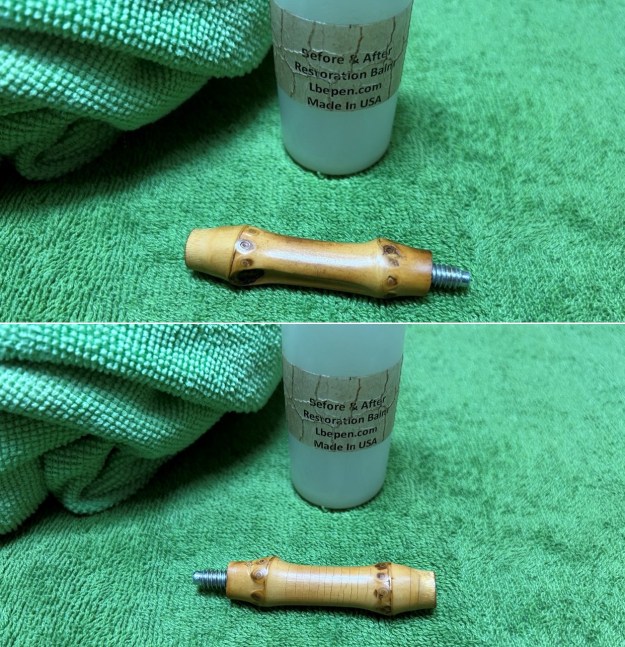

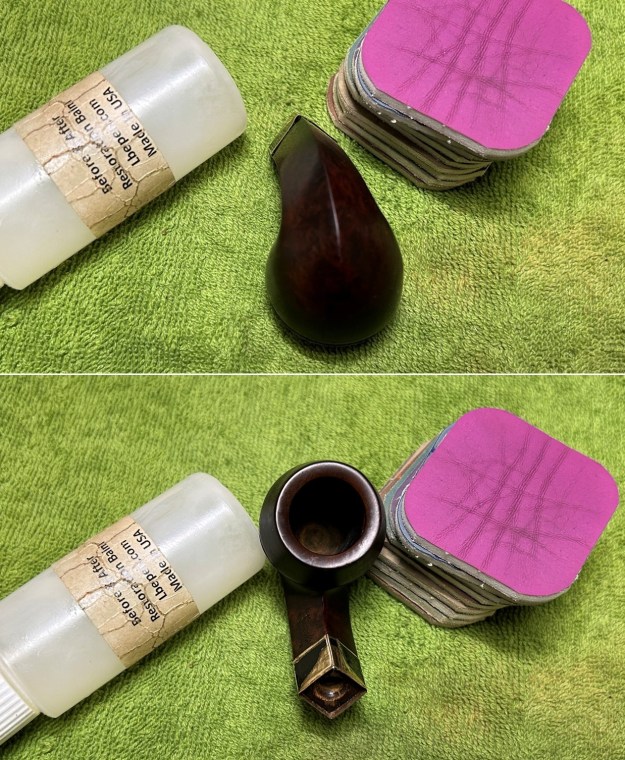

To tidy up the briar, I also wiped down the outside with some oil soap on cotton rounds. This did a good job of cleaning any latent dirt on the surface of the briar. The last step of the cleaning process was to scour the inside of the stummel with some soap and tube brushes. I used all nine micromesh pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand the whole stummel. This sanding minimizes flaws in the briar and provides a beautiful smoothness to the wood. I rubbed some LBE Before & After Restoration Balm into the briar and let it sit for 30 minutes or so. The balm moisturizes the wood and gives a beautiful depth to the briar. I then buffed the stummel with a microfibre cloth.

I used all nine micromesh pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand the whole stummel. This sanding minimizes flaws in the briar and provides a beautiful smoothness to the wood. I rubbed some LBE Before & After Restoration Balm into the briar and let it sit for 30 minutes or so. The balm moisturizes the wood and gives a beautiful depth to the briar. I then buffed the stummel with a microfibre cloth.

For the final step, I took the pipe to my bench polisher and carefully buffed it – first with a blue diamond compound, then with three coats of carnauba wax. This procedure makes the pipe look its best – the stummel sings and the stem glows.

For the final step, I took the pipe to my bench polisher and carefully buffed it – first with a blue diamond compound, then with three coats of carnauba wax. This procedure makes the pipe look its best – the stummel sings and the stem glows.

All done! This Mark Tinsky Grecian Plateau Lovat looks fantastic again and is ready to be enjoyed by its next owner. I am pleased to announce that this pipe is for sale! If you are interested in acquiring it for your collection, please have a look in the ‘American’ section of the store here on Steve’s website. You can also email me directly at kenneth@knightsofthepipe.com. The approximate dimensions of the pipe are as follows: length 6½ in. (165 mm); height 2⅜ in. (60 mm); bowl diameter 1¾ in. (45 mm); chamber diameter 1 in. (25 mm). The weight of the pipe is 2¼ oz. (67 g). I hope you enjoyed reading the story of this pipe’s restoration as much as I enjoyed restoring it. If you are interested in more of my work, please follow me here on Steve’s website or send me an email. Thank you very much for reading and, as always, I welcome and encourage your comments.