Blog by Dal Stanton

My good friend in India, Paresh, commissioned 3 pipes from the ‘For “Pipe Dreamers” Only!’ collection. To have him commission pipes is a privilege after being with him and his family in India not long ago. I will not forget the hospitality that Paresh and Abha provided to me, Steve and Jeff when we all converged in Pune. Paresh has commissioned some pipes before and it’s no secret that he is drawn to large pipes. One of the three he chose is perhaps the largest pipe that I’ve ever handled, and it also offers a good bit of weightiness as it rests in the hand – note, I didn’t say, “palm”. This guy is for the hand! I took a picture of the three he commissioned to show the comparison with normal sized pipes – with the Kilimanjaro is a French CPF Chesterfield and a BBB Classic Chimney which are next in the queue. The dimensions of the Kilimanjaro are an impressive, Length: 7 inches, Height: 2 5/8 inches, Rim width: 1 1/2 inches, Chamber width: 1 inch, Chamber depth: 2 3/16 inches. Here are more pictures of the Kilimanjaro now on the worktable.

The dimensions of the Kilimanjaro are an impressive, Length: 7 inches, Height: 2 5/8 inches, Rim width: 1 1/2 inches, Chamber width: 1 inch, Chamber depth: 2 3/16 inches. Here are more pictures of the Kilimanjaro now on the worktable.

The nomenclature is on the lower shank panel with ‘KILIMANJARO’ to the immediate left of, ‘MADE IN TANGANYIKA’. To the fore of these stampings, almost on the heel of the stummel is the shape number of 104.

The nomenclature is on the lower shank panel with ‘KILIMANJARO’ to the immediate left of, ‘MADE IN TANGANYIKA’. To the fore of these stampings, almost on the heel of the stummel is the shape number of 104.

Pipedia has a good amount of information about this pipe’s provenance in the article about the Tanganyika Meerschaum Corporation:

From Pipes, Artisans and Trademarks, by José Manuel Lopes

Tanganyika Meerschaum Corporation is a company that formed in 1955 by Kenyan businessmen from Nairobi after the discovery of a meerschaum mine relatively close to the surface on Kilimanjaro. The meerschaum is tougher, less porous, and cheaper than the Turkish variety. Another mine was soon discovered in Sinya, in the famous Amboseli Game Park.

The company, previously based in Arusha (Tanzania), became an associate of a Belgium firm, but closed some years after. It produced the Caveman, Countryman, Kiko, Killimanjaro, Sportsman, Townsman, and Wiga brands. It maintained a link with GBD for the making of the GBD Block Meerschaum series, and after its closure, the English firms, London Meerschaum and Manx Pipes (Manx Meerschaum) continued producing with African meerschaum.

This additional information about the better-known subsidiary, Kiko, is from Pipedia’s ‘Kiko’ article:

Kiko, meaning “pipe” in Swahili-Kiswahili to English translation, is probably the best known of the various brands listed below . In East Africa Meerschaum is found in Tanganyika, once known as German East Africa, and since 1964 part of the United Republic of Tanzania. The main deposit comes from the Amboseli basin surrounding the Lake Amboseli. Tanganyika Meerschaum is normally stained in shades of brown, black and yellow, and is considered to be inferior to Meerschaum from Turkey. Even though, the raw material is mined by the Tanganyika Meerschaum Corporation and to a large extent used for pipe making.

The same Pipedia ‘Kiko’ article referenced the specific line of ‘Kilimanjaro’ as being an old brand from Amboseli Pipes that belonged to the parent Tanganyika Meerschaum Corporation and provided a picture of a Kilimanjaro sporting the designator for that line, a rhinoceros, which the Kilimanjaro on my worktable unfortunately shows no evidence of having survived its journey. The box that carried the Kilimanjaro in the picture is very cool! The description of the Kilimanjaro line also includes this interesting information: “East African pipewood Meerschaum lined and individually boxed. Available in black rough finish and natural smooth or rough finish.” The finish looks like a blasted finish, but I’m not sure if it is not also rusticated – perhaps it is a ‘blasticated’ finish – a combination of both, but either way, it’s an attractive, tactile surface. ‘Pipewood’ is the description above and I’m sure the wood is not briar. I find no ‘pipewood’ of African origin doing a quick search on the internet. So, it’s East African ‘Pipewood’ whatever that is.

The description of the Kilimanjaro line also includes this interesting information: “East African pipewood Meerschaum lined and individually boxed. Available in black rough finish and natural smooth or rough finish.” The finish looks like a blasted finish, but I’m not sure if it is not also rusticated – perhaps it is a ‘blasticated’ finish – a combination of both, but either way, it’s an attractive, tactile surface. ‘Pipewood’ is the description above and I’m sure the wood is not briar. I find no ‘pipewood’ of African origin doing a quick search on the internet. So, it’s East African ‘Pipewood’ whatever that is.

The issues facing this Kilimanjaro giant are significant. When Paresh commissioned this pipe with a full awareness of the issues it faces, said to me that he was not only attracted to the size, but he was also looking forward to seeing what I did to rescue this giant pipe! No pressure! To be sure, I’m not sure that the remedies I employ will provide a long-term resolution, but I’m hopeful. The first and fundamental issue is the vertical crack that runs for ‘miles’ along the left side of the pipewood bowl. The first picture below shows ‘daylight’ coming through the crack at the rim level.  The following pictures show the crack as it disappears into the ‘moon surface’ crags and crevasses of the pipewood finish. To find the terminus point of the crack will require a magnifying glass. The question that I ask myself is what caused the crack?

The following pictures show the crack as it disappears into the ‘moon surface’ crags and crevasses of the pipewood finish. To find the terminus point of the crack will require a magnifying glass. The question that I ask myself is what caused the crack?

The other major issue is the Meerschaum lining. The trauma, whatever the source was, cracked and broke off the upper part of the Meer-lining. The Meer breakage appears to correlate to the crack-side which would indicate that the crack and the Meer breakage go together. The question that comes to my mind again is, what caused the crack and the breakage? To ‘Sherlock’ the scene shows no trauma to the surrounding pipewood, which I would expect to see if the trauma were caused by a dropping of the pipe. Inspection of the rim leaves me with the impression that it is thin for the size of the pipe. This observation leads me to postulate that the crack was possibly caused by the expansion of the wood as the Meerschaum heated, but how much does Meerschaum expand as it heats? If so, even microscopically, this would suggest that the expansion could have contributed to the pressure on the encasing pipewood contributing to the crack. But what explains the breakage of the Meer? The vertical crack is set almost center between the widest break points of the Meerschaum.

The other major issue is the Meerschaum lining. The trauma, whatever the source was, cracked and broke off the upper part of the Meer-lining. The Meer breakage appears to correlate to the crack-side which would indicate that the crack and the Meer breakage go together. The question that comes to my mind again is, what caused the crack and the breakage? To ‘Sherlock’ the scene shows no trauma to the surrounding pipewood, which I would expect to see if the trauma were caused by a dropping of the pipe. Inspection of the rim leaves me with the impression that it is thin for the size of the pipe. This observation leads me to postulate that the crack was possibly caused by the expansion of the wood as the Meerschaum heated, but how much does Meerschaum expand as it heats? If so, even microscopically, this would suggest that the expansion could have contributed to the pressure on the encasing pipewood contributing to the crack. But what explains the breakage of the Meer? The vertical crack is set almost center between the widest break points of the Meerschaum.  This question prompted me to write Steve with the question regarding how a Meer-lining was installed. Was the Meer-lining a result of compacted or pressed Meerschaum that was formed to the chamber or was it a cut piece of Meerschaum that was inserted as a separate piece? Steve’s response was that Meer-linings generally were cut in a lathe and drilled and inserted to fit the chamber. This information was helpful because it would indicate then that the Meer-lining remaining in this Kilimanjaro was essentially one piece, and barring any large hidden cracks in the surviving Meer, should be structurally intact. I’ll need to clean the surviving Meerschaum lining to make sure that the rest is intact and then begin the repair from the outside working in. With this initial assessment of the serious issues standing in the way, I begin the clean-up by running pipe cleaners dipped in isopropyl 95% through the stem and then into a soak with Before & After Deoxidizer along with other pipes in the queue.

This question prompted me to write Steve with the question regarding how a Meer-lining was installed. Was the Meer-lining a result of compacted or pressed Meerschaum that was formed to the chamber or was it a cut piece of Meerschaum that was inserted as a separate piece? Steve’s response was that Meer-linings generally were cut in a lathe and drilled and inserted to fit the chamber. This information was helpful because it would indicate then that the Meer-lining remaining in this Kilimanjaro was essentially one piece, and barring any large hidden cracks in the surviving Meer, should be structurally intact. I’ll need to clean the surviving Meerschaum lining to make sure that the rest is intact and then begin the repair from the outside working in. With this initial assessment of the serious issues standing in the way, I begin the clean-up by running pipe cleaners dipped in isopropyl 95% through the stem and then into a soak with Before & After Deoxidizer along with other pipes in the queue.

