by Steve Laug

Yesterday afternoon I was visited by a pipe man here in Vancouver named Sergey who had five Peterson’s pipes that he wanted me to work on. They are shown in the photo below. In the left column from top to bottom: Peterson’s of Dublin Kinsale XL17, Peterson’s of Dublin Filter 68, Peterson’s of Dublin Kinsale XL16 Rusticated Pipe. In the right column from top to bottom Peterson’s of Dublin Kinsale XL16 and the bottom pipe is a Peterson’s of Dublin Kinsale XL14. All five pipes were all thickly caked and had thick lava on the rim top. The cake is so thick that I could not put my little finger in the bowl it was so heavily caked. My guess was that the bottom of the bowl was lower than the entrance of the airway into the bowl. The Rusticated Kinsale XL17 also had a burn out in the front bottom of the bowl that would take a lot more time than just a simple clean up. I would know more about the condition of each of the bowls once I had reamed and cleaned them. Sergey was travelling in two weeks and he chose at least two of them that he wanted to take with him on his trip so those would be first. My hope is to try to finish four of the five. The first of these that he wanted is the one I chose to work first. It was the Peterson’s of Dublin Kinsale XL15. I took photos of the Peterson’s of Dublin Kinsale XL15 before I started working on it. The finish is very dirty with oils and dirt ground into the briar. The rim top is thickly covered with tarry lava overflowing from the heavy cake in the bowl. The cake was thick and heavy all the way to the bottom of the bowl. The vulcanite stem is also very dirty. There was oxidation, calcification and tooth marks and chatter on both sides of the stem ahead of the button and lip edge. The P stamp on the left side of the stem is a gold P that is faint and faded.

I took photos of the Peterson’s of Dublin Kinsale XL15 before I started working on it. The finish is very dirty with oils and dirt ground into the briar. The rim top is thickly covered with tarry lava overflowing from the heavy cake in the bowl. The cake was thick and heavy all the way to the bottom of the bowl. The vulcanite stem is also very dirty. There was oxidation, calcification and tooth marks and chatter on both sides of the stem ahead of the button and lip edge. The P stamp on the left side of the stem is a gold P that is faint and faded.

I took closeup photos of the rim top and bowl to give a sense of the dirty condition of the pipe and the thickness of the cake and lava on the bowl top. I also took photos of the stem to show the top and underside ahead of the button.

I took closeup photos of the rim top and bowl to give a sense of the dirty condition of the pipe and the thickness of the cake and lava on the bowl top. I also took photos of the stem to show the top and underside ahead of the button.  I took photos of the stamping on the shank sides. It was faint but readable through the grime and debris. It read as noted in the above paragraphs. I also took the stem off the shank and took a photo of the look and proportion of the pipe.

I took photos of the stamping on the shank sides. It was faint but readable through the grime and debris. It read as noted in the above paragraphs. I also took the stem off the shank and took a photo of the look and proportion of the pipe.