After several hours in the soak, I extract the Kilimanjaro’s stem and run pipe cleaners dipped in isopropyl 95% to clear the Deoxidizer from the airway. I then wipe the stem down with cotton pads wetted with alcohol to remove the raised oxidation. I missed taking pictures of this part, but the aftermath shows residual oxidation in the stem after the Before & After Deoxidizer soak.

After several hours in the soak, I extract the Kilimanjaro’s stem and run pipe cleaners dipped in isopropyl 95% to clear the Deoxidizer from the airway. I then wipe the stem down with cotton pads wetted with alcohol to remove the raised oxidation. I missed taking pictures of this part, but the aftermath shows residual oxidation in the stem after the Before & After Deoxidizer soak. I follow by scrubbing the stem with Mr. Clean Magic Eraser to see if it would deep clean the oxidation. There is some additional improvement but, in the end, I’ll need to sand the stem to remove more oxidation.

I follow by scrubbing the stem with Mr. Clean Magic Eraser to see if it would deep clean the oxidation. There is some additional improvement but, in the end, I’ll need to sand the stem to remove more oxidation. At this point, I apply paraffin oil to the stem to hydrate and condition it. I open the aperture on the iPhone App and take another picture showing the deep oxidation that can still be detected. I put the stem aside for the time to look again at the stummel.

At this point, I apply paraffin oil to the stem to hydrate and condition it. I open the aperture on the iPhone App and take another picture showing the deep oxidation that can still be detected. I put the stem aside for the time to look again at the stummel. Before beginning on the stummel repair, I need to clean the Meerschaum lining to be able to get a closer look at its condition. I see something obstructing the draft hole. After unsuccessfully trying to push a pipe cleaner through the draft hole via the mortise, I take a dental probe and am able to pop it out. It appears to be an old hunk of dottle that had hardened.

Before beginning on the stummel repair, I need to clean the Meerschaum lining to be able to get a closer look at its condition. I see something obstructing the draft hole. After unsuccessfully trying to push a pipe cleaner through the draft hole via the mortise, I take a dental probe and am able to pop it out. It appears to be an old hunk of dottle that had hardened.  I take additional pictures of the chamber walls moving up to the rim where the Meerschaum breakage is. The floor of the chamber is clear of carbon buildup. This is the moment of truth for this pipe – to remove the carbon to examine the condition of the Meerschaum. If it has more substantial cracks underneath it could raise questions about the integrity of the remaining Meer and the wisdom of a repair, but we will see.

I take additional pictures of the chamber walls moving up to the rim where the Meerschaum breakage is. The floor of the chamber is clear of carbon buildup. This is the moment of truth for this pipe – to remove the carbon to examine the condition of the Meerschaum. If it has more substantial cracks underneath it could raise questions about the integrity of the remaining Meer and the wisdom of a repair, but we will see.

Patience is the key as I gingerly scrape the carbon layer off the remaining Meer surface. I use the Savinelli Fitsall Tool to do the scraping. I don’t work on it like I would a briar chamber. This scraping is more akin to rubbing with the edge to dislodge the buildup.

Patience is the key as I gingerly scrape the carbon layer off the remaining Meer surface. I use the Savinelli Fitsall Tool to do the scraping. I don’t work on it like I would a briar chamber. This scraping is more akin to rubbing with the edge to dislodge the buildup. After the scraping, I use 240 grade sanding paper wrapped around a Sharpie Pen to reach down into the huge chamber to continue to clean.

After the scraping, I use 240 grade sanding paper wrapped around a Sharpie Pen to reach down into the huge chamber to continue to clean. When I’ve sanded sufficiently, I give the chamber a wipe with a cotton pad wetted with isopropyl 95% to remove left over carbon dust.

When I’ve sanded sufficiently, I give the chamber a wipe with a cotton pad wetted with isopropyl 95% to remove left over carbon dust. With the carbon layer cleared and the Meer surface exposed, I find an almost perfectly uniform hairline crack, which almost looks like a seam, halfway down the chamber running in a full circle around the circumference of the chamber. It is so uniform that it looks like the Meerschaum was constructed in halves – a lower half bowl and the upper half ring.

With the carbon layer cleared and the Meer surface exposed, I find an almost perfectly uniform hairline crack, which almost looks like a seam, halfway down the chamber running in a full circle around the circumference of the chamber. It is so uniform that it looks like the Meerschaum was constructed in halves – a lower half bowl and the upper half ring.  I also detect another hairline originating at the uniform crack running downwardly and then curving as it nears the floor. The good news, if there’s good news to be had, is that these are tight hairline cracks, there’s no crumbling. The Meerschaum below the rim seems to be solid. To the touch, the hairlines are imperceptible. With a sharp dental probe, I was able to detect a slight bump as I drew the point across the hairlines.

I also detect another hairline originating at the uniform crack running downwardly and then curving as it nears the floor. The good news, if there’s good news to be had, is that these are tight hairline cracks, there’s no crumbling. The Meerschaum below the rim seems to be solid. To the touch, the hairlines are imperceptible. With a sharp dental probe, I was able to detect a slight bump as I drew the point across the hairlines.  I’ve already decided what I will do. I’ve been waiting some time for this Meer-lined repair to come to the top of the queue. I want to give this Kilimanjaro a shot at continuing to serve. I worked on a previous Meer-lining repair of a Zulu (see: An Italian Croc-skin Zulu and a Bear of a Meer-Lining Repair) where I discovered an old timers’ approach to addressing Meerschaum problems. In the Zulu repair, Steve told me about Troy’s approach on Baccy Pipes. Troy’s method of using chalk and egg whites to repair Meer surfaces worked with the Zulu and I had this in mind from the beginning looking at the Kilimanjaro’s issues. Steve had reposted Troy’s blog on the methodology, and I had saved it as a keeper in my resource bucket. Steve’s repost can be found here: Old Time Meer Lining Repair Method On a Kaywoodie Shellcraft #5651 | Baccy Pipes which will then take you over to Troy’s site. Troy’s mixture of egg white and chalk is an amazing Meer-looking and feeling composite which holds up very well. Troy’s approach of patient, layering of the mixture fills and reinforces the existing Meerschaum. I’m looking forward to seeing what it will do again, but first, I must address the daunting ‘pipewood’ crack running down the side of the bowl. This is critical to reestablish a solid ‘frame’ around the Meerschaum. I take a few fresh pictures of this ‘Grand Crack Canyon’ which runs down and disappears in the lower craggy regions – everything about this pipe is BIG! You can see ‘day-light’ at the upper, rim-part of the crack.

I’ve already decided what I will do. I’ve been waiting some time for this Meer-lined repair to come to the top of the queue. I want to give this Kilimanjaro a shot at continuing to serve. I worked on a previous Meer-lining repair of a Zulu (see: An Italian Croc-skin Zulu and a Bear of a Meer-Lining Repair) where I discovered an old timers’ approach to addressing Meerschaum problems. In the Zulu repair, Steve told me about Troy’s approach on Baccy Pipes. Troy’s method of using chalk and egg whites to repair Meer surfaces worked with the Zulu and I had this in mind from the beginning looking at the Kilimanjaro’s issues. Steve had reposted Troy’s blog on the methodology, and I had saved it as a keeper in my resource bucket. Steve’s repost can be found here: Old Time Meer Lining Repair Method On a Kaywoodie Shellcraft #5651 | Baccy Pipes which will then take you over to Troy’s site. Troy’s mixture of egg white and chalk is an amazing Meer-looking and feeling composite which holds up very well. Troy’s approach of patient, layering of the mixture fills and reinforces the existing Meerschaum. I’m looking forward to seeing what it will do again, but first, I must address the daunting ‘pipewood’ crack running down the side of the bowl. This is critical to reestablish a solid ‘frame’ around the Meerschaum. I take a few fresh pictures of this ‘Grand Crack Canyon’ which runs down and disappears in the lower craggy regions – everything about this pipe is BIG! You can see ‘day-light’ at the upper, rim-part of the crack.

I don’t know with certainty the reason for the crack and the Meer breakage, but my best guess is that it was heating expansion. If this is correct, the good news is that the bowl has expanded causing the crack. Theoretically, this should be good news for the repair of the crack, filling it at this expanded point will provide a better framework for the Meerschaum and overall stability of the pipe – theoretically. Even though the crack and the Meerschaum repairs are large undertakings, the current condition of the Kilimanjaro Giant makes it unusable, and so there’s absolutely nothing to lose for this big guy. He’s already in the ICU! If after the repairs are completed, and if Paresh decides he doesn’t want him, he can convalesce in my racks for as long as he wishes 😊.

I don’t know with certainty the reason for the crack and the Meer breakage, but my best guess is that it was heating expansion. If this is correct, the good news is that the bowl has expanded causing the crack. Theoretically, this should be good news for the repair of the crack, filling it at this expanded point will provide a better framework for the Meerschaum and overall stability of the pipe – theoretically. Even though the crack and the Meerschaum repairs are large undertakings, the current condition of the Kilimanjaro Giant makes it unusable, and so there’s absolutely nothing to lose for this big guy. He’s already in the ICU! If after the repairs are completed, and if Paresh decides he doesn’t want him, he can convalesce in my racks for as long as he wishes 😊.

I decide to do this repair before cleaning the stummel in the normal order of things, but I didn’t want to dampen the pipewood in the crack or mess with the Meerschaum butting up to the crack. The first order of business is to identify and mark the lower termination point of the crack. This is critical to keep the crack from growing through the southern pole of the bowl. Taking a magnifying glass, I follow the crack until I find the endpoint and I use a sharp dental probe to mark that spot. This helps me to find it again as well as to help guide the 1mm drill bit when I drill a counter-creep hole. I take a very close-up picture of the inverted stummel to show the difficulty of tracing the crack as it becomes less distinct and blends into the moon-scape cragginess. I mark the crack and circle what appears to be the end of the crack. Again, I recheck with the magnifying glass and then mark the point with the sharp dental probe. I then mount the 1mm drill bit onto the Dremel and with nerves of steel, drill a hole freehand! It’s amazing how shaky the hand gets when you’re trying to do precision drilling. I intentionally make the counter-creep hole a little bigger than usual to make sure the crack is arrested. I have no worries about blending in the rough blasted surface.

Again, I recheck with the magnifying glass and then mark the point with the sharp dental probe. I then mount the 1mm drill bit onto the Dremel and with nerves of steel, drill a hole freehand! It’s amazing how shaky the hand gets when you’re trying to do precision drilling. I intentionally make the counter-creep hole a little bigger than usual to make sure the crack is arrested. I have no worries about blending in the rough blasted surface.

Before applying thin CA glue, I use a Sharpie Pen to darken the hole I just drilled. This will help blending after I apply the clear CA glue.

Before applying thin CA glue, I use a Sharpie Pen to darken the hole I just drilled. This will help blending after I apply the clear CA glue. Next, I use the thinnest CA glue in my inventory with a precision nozzle on it. I use thin CA glue to maximize the seepage of glue deeply into the crack. I don’t want the glue congealing on the surface but curing deeply in the pipewood crack to reinforce the strength. After waiting a while, I apply another line of CA down the crack. I also apply CA to the inside of the rim where the crack is exposed above the Meerschaum.

Next, I use the thinnest CA glue in my inventory with a precision nozzle on it. I use thin CA glue to maximize the seepage of glue deeply into the crack. I don’t want the glue congealing on the surface but curing deeply in the pipewood crack to reinforce the strength. After waiting a while, I apply another line of CA down the crack. I also apply CA to the inside of the rim where the crack is exposed above the Meerschaum.

While I apply additional coats of CA glue to the stummel crack repair and the CA glue cures, I switch focus to the stem. Even after soaking in the Before & After Deoxidizer, the oxidation in the stem is significant as the pictures show. On the first picture, the saddle has a round section where the vulcanite appears burnt or something – like a wart almost. I move directly to sanding the entire stem with 240 grade paper to remove the oxidation.

While I apply additional coats of CA glue to the stummel crack repair and the CA glue cures, I switch focus to the stem. Even after soaking in the Before & After Deoxidizer, the oxidation in the stem is significant as the pictures show. On the first picture, the saddle has a round section where the vulcanite appears burnt or something – like a wart almost. I move directly to sanding the entire stem with 240 grade paper to remove the oxidation. To guard against shouldering the saddle stem’s shank facing I employ a disc that I fashioned to keep the sanding in check.

To guard against shouldering the saddle stem’s shank facing I employ a disc that I fashioned to keep the sanding in check.

After the first round of sanding with 240 grade paper I follow by wet sanding using 600 grade paper. On the dark surface it’s easier to take pictures that show the oxidation holding on. The second picture shows a close-up of the ‘wart’ after sanding. It shows pitting and even after sanding, the area appears rough and clouded.

After the first round of sanding with 240 grade paper I follow by wet sanding using 600 grade paper. On the dark surface it’s easier to take pictures that show the oxidation holding on. The second picture shows a close-up of the ‘wart’ after sanding. It shows pitting and even after sanding, the area appears rough and clouded.

I return to sanding with 240 grade paper on the areas that continue to show oxidation and then finally move on to wet sanding with 600 grade paper and then apply 000 steel wool. I also use Mr. Clean Magic Eraser to clean further. The stem is much improved even though the ‘wart’ is still visible.

I return to sanding with 240 grade paper on the areas that continue to show oxidation and then finally move on to wet sanding with 600 grade paper and then apply 000 steel wool. I also use Mr. Clean Magic Eraser to clean further. The stem is much improved even though the ‘wart’ is still visible.

I then apply Before & After Fine and Extra Fine Polish to further clean and condition the vulcanite stem. In succession I apply the polishes with my fingers and rub them in. Between each coat, I allow some time – about 10 minutes, for the polish to absorb. I then wipe the stem clean using paper towels and then buff some with a microfiber cloth and put the stem aside.

I then apply Before & After Fine and Extra Fine Polish to further clean and condition the vulcanite stem. In succession I apply the polishes with my fingers and rub them in. Between each coat, I allow some time – about 10 minutes, for the polish to absorb. I then wipe the stem clean using paper towels and then buff some with a microfiber cloth and put the stem aside. After applying several applications of thin CA glue to the stummel crack, the crack is filled, and the glue cured. To blend the ‘glue line’ I take a cotton bud and dip it in acetone and rub it over the glue line. This removes much of the excess CA glue on the surface running along the crack line while not bothering the glue in the crack itself. Doing this helps blend the crack in the craggy stummel surface. I’m pleased with this crack repair and where I used acetone to clean, the hue of the pipewood is somewhat lightened. I’ll address this later.

After applying several applications of thin CA glue to the stummel crack, the crack is filled, and the glue cured. To blend the ‘glue line’ I take a cotton bud and dip it in acetone and rub it over the glue line. This removes much of the excess CA glue on the surface running along the crack line while not bothering the glue in the crack itself. Doing this helps blend the crack in the craggy stummel surface. I’m pleased with this crack repair and where I used acetone to clean, the hue of the pipewood is somewhat lightened. I’ll address this later.

With the stummel crack now stabilized, and before working on the Meerschaum lining patch project, I continue with the normal cleaning regimen. I would rather finish with a clean pipe and not have to clean it at the end! The stummel surface is dirty and grimy. Now that the crack is repaired, I’m looking at the stummel surface and I see hints of oxblood coloring. Using undiluted Murphy, I scrub the blasted surface with a bristled toothbrush. I scrub well getting into the crags of the blasting.

With the stummel crack now stabilized, and before working on the Meerschaum lining patch project, I continue with the normal cleaning regimen. I would rather finish with a clean pipe and not have to clean it at the end! The stummel surface is dirty and grimy. Now that the crack is repaired, I’m looking at the stummel surface and I see hints of oxblood coloring. Using undiluted Murphy, I scrub the blasted surface with a bristled toothbrush. I scrub well getting into the crags of the blasting.

After cleaning the external surface, I go to work on the internals. Using pipe cleaners – bristled and soft and cotton buds dipped in isopropyl 95%, I work on the mortise. I also employ shank brushes and a small dental scoop to help clean. I’m not able to reach far into the mortise with the dental tool because the threaded mortise narrows. I discover that the mortise threading is cut into the wood. I thought at first that it would be metal like the threaded tenon, but the threads are hewn out of the mortise. I’m careful not to wear them down through the cleaning. After some time and effort, the pipe cleaners start emerging lighter and I move on.

After cleaning the external surface, I go to work on the internals. Using pipe cleaners – bristled and soft and cotton buds dipped in isopropyl 95%, I work on the mortise. I also employ shank brushes and a small dental scoop to help clean. I’m not able to reach far into the mortise with the dental tool because the threaded mortise narrows. I discover that the mortise threading is cut into the wood. I thought at first that it would be metal like the threaded tenon, but the threads are hewn out of the mortise. I’m careful not to wear them down through the cleaning. After some time and effort, the pipe cleaners start emerging lighter and I move on. I’m getting ready to head to the Black Sea for a few days on the beach with my wife for some R&R from our work here in Sofia. Before putting the stummel aside, I apply paraffin oil to the pipewood to help rehydrate the blasted or perhaps, blasticated pipewood. It looks good and gives me a sneak peak of what the bowl will look like in the later stages of the restoration – I like what I see!

I’m getting ready to head to the Black Sea for a few days on the beach with my wife for some R&R from our work here in Sofia. Before putting the stummel aside, I apply paraffin oil to the pipewood to help rehydrate the blasted or perhaps, blasticated pipewood. It looks good and gives me a sneak peak of what the bowl will look like in the later stages of the restoration – I like what I see! The time was wonderful, the beach was superb and I’m thankful for the time of R&R with my lovely bride. We enjoy the Black Sea immensely and find the slower pace rejuvenating to the soul. I took along with me the newest addition to my collection that I purchased in a trip to Istanbul a few weeks ago.