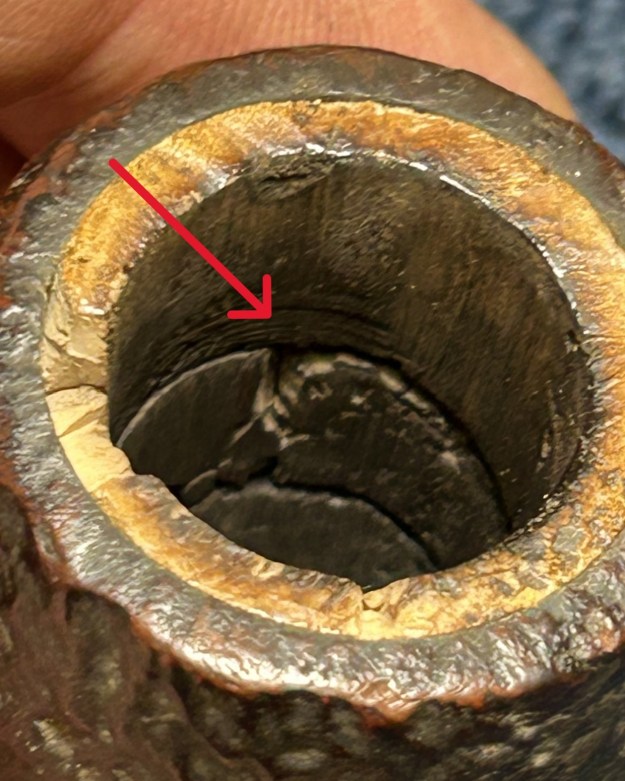

I started my work on the pipe by reaming the thick cake in the bowl. I used a PipNet pipe reamer with the first cutting head to take back the cake. I followed that with the second and the third cutting head. I was able to remove all of the cake. The cake in the bottom third of the bowl was hard. I used a Savinelli Fitsall Pipe Knife to scrape the remainder of the cake out of the bowl and clean up the bottom of the bowl. I sanded the bowl walls with 220 grit sandpaper wrapped around a piece of dowel. With the bowl cleaned out I was able to determine that the bowl bottom was almost a full ¼ inch below the airway entrance to the bowl. I would need to build up the bottom of the bowl to the entrance of the airway. It would also protect the bottom from burning out.

I started my work on the pipe by reaming the thick cake in the bowl. I used a PipNet pipe reamer with the first cutting head to take back the cake. I followed that with the second and the third cutting head. I was able to remove all of the cake. The cake in the bottom third of the bowl was hard. I used a Savinelli Fitsall Pipe Knife to scrape the remainder of the cake out of the bowl and clean up the bottom of the bowl. I sanded the bowl walls with 220 grit sandpaper wrapped around a piece of dowel. With the bowl cleaned out I was able to determine that the bowl bottom was almost a full ¼ inch below the airway entrance to the bowl. I would need to build up the bottom of the bowl to the entrance of the airway. It would also protect the bottom from burning out.

I scrubbed the externals of the bowl and shank with undiluted Murphy’s Oil Soap and a tooth brush. I rinsed it with warm running water and repeated the scrubbing and rinsing process until the pipe was clean and looked better.

I scrubbed the externals of the bowl and shank with undiluted Murphy’s Oil Soap and a tooth brush. I rinsed it with warm running water and repeated the scrubbing and rinsing process until the pipe was clean and looked better.

I scrubbed out the internals with 99% isopropyl alcohol, cotton swabs and pipe cleaners. I worked them through the airway in the shank and stem, the mortise. It took a few cleaners and swabs to really clean it but it is looking and smelling much better.

I scrubbed out the internals with 99% isopropyl alcohol, cotton swabs and pipe cleaners. I worked them through the airway in the shank and stem, the mortise. It took a few cleaners and swabs to really clean it but it is looking and smelling much better.  I sanded the bowl with 320-3500 grit sanding pads to remove some of the darkening around the bowl. I wiped it down after each sanding pad with a damp cloth to remove the sanding debris. It really began to look very good.

I sanded the bowl with 320-3500 grit sanding pads to remove some of the darkening around the bowl. I wiped it down after each sanding pad with a damp cloth to remove the sanding debris. It really began to look very good.

I polished the bowl with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding with 1500-12000 grit pads. Each pad gave it more of a shine. I wiped the bowl down after each pad with a damp cloth. By the end the bowl looked very good.

I polished the bowl with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding with 1500-12000 grit pads. Each pad gave it more of a shine. I wiped the bowl down after each pad with a damp cloth. By the end the bowl looked very good.