The time was wonderful, the beach was superb and I’m thankful for the time of R&R with my lovely bride. We enjoy the Black Sea immensely and find the slower pace rejuvenating to the soul. I took along with me the newest addition to my collection that I purchased in a trip to Istanbul a few weeks ago.  I love this carved block Altinay Meerschaum sculpted Billiard with the burgundy acrylic silver banded stem. I looked at 100s of carved Meerschaums at the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul, but this was the pipe that called my name and chose me 😊. I guess I’m a ‘classic shape’ pipe man at heart.

I love this carved block Altinay Meerschaum sculpted Billiard with the burgundy acrylic silver banded stem. I looked at 100s of carved Meerschaums at the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul, but this was the pipe that called my name and chose me 😊. I guess I’m a ‘classic shape’ pipe man at heart. While on the beach, I thought a lot about how to approach the next step in this gargantuan Meer-lined Kilimanjaro. The method I will be using to repair the Meerschaum I discovered from Troy (of Baccy Pipes) who posted this methodology on his website: Old Time Meer Lining Repair Method on a 1930s Kaywoodie Shellcraft #5651 described in his blog how he came upon this strategy as he approached repairing his first Meer lining:

While on the beach, I thought a lot about how to approach the next step in this gargantuan Meer-lined Kilimanjaro. The method I will be using to repair the Meerschaum I discovered from Troy (of Baccy Pipes) who posted this methodology on his website: Old Time Meer Lining Repair Method on a 1930s Kaywoodie Shellcraft #5651 described in his blog how he came upon this strategy as he approached repairing his first Meer lining:

I had read and heard from other pipe restores that an old late 19th-early 20th century druggist recipe for fixing broken meerschaum was egg whites and finely ground chalk, so that was what I was going to try and fix the meerlined rim with. It is said to have about the same porous properties of meerschaum and imparts no taste to the tobacco.

Troy also affirms in the comments section on his blog that the mixture of egg white and chalk is ‘neutral’ and presents no difference in aftertaste compared to native Meerschaum. I used this methodology with great success in the restoration An Italian Croc Skin Zulu and a Bear of a Meer Lining Repair. This Zulu came out well. I want to state for the record: the Meerschaum is NOT being repaired but emulated. The process reinforces and strengthens the faults of the Meerschaum as well as masking the problems. When I did the Zulu repair, I was taken to task by a commenter that it wasn’t a Meer repair…. True indeed. But the alternative in this case will be that the pipe is never used again. The method is without doubt a patch to the existing native Meerschaum, but with no better alternative, I’m willing to go with it.

To begin, I take a picture looking at the rim-top and the upper condition of the Meer. I use a piece of 240 grade paper and lightly sand the top side of the Meerschaum to clean it and to show better the imperfections. I also do a quick sanding over the internal pipewood that is exposed.  I follow Troy’s lead in masking the stummel to protect it from the chalk/egg white mixture because it sets up very hard – not something I want on the Kilimanjaro’s blasted surface!

I follow Troy’s lead in masking the stummel to protect it from the chalk/egg white mixture because it sets up very hard – not something I want on the Kilimanjaro’s blasted surface!  With the Zulu repair I found some chalk from a Kindergarten teacher (of course) who is a fellow team member here in Bulgaria. I used the old-fashioned way of pulverizing the chalk as finely as I could with the mortar and pestle to do the job.

With the Zulu repair I found some chalk from a Kindergarten teacher (of course) who is a fellow team member here in Bulgaria. I used the old-fashioned way of pulverizing the chalk as finely as I could with the mortar and pestle to do the job.  After putting a pipe cleaner in the airway and through the draft hole to keep it free of ‘Ole Timer’ mixture, I apply an initial thin coating of the mixture using my finger to fill in the cracks in the fire chamber and over the broken area at the rim – filling the gaps and cracks is important at the beginning. Later after this first, thin coat sets, I will build up the lining toward the rim so that it will cover the cracks as well as provide a uniform surface as I build out the rim breakage. For the first application, I mix 1 egg white to about 3 tablespoons of chalk to create the initial mixture to get into and fill the cracks for the first two applications. I save the remaining mixture and put it in the fridge and put the stummel aside for several hours for the ‘Ole Timer’ mixture to set. The key to Troy’s approach, I believe, is the patient layering of the mixture allowing it to set and build, layer by layer – not putting the mixture on too thick which I believe would be more prone to trapping air pockets and cracking. The pictures show the process.

After putting a pipe cleaner in the airway and through the draft hole to keep it free of ‘Ole Timer’ mixture, I apply an initial thin coating of the mixture using my finger to fill in the cracks in the fire chamber and over the broken area at the rim – filling the gaps and cracks is important at the beginning. Later after this first, thin coat sets, I will build up the lining toward the rim so that it will cover the cracks as well as provide a uniform surface as I build out the rim breakage. For the first application, I mix 1 egg white to about 3 tablespoons of chalk to create the initial mixture to get into and fill the cracks for the first two applications. I save the remaining mixture and put it in the fridge and put the stummel aside for several hours for the ‘Ole Timer’ mixture to set. The key to Troy’s approach, I believe, is the patient layering of the mixture allowing it to set and build, layer by layer – not putting the mixture on too thick which I believe would be more prone to trapping air pockets and cracking. The pictures show the process.

After a few more hours, the first picture shows the state of the Ole Timer mix. With my finger, I again add a coat of the mixture to the chamber and let it set for several hours for it to set up, dry and harden more.

After a few more hours, the first picture shows the state of the Ole Timer mix. With my finger, I again add a coat of the mixture to the chamber and let it set for several hours for it to set up, dry and harden more.

After several hours, the layering is taking hold.

After several hours, the layering is taking hold. I add another tablespoon of chalk to the current thin mixture to thicken it some. Again, using my finger, I add another coat to the chamber, rim and over the breakage area. This time I let the application cure overnight.

I add another tablespoon of chalk to the current thin mixture to thicken it some. Again, using my finger, I add another coat to the chamber, rim and over the breakage area. This time I let the application cure overnight.

The next morning, I take another picture to show the progress.

The next morning, I take another picture to show the progress.  I add one additional coating of the Ole Timer mixture to the entire chamber at the current thickness. Again, I let it set for a few hours for it to dry and harden.

I add one additional coating of the Ole Timer mixture to the entire chamber at the current thickness. Again, I let it set for a few hours for it to dry and harden.

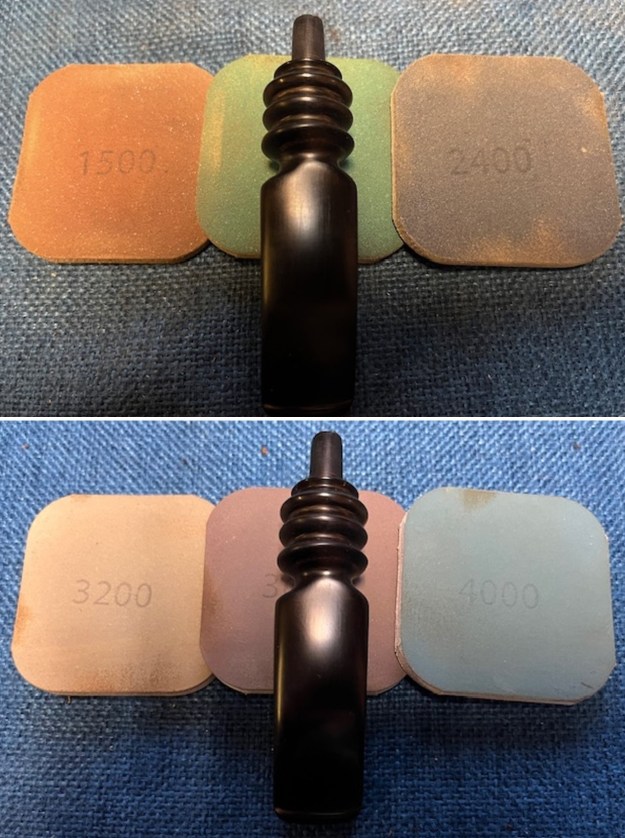

With the stummel on the side again, I turn to the stem and apply the full regimen of nine micromesh pads. I begin by wet sanding with pads 1500 to 2400, then dry sand with pads 3200 to 4000 and 6000 to 12000. Between each set of three pads, I apply a coat of Obsidian Oil to continue rejuvenating the vulcanite stem. It looks good!

With the stummel on the side again, I turn to the stem and apply the full regimen of nine micromesh pads. I begin by wet sanding with pads 1500 to 2400, then dry sand with pads 3200 to 4000 and 6000 to 12000. Between each set of three pads, I apply a coat of Obsidian Oil to continue rejuvenating the vulcanite stem. It looks good!

Now it’s time to work directly on the main Meerschaum breakage on the rim. I’ve built the layering over the exposed area with the previous coats of the Ole Timer mix of chalk and egg whites. I separate a smaller portion of the remaining mixture in a container and again add more powdered chalk to thicken it a bit more. When it seems about the right viscosity to stand more firmly in the break cavity, I apply the mixture to the rim. I keep the stummel on its side, with the breakage on the bottom to use gravity to settle the mixture in the break cavity. I first take a before picture then an after. I don’t want to ‘over’ fill but allow more time to apply an additional coat of the thicker mixture. I again put the stummel aside for several hours for the thicker mixture to dry and harden. Again, I put all the Ole Timer mix back into the fridge to use again.

Now it’s time to work directly on the main Meerschaum breakage on the rim. I’ve built the layering over the exposed area with the previous coats of the Ole Timer mix of chalk and egg whites. I separate a smaller portion of the remaining mixture in a container and again add more powdered chalk to thicken it a bit more. When it seems about the right viscosity to stand more firmly in the break cavity, I apply the mixture to the rim. I keep the stummel on its side, with the breakage on the bottom to use gravity to settle the mixture in the break cavity. I first take a before picture then an after. I don’t want to ‘over’ fill but allow more time to apply an additional coat of the thicker mixture. I again put the stummel aside for several hours for the thicker mixture to dry and harden. Again, I put all the Ole Timer mix back into the fridge to use again.

Suffice it to say, I did several more coatings using the Old Timer mixture to build up the rim – I’m passing on more pictures of this process! My goal was to build out the chamber wall to the rim and to fill out the rim, including the breakage gap, so that the chamber is a uniform cylinder. From this reestablished uniform platform, I will then sand back to the original Meerschaum wall and reshape the rim to hopefully mask the breakage and produce an attractive rim presentation of darker pipewood meeting the new reinforced and repaired lining. That “meeting” to me is what makes Meer-lined pipes attractive – the contrasting themes of color and texture. The picture is the final after curing through the night to fully dry and harden.

Suffice it to say, I did several more coatings using the Old Timer mixture to build up the rim – I’m passing on more pictures of this process! My goal was to build out the chamber wall to the rim and to fill out the rim, including the breakage gap, so that the chamber is a uniform cylinder. From this reestablished uniform platform, I will then sand back to the original Meerschaum wall and reshape the rim to hopefully mask the breakage and produce an attractive rim presentation of darker pipewood meeting the new reinforced and repaired lining. That “meeting” to me is what makes Meer-lined pipes attractive – the contrasting themes of color and texture. The picture is the final after curing through the night to fully dry and harden.  I start sanding the top of the stummel by removing the excess Old Timer mix to bring it down to the masking tape level. I do this patiently to have a gradual approach to the rim surface. At this point, I’m careful to guard the internal repair to make sure I leave room for shaping the repaired rim. Fine tuning comes later. To be sure, working with this material is not tidy! The dried mixture is extremely strong and durable, but it makes for a very dusty work space especially in the sanding phase.

I start sanding the top of the stummel by removing the excess Old Timer mix to bring it down to the masking tape level. I do this patiently to have a gradual approach to the rim surface. At this point, I’m careful to guard the internal repair to make sure I leave room for shaping the repaired rim. Fine tuning comes later. To be sure, working with this material is not tidy! The dried mixture is extremely strong and durable, but it makes for a very dusty work space especially in the sanding phase. The masking tape is now showing through letting me know I’m down to the ‘show me the money’ area of the rim. It shows me how much depth exists in the repaired lining and it shows me if I’m possibly too thin. I’m wondering this when I look at the exact bottom of the picture – which represents the right-most edge of the Meer breakage. The edge of the fill dips in there. I decide to move on and see how things shape up.

The masking tape is now showing through letting me know I’m down to the ‘show me the money’ area of the rim. It shows me how much depth exists in the repaired lining and it shows me if I’m possibly too thin. I’m wondering this when I look at the exact bottom of the picture – which represents the right-most edge of the Meer breakage. The edge of the fill dips in there. I decide to move on and see how things shape up. I transition to sanding from the bottom of the chamber working up toward the rim. I wrap a piece of 240 grade paper around a Sharpie pen for reach. My aim is to clean out the floor of the chamber and sand a smooth transition from the Meer floor moving upward toward the Old Timer material surface.

I transition to sanding from the bottom of the chamber working up toward the rim. I wrap a piece of 240 grade paper around a Sharpie pen for reach. My aim is to clean out the floor of the chamber and sand a smooth transition from the Meer floor moving upward toward the Old Timer material surface. Well, it was going so well until it wasn’t. One of the things that I learned when I first started restoring pipes is that learning from what doesn’t work is as valuable as what does. As I sand, I see the cracks emerge in the Old Timer surface. When I first see that a major problem was in progress, two things come to my mind – this Kilimanjaro has perhaps transitioned from a commission benefitting the Daughters of Bulgaria (sorry Paresh!) to a personal project. The second was to continue sanding to see what remained intact.

Well, it was going so well until it wasn’t. One of the things that I learned when I first started restoring pipes is that learning from what doesn’t work is as valuable as what does. As I sand, I see the cracks emerge in the Old Timer surface. When I first see that a major problem was in progress, two things come to my mind – this Kilimanjaro has perhaps transitioned from a commission benefitting the Daughters of Bulgaria (sorry Paresh!) to a personal project. The second was to continue sanding to see what remained intact.

When the cracked sections started forming, I also use a sharp dental probe to aid the controlled destruction.

When the cracked sections started forming, I also use a sharp dental probe to aid the controlled destruction. As the following pictures show, the surprising part is that the current problems with the Ole Timer surface isn’t with the area of the major Meer breakage gap, but along the rim where the Meer has deteriorated and there was little for the Ole Timer mixture to grip.

As the following pictures show, the surprising part is that the current problems with the Ole Timer surface isn’t with the area of the major Meer breakage gap, but along the rim where the Meer has deteriorated and there was little for the Ole Timer mixture to grip.

When there isn’t anything to lose but time, I decide to proceed to see what can be done. My wife actually proposed the present path when I showed her the meltdown and explained that it was the thin deteriorating Meer at the top of the rim that the Ole Timer mix was not able to adhere. Her suggestion was to top the stummel to mine down to a healthier and more solid foundation for the rim. This sounded like a good option to me and perhaps would have been the better path at the beginning to clean out the deteriorated area more. Of course, there is no telling how the rest of the rim, Meer and Ole Timer surface will like this idea. To prepare for the topping adventure, I remove the masking tape from the top of the stummel.

When there isn’t anything to lose but time, I decide to proceed to see what can be done. My wife actually proposed the present path when I showed her the meltdown and explained that it was the thin deteriorating Meer at the top of the rim that the Ole Timer mix was not able to adhere. Her suggestion was to top the stummel to mine down to a healthier and more solid foundation for the rim. This sounded like a good option to me and perhaps would have been the better path at the beginning to clean out the deteriorated area more. Of course, there is no telling how the rest of the rim, Meer and Ole Timer surface will like this idea. To prepare for the topping adventure, I remove the masking tape from the top of the stummel. Using 240 grade paper on the chopping board, I very gently begin the topping process. At first I’m not sure what will result.

Using 240 grade paper on the chopping board, I very gently begin the topping process. At first I’m not sure what will result.  After a few rotations, I check the progress and the remaining Ole Timer mixture appears to be solid. This emboldens me and I continue to rotate the stummel several more rotations.

After a few rotations, I check the progress and the remaining Ole Timer mixture appears to be solid. This emboldens me and I continue to rotate the stummel several more rotations. Very interestingly, I the grain of the pipewood emerges during the topping. After several rotations, the emerging wood is not smooth like briar, but a naturally ‘rusticated looking’ presentation appears as the pictures below show very clearly. I continue to top the stummel and the pictures following show the gradually change in the appearance of the rim as the sanding does its work.

Very interestingly, I the grain of the pipewood emerges during the topping. After several rotations, the emerging wood is not smooth like briar, but a naturally ‘rusticated looking’ presentation appears as the pictures below show very clearly. I continue to top the stummel and the pictures following show the gradually change in the appearance of the rim as the sanding does its work.

The mysterious ‘pipewood’ continues to dog me. What is pipewood anyway? I did a bit of snooping in my research bucket and remembered that Charles Lemon had worked on a Kilimanjaro (see: Resurrecting a Giant Kilimanjaro War Club Billiard) and he had raised the same question about the type of wood he was working on – definitely not briar. In the comments section of that blog we went back and forth about the wood and Johan came up with the mysterious ‘Pipewood’ designation in Pipedia’s article which I referenced above. Charles didn’t resolve what ‘pipewood’ actually was either. I decided to ask my wife what she made of this ‘East African Pipewood’. She’s pretty amazing with plants and is a horticulturalist hobbiest in her own right. She looked at the grain I had uncovered on the rim and with little thought observed that that it looked like bamboo. With her curiosity piqued, she did a bit of online research and sent me a link with a picture (see LINK) labeled, ‘bamboo end grain flooring’. The cheetah-like spotting is very much like the Kilimanjaro’s rim. Then, a little later, as if to produce exhibit “2”, my wife handed me one of our throw-away bamboo chopsticks we get from our favorite Bulgarian Chinese home delivery restaurant. I managed to take a closely focused picture again to show the uniformed ‘tubular’ grain structure of a bamboo specimen. The case for East African Pipewood being some strain of bamboo is looking pretty strong. As Charles remarked in his blog noted above, whatever the wood is, it would not be good to use in direct contact with fire, like with briar, but would of necessity need to be paired with a Meershaum lining to work. Thanks to my gifted wife, I think I have a better handle on what pipewood actually is. What I’m seeing on the rim is a cross-section cut of this wood. The LONG crack down the side of the stummel makes more sense with the straightness of it – this wood it structured in long, straight grains. It would not, therefore, have a lot of resistance to an expansion from heating… it would seem! Curiosity satisfied, I move on.

The mysterious ‘pipewood’ continues to dog me. What is pipewood anyway? I did a bit of snooping in my research bucket and remembered that Charles Lemon had worked on a Kilimanjaro (see: Resurrecting a Giant Kilimanjaro War Club Billiard) and he had raised the same question about the type of wood he was working on – definitely not briar. In the comments section of that blog we went back and forth about the wood and Johan came up with the mysterious ‘Pipewood’ designation in Pipedia’s article which I referenced above. Charles didn’t resolve what ‘pipewood’ actually was either. I decided to ask my wife what she made of this ‘East African Pipewood’. She’s pretty amazing with plants and is a horticulturalist hobbiest in her own right. She looked at the grain I had uncovered on the rim and with little thought observed that that it looked like bamboo. With her curiosity piqued, she did a bit of online research and sent me a link with a picture (see LINK) labeled, ‘bamboo end grain flooring’. The cheetah-like spotting is very much like the Kilimanjaro’s rim. Then, a little later, as if to produce exhibit “2”, my wife handed me one of our throw-away bamboo chopsticks we get from our favorite Bulgarian Chinese home delivery restaurant. I managed to take a closely focused picture again to show the uniformed ‘tubular’ grain structure of a bamboo specimen. The case for East African Pipewood being some strain of bamboo is looking pretty strong. As Charles remarked in his blog noted above, whatever the wood is, it would not be good to use in direct contact with fire, like with briar, but would of necessity need to be paired with a Meershaum lining to work. Thanks to my gifted wife, I think I have a better handle on what pipewood actually is. What I’m seeing on the rim is a cross-section cut of this wood. The LONG crack down the side of the stummel makes more sense with the straightness of it – this wood it structured in long, straight grains. It would not, therefore, have a lot of resistance to an expansion from heating… it would seem! Curiosity satisfied, I move on. At this point I’ve come to a place where more topping will not help. The deteriorated and crumbling part or the rim and Meerschaum has been removed and solid Meer has emerged. I circle the one place that the Meer shows a residual chip. To remove this area would require more ‘Pipewood’ to be sacrificed than I’m willing to give.

At this point I’ve come to a place where more topping will not help. The deteriorated and crumbling part or the rim and Meerschaum has been removed and solid Meer has emerged. I circle the one place that the Meer shows a residual chip. To remove this area would require more ‘Pipewood’ to be sacrificed than I’m willing to give.  This next pictures shows clearly the depth of the Meer chip and how much of the top would need to be removed to erase the chip – not an option. As I look at the integrity of the remaining Old Timer faux Meer material, it appears to be strong but aesthetically, not very pretty! At this point, strength wins over pretty! With nothing to lose, I will again apply more coats of the Ole Timer mixture to fill this area and hopefully to solidify a stronger foundation.

This next pictures shows clearly the depth of the Meer chip and how much of the top would need to be removed to erase the chip – not an option. As I look at the integrity of the remaining Old Timer faux Meer material, it appears to be strong but aesthetically, not very pretty! At this point, strength wins over pretty! With nothing to lose, I will again apply more coats of the Ole Timer mixture to fill this area and hopefully to solidify a stronger foundation. I give the area a quick cleaning with a cotton bud dipped in alcohol.

I give the area a quick cleaning with a cotton bud dipped in alcohol. Again, I apply the mixture of egg white and chalk – applying several coats over a few days gradually to build up the area arriving at the point to start sanding again. I’m amazed that as often as I’ve gone back to my original mixture of egg white and chalk, it has only taken one egg white and it has done quite well being refrigerated after each application.

Again, I apply the mixture of egg white and chalk – applying several coats over a few days gradually to build up the area arriving at the point to start sanding again. I’m amazed that as often as I’ve gone back to my original mixture of egg white and chalk, it has only taken one egg white and it has done quite well being refrigerated after each application. I come to the point of sanding once more. The gradual building of the Ole Timer mix looks good. I use 240 grade paper wrapped around a Sharpie Pen to provide the firm backing to the sanding. I want the chamber straight and I don’t want to inadvertently bevel off the internal edge at the rim.

I come to the point of sanding once more. The gradual building of the Ole Timer mix looks good. I use 240 grade paper wrapped around a Sharpie Pen to provide the firm backing to the sanding. I want the chamber straight and I don’t want to inadvertently bevel off the internal edge at the rim.

I then take the stummel back to the topping board using 240 grade paper. This does a good job cleaning the rim surface again exposing the unique cheetah-like grain pattern of the pipewood.

I then take the stummel back to the topping board using 240 grade paper. This does a good job cleaning the rim surface again exposing the unique cheetah-like grain pattern of the pipewood.  I follow the 240 grade paper by rotating the stummel a few more times on 600 grade paper.

I follow the 240 grade paper by rotating the stummel a few more times on 600 grade paper. After the topping, I use pieces of 240 then 600 grade papers to further smooth the chamber walls – blending the edges of the differing layers of the Old Timer material. Smoothing the rim more also seems to harden the material more – making both the native Meerschaum lining and the Ole Timer more durable. I also give the inner rim edge a subtle rounding which protects the edge from chipping. Looking closely at where the native Meer and Ole Timer Faux Meer meet, I see a few gaps that the Ole Timer mixture did not close. These are marked with the arrows.

After the topping, I use pieces of 240 then 600 grade papers to further smooth the chamber walls – blending the edges of the differing layers of the Old Timer material. Smoothing the rim more also seems to harden the material more – making both the native Meerschaum lining and the Ole Timer more durable. I also give the inner rim edge a subtle rounding which protects the edge from chipping. Looking closely at where the native Meer and Ole Timer Faux Meer meet, I see a few gaps that the Ole Timer mixture did not close. These are marked with the arrows. One more time I bring out the chalk and egg white mixture and after mixing it, I apply more on the rim with my finger to close the gaps and then let it set for a few hours to harden.

One more time I bring out the chalk and egg white mixture and after mixing it, I apply more on the rim with my finger to close the gaps and then let it set for a few hours to harden. Again, I sand…

Again, I sand…

…and declare that the Meerschaum chamber repair is complete! I’m pleased with the what I’m seeing – as I said before, it ain’t pretty, but this pipe has a chance for another lifetime and that makes this long, methodical process worth the trouble. Altogether, I’ve been working on this Meer-lining repair about a week or so. The true test for both the stummel’s crack repair and the Meerschaum, and how well the Old Timer Faux Meer holds up, will come after the chamber is put into service. The physics of the heat – expansion and contraction – will show no favorites and we’ll see what the result will be!

…and declare that the Meerschaum chamber repair is complete! I’m pleased with the what I’m seeing – as I said before, it ain’t pretty, but this pipe has a chance for another lifetime and that makes this long, methodical process worth the trouble. Altogether, I’ve been working on this Meer-lining repair about a week or so. The true test for both the stummel’s crack repair and the Meerschaum, and how well the Old Timer Faux Meer holds up, will come after the chamber is put into service. The physics of the heat – expansion and contraction – will show no favorites and we’ll see what the result will be! Anxious to see the stem and stummel reunited, I peel away the masking tape and clean the exposed stummel with a cotton pad wetted with alcohol. Not bad!

Anxious to see the stem and stummel reunited, I peel away the masking tape and clean the exposed stummel with a cotton pad wetted with alcohol. Not bad! I look closely at the crack repair (formerly the Grand Crack Canyon) and it is solid, but I notice again that the crack line itself and the pipewood in the immediate area running along the crack has lightened a wee bit. It’s not surprising after using acetone to clean away the excess CA glue from the crack repair. The picture shows this well.

I look closely at the crack repair (formerly the Grand Crack Canyon) and it is solid, but I notice again that the crack line itself and the pipewood in the immediate area running along the crack has lightened a wee bit. It’s not surprising after using acetone to clean away the excess CA glue from the crack repair. The picture shows this well. To remedy this, I use an Italian made dye stick labeled, Noce Medio (Medium Night) that does a great job blending the area with the stummel.

To remedy this, I use an Italian made dye stick labeled, Noce Medio (Medium Night) that does a great job blending the area with the stummel. The surface looks great and I enhance this by applying a goodly portion of Before & After Restoration Balm to bring out the depth of the dark, burgundy speckled, blasted surface. After rubbing the Balm into the craggy surface with my fingers, I set the stummel aside for about 20 minutes allowing the Balm to do its thing.

The surface looks great and I enhance this by applying a goodly portion of Before & After Restoration Balm to bring out the depth of the dark, burgundy speckled, blasted surface. After rubbing the Balm into the craggy surface with my fingers, I set the stummel aside for about 20 minutes allowing the Balm to do its thing. And I like what it did! After 20 minutes I use a cotton cloth to wipe the excess Balm and then I follow by hand buffing with a microfiber cloth.

And I like what it did! After 20 minutes I use a cotton cloth to wipe the excess Balm and then I follow by hand buffing with a microfiber cloth. After reattaching the stem, I mount the Dremel with a cotton cloth buffing wheel and set the speed at 40% full power. I then apply Blue Diamond compound to the stem. I also apply the compound to the rim surface as well as the smooth surface on the underside of the shank holding the nomenclature.

After reattaching the stem, I mount the Dremel with a cotton cloth buffing wheel and set the speed at 40% full power. I then apply Blue Diamond compound to the stem. I also apply the compound to the rim surface as well as the smooth surface on the underside of the shank holding the nomenclature. After applying the compound, I mount another cotton cloth buffing wheel to the Dremel maintaining the same speed and apply a few coats of carnauba wax to the stem and as well a light application to the stummel. The craggy stummel surface will get gummed up if I apply too much wax, but a small amount spreads nicely with the Dremel action and brings out the luster of the dark hues of the pipewood. I finish the restoration by giving the pipe a rigorous hand buffing using a microfiber cloth.

After applying the compound, I mount another cotton cloth buffing wheel to the Dremel maintaining the same speed and apply a few coats of carnauba wax to the stem and as well a light application to the stummel. The craggy stummel surface will get gummed up if I apply too much wax, but a small amount spreads nicely with the Dremel action and brings out the luster of the dark hues of the pipewood. I finish the restoration by giving the pipe a rigorous hand buffing using a microfiber cloth.

This restoration was a labor of love – this gargantuan pipe wanted another opportunity to serve and I hope my repairs have given him a fighting chance! As I said earlier, the proof of this pudding will be in the heating and cooling of the stummel. The Old Timer Faux Meerschaum is a durable material after it sets up and hardens. The key will be if the Ole Timer material bonds and moves with the native Meerschaum during the heating and cooling. We’ll see! My good friend in India, Paresh, commissioned this giant Kilimanjaro to benefit the work we do here in Bulgaria with the Daughters of Bulgaria – women and girls who have been trafficked and sexually exploited. I’m going to propose to Paresh that if he would like, I can send the Kilimanjaro to him to put it into service for a few months to see how the repairs fair then settle up 😊. If not, I’ll keep the Kilimanjaro in my own collection and see how he does! Thanks for joining me! It’s not pretty! ThePipeSteward

This afternoon I decided to start working on the fourth of the pipes – a sandblast freehand. It was the one on the left top held in the hand in the photo above. It was a Freehand Shape with a plateau rim top and a smooth shank end. It had a fancy turned saddle stem that was oxidized, calcified and had lots of tooth marks and chatter on both sides near the button. The bowl had a thick cake on the walls and a heavy lava coat in the plateau on the rim top. It was internally a mess. The finish was dirty and had grime ground into the sides of the bowl. There a crack running from the heel of the bowl half way up the bowl on both sides mid bowl. The shank was in good shape with no nicks or cracks. The pipe was stamped on the underside of the shank and read Knute [over] Of Denmark. There was no other stamping on the shank sides. I took photos of the pipe when I unpacked it to examine it. I have included those below.

This afternoon I decided to start working on the fourth of the pipes – a sandblast freehand. It was the one on the left top held in the hand in the photo above. It was a Freehand Shape with a plateau rim top and a smooth shank end. It had a fancy turned saddle stem that was oxidized, calcified and had lots of tooth marks and chatter on both sides near the button. The bowl had a thick cake on the walls and a heavy lava coat in the plateau on the rim top. It was internally a mess. The finish was dirty and had grime ground into the sides of the bowl. There a crack running from the heel of the bowl half way up the bowl on both sides mid bowl. The shank was in good shape with no nicks or cracks. The pipe was stamped on the underside of the shank and read Knute [over] Of Denmark. There was no other stamping on the shank sides. I took photos of the pipe when I unpacked it to examine it. I have included those below.

I took a photo of the bowl and rim top to show the condition of both. You can see the debris in the bowl and lava in the plateau surface of the rim top. I also took photos of the heavily oxidized and calcified stem showing the tooth marks and chatter on both sides ahead of the button.

I took a photo of the bowl and rim top to show the condition of both. You can see the debris in the bowl and lava in the plateau surface of the rim top. I also took photos of the heavily oxidized and calcified stem showing the tooth marks and chatter on both sides ahead of the button. I took a photo of the stamping on the underside of the shank. It is clear and readable as noted above. I took a photo of the bowl with the stem removed to give a sense of the proportion and appearance of the pipe without the stem.

I took a photo of the stamping on the underside of the shank. It is clear and readable as noted above. I took a photo of the bowl with the stem removed to give a sense of the proportion and appearance of the pipe without the stem.

I took photos of the crack in the bowl sides before I started my clean up and repairs. It looks like the kind of crack that come from a bowl being dropped on a hard surface.

I took photos of the crack in the bowl sides before I started my clean up and repairs. It looks like the kind of crack that come from a bowl being dropped on a hard surface. Before I started my work on the pipe I wanted to remind myself of the provenance of the pipe. I remembered that it was linked to Karl Erik as I have worked on quite a few Knute Freehands. I wanted to know where this pipe fit into the Karl Erik lines so I turned to the first of two sites that I always check to gather information on a brand. I turned to the first source of information site – Pipephil’s (http://www.pipephil.eu/logos/en/logo-k3.html) got a quick overview on the brand once again connecting it to Karl Erik.

Before I started my work on the pipe I wanted to remind myself of the provenance of the pipe. I remembered that it was linked to Karl Erik as I have worked on quite a few Knute Freehands. I wanted to know where this pipe fit into the Karl Erik lines so I turned to the first of two sites that I always check to gather information on a brand. I turned to the first source of information site – Pipephil’s (http://www.pipephil.eu/logos/en/logo-k3.html) got a quick overview on the brand once again connecting it to Karl Erik.

I turned to Pipedia (https://pipedia.org/wiki/Karl_Erik). Pipedia had this great picture of Karl Erik Ottendahl and I decided to include it here as a reminder of the artisan who first carved and released this pipe. Reminded of the tie to Karl Erik, I knew a bit about the pipe at hand. I turned to address the pipe itself. There it is clearly identified and linked to Karl Erik Ottendahl. It is designated as a second and frequently having rustication. The interesting thing is that his pipe does not look like a second at all and I wonder if the Knute is a line of Karl Erik’s rather than a second. Who knows? This one is a very well done sandblast pipe. Now it was time to work on the pipe and bring it back to life. The crack needed to be repaired and the bowl brought back to life.

I turned to Pipedia (https://pipedia.org/wiki/Karl_Erik). Pipedia had this great picture of Karl Erik Ottendahl and I decided to include it here as a reminder of the artisan who first carved and released this pipe. Reminded of the tie to Karl Erik, I knew a bit about the pipe at hand. I turned to address the pipe itself. There it is clearly identified and linked to Karl Erik Ottendahl. It is designated as a second and frequently having rustication. The interesting thing is that his pipe does not look like a second at all and I wonder if the Knute is a line of Karl Erik’s rather than a second. Who knows? This one is a very well done sandblast pipe. Now it was time to work on the pipe and bring it back to life. The crack needed to be repaired and the bowl brought back to life.

I cleaned out the internals of the bowl and shank with pipe cleaners, cotton swabs, shank brushes and 99% isopropyl alcohol. It was very clean and it looked and smelled far better. I also cleaned out the internals in the stem with the same tools and alcohol.

I cleaned out the internals of the bowl and shank with pipe cleaners, cotton swabs, shank brushes and 99% isopropyl alcohol. It was very clean and it looked and smelled far better. I also cleaned out the internals in the stem with the same tools and alcohol. I scrubbed the externals of the bowl and shank with undiluted Murphy’s Oil Soap and a tooth brush. I worked over the bowl, shank and rim top with the soap and then rinsed it off warm water. The bowl looked extremely good. The cracks around the bowl heel and sides were clean. The plateau top had some darkening and burn marks.

I scrubbed the externals of the bowl and shank with undiluted Murphy’s Oil Soap and a tooth brush. I worked over the bowl, shank and rim top with the soap and then rinsed it off warm water. The bowl looked extremely good. The cracks around the bowl heel and sides were clean. The plateau top had some darkening and burn marks.

I worked over the rim top with a brass bristle wire brush to clean up the rim top. I sanded the rim top high spots in the plateau with a 320 grit sanding pad. The clean high spots would provide a great contrast.

I worked over the rim top with a brass bristle wire brush to clean up the rim top. I sanded the rim top high spots in the plateau with a 320 grit sanding pad. The clean high spots would provide a great contrast. Now it was time to address the crack in the bowl running up both sides from the heel. The inside of the bowl is clean and no cracks run through from the outside of the bowl. I am pretty confident that the cracks came when the pipe was dropped on the ground. I used a micro drill bit and drilled small pilot holes at the end of the crack on each side of the bowl. I have circled the drill holes on both sides of the pipe in red for quick reference.

Now it was time to address the crack in the bowl running up both sides from the heel. The inside of the bowl is clean and no cracks run through from the outside of the bowl. I am pretty confident that the cracks came when the pipe was dropped on the ground. I used a micro drill bit and drilled small pilot holes at the end of the crack on each side of the bowl. I have circled the drill holes on both sides of the pipe in red for quick reference.  I filled in the cracks with clear CA glue and briar dust and used a dental spatula to press the material into the crack.

I filled in the cracks with clear CA glue and briar dust and used a dental spatula to press the material into the crack. I worked over the repaired areas with a brass bristle wire brush. I followed the flow of the sandblast finish with the brush and was able to clean up the debris from the repairs in the grain of the crack.

I worked over the repaired areas with a brass bristle wire brush. I followed the flow of the sandblast finish with the brush and was able to clean up the debris from the repairs in the grain of the crack.  I worked some Before & After Restoration Balm into the sandblast finish and the plateau rim top. I worked it in with my finger tips on the smooth portions of the finish and with a shoebrush on the plateau and the sandblast. I let the Balm do its magic for 15 minutes then buffed it off with a cotton cloth. The rich colours of the finish on this Knute looked amazing.

I worked some Before & After Restoration Balm into the sandblast finish and the plateau rim top. I worked it in with my finger tips on the smooth portions of the finish and with a shoebrush on the plateau and the sandblast. I let the Balm do its magic for 15 minutes then buffed it off with a cotton cloth. The rich colours of the finish on this Knute looked amazing.

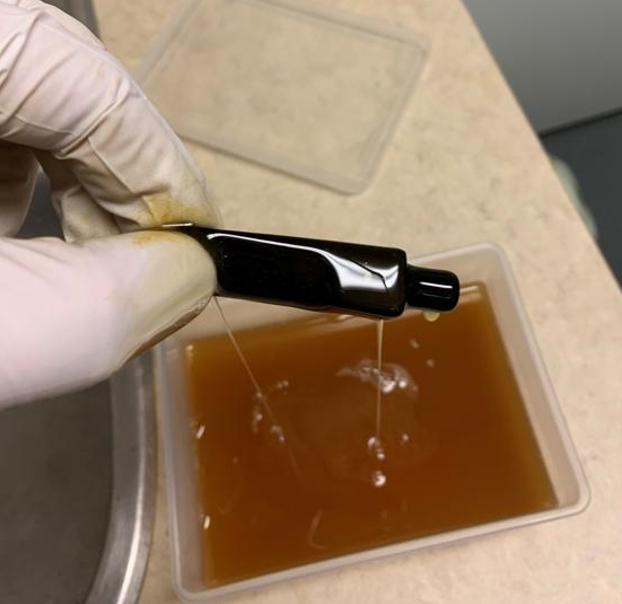

I painted the walls of the bowl with a mixture of sour cream and activated charcoal powder. The mixture works to provide a bowl coating. I applied it with a folded pipe cleaner. I put a pipe cleaner in the airway to close the entry into the bowl. The bowl coating would give the bowl some initial protection as it is broken in through smoking. The natural buildup of carbon will further protect the bowl. I set the bowl in a pipe rest to let the mixture harden and cure.

I painted the walls of the bowl with a mixture of sour cream and activated charcoal powder. The mixture works to provide a bowl coating. I applied it with a folded pipe cleaner. I put a pipe cleaner in the airway to close the entry into the bowl. The bowl coating would give the bowl some initial protection as it is broken in through smoking. The natural buildup of carbon will further protect the bowl. I set the bowl in a pipe rest to let the mixture harden and cure.

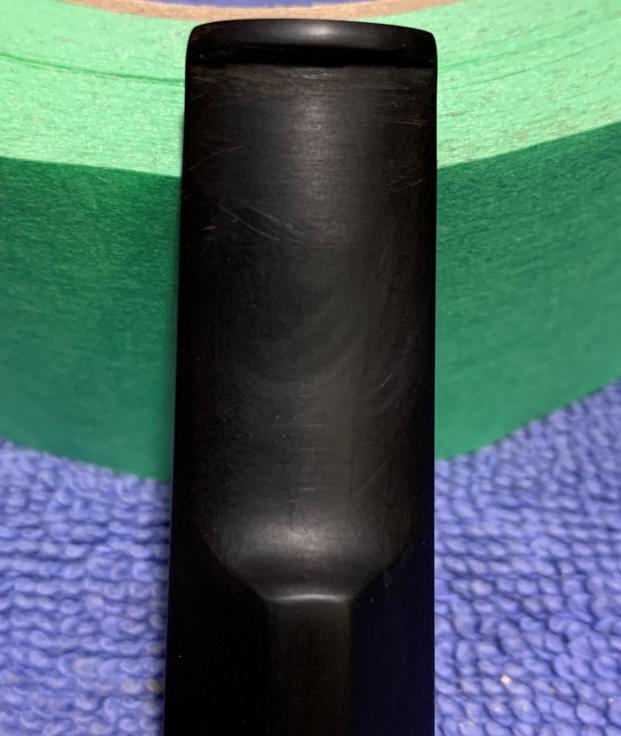

I set the bowl aside and turned my attention to the badly oxidized stem. I scrubbed the stem surface with Soft Scrub cleanser to break through the oxidization and calcification. It took a lot of scrubbing and scraping of the grime from the surface but it finally began to show black.

I set the bowl aside and turned my attention to the badly oxidized stem. I scrubbed the stem surface with Soft Scrub cleanser to break through the oxidization and calcification. It took a lot of scrubbing and scraping of the grime from the surface but it finally began to show black.  There were deep tooth marks on the top and underside of the stem ahead of the button. I filled them in with black CA glue strengthened with rubber and carbon. It dries hard but it still is a bit flexible. I flattened the repairs with small flat file.

There were deep tooth marks on the top and underside of the stem ahead of the button. I filled them in with black CA glue strengthened with rubber and carbon. It dries hard but it still is a bit flexible. I flattened the repairs with small flat file.

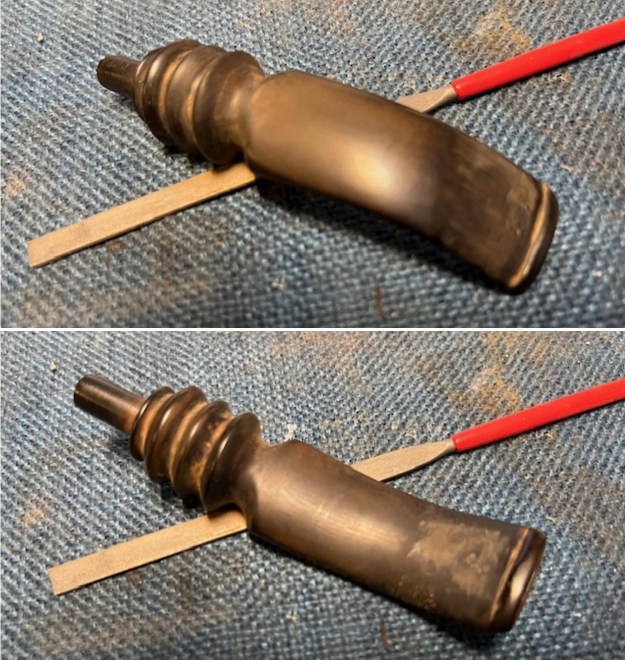

I sanded the repaired areas and the rest of stem with 320-3500 grit sanding pads to smooth it out and remove remaining oxidation. I wiped the stem down after each pad with an Obsidian Oil cloth. It was beginning to look very good.

I sanded the repaired areas and the rest of stem with 320-3500 grit sanding pads to smooth it out and remove remaining oxidation. I wiped the stem down after each pad with an Obsidian Oil cloth. It was beginning to look very good.  I polished the stem with micromesh sanding pads – 1500-12000 grit pads. I wiped it down with a damp cloth after each sanding pad. I used Before & After Pipe Polish – both Fine and Extra Fine to further polish the stem.

I polished the stem with micromesh sanding pads – 1500-12000 grit pads. I wiped it down with a damp cloth after each sanding pad. I used Before & After Pipe Polish – both Fine and Extra Fine to further polish the stem.

I put the stem back on the Knute of Denmark Sandblast Freehand pipe and took the pipe to the buffer. I carefully buffed the bowl and stem with Blue Diamond to polish the briar and the vulcanite. Blue Diamond does a great job on the smaller scratches that remain in the vulcanite. I gave the bowl multiple coats of Conservator’s Wax and the stem several coats of carnauba wax and buffed the pipe with a clean buffing pad to raise the shine. I hand buffed it with a microfiber cloth to deepen the shine. The pipe polished up really nicely with a great contrasting stain look to the briar. The finished pipe is shown in the photos below. This is a beautiful Karl Eric Made Knute of Denmark Freehand – the fancy turned stem and plateau rim top give the pipe a great look. The dimensions of the pipe are Length: 6 inches, Height: 2 ½ inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 ½ inches wide x 2 inches, Chamber diameter: 7/8 of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 2.26 ounces/64 grams. This is the fourth of six pipes that am restoring for Mario from his Dad’s collection. I look forward to hearing what he thinks of this newly restored pipe. Thanks for reading this blog and my reflections on the pipe while I worked on it!