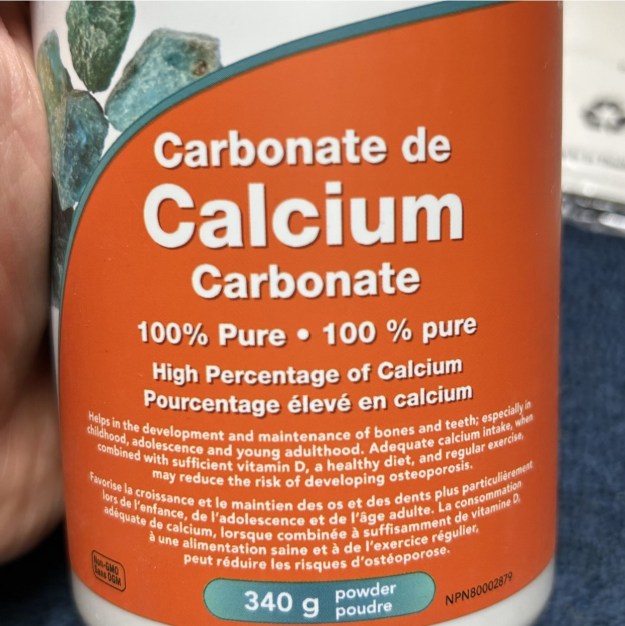

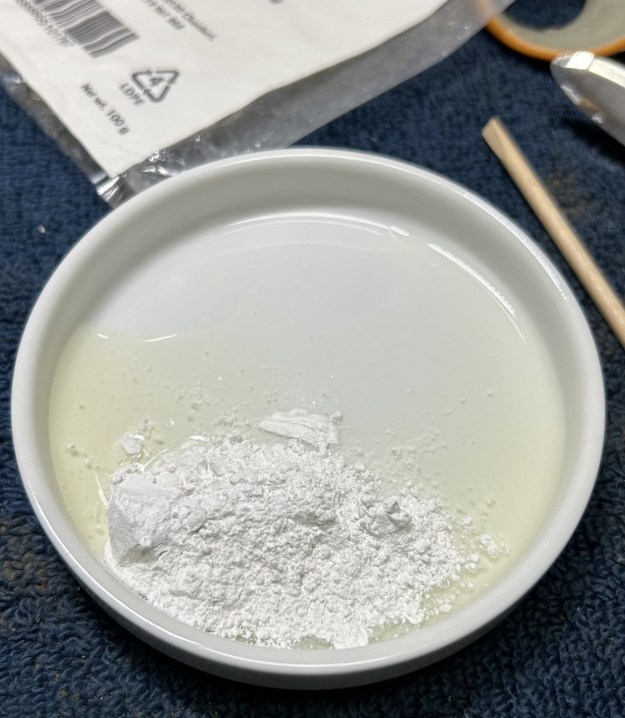

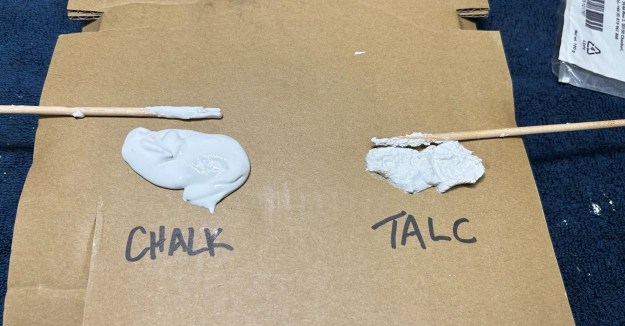

Once I had I polished the bowl I addressed overly deep bowl bottom. I filled in the bottom with a mix of cigar ash and water to make a pipe mud. I pressed it into place with a tamper to flatten it. I put a pipe cleaner in the airway so that I would only fill it to the bottom of the pipe cleaner. I set it aside to dry and harden. It looks much better. It will take awhile to harden but it should deal with the damage. If it shrinks when it cures I will need to fill it in a bit more.

Once I had I polished the bowl I addressed overly deep bowl bottom. I filled in the bottom with a mix of cigar ash and water to make a pipe mud. I pressed it into place with a tamper to flatten it. I put a pipe cleaner in the airway so that I would only fill it to the bottom of the pipe cleaner. I set it aside to dry and harden. It looks much better. It will take awhile to harden but it should deal with the damage. If it shrinks when it cures I will need to fill it in a bit more. At this point I rubbed the briar down with Before & After Restoration Balm. I worked it into the briar with my fingertips to work it into the finish. The product works to clean, enliven and preserve the briar. I let it sit for 10 minutes then I buffed it with a cotton cloth to deepen the shine. The briar really comes alive with the balm.

At this point I rubbed the briar down with Before & After Restoration Balm. I worked it into the briar with my fingertips to work it into the finish. The product works to clean, enliven and preserve the briar. I let it sit for 10 minutes then I buffed it with a cotton cloth to deepen the shine. The briar really comes alive with the balm.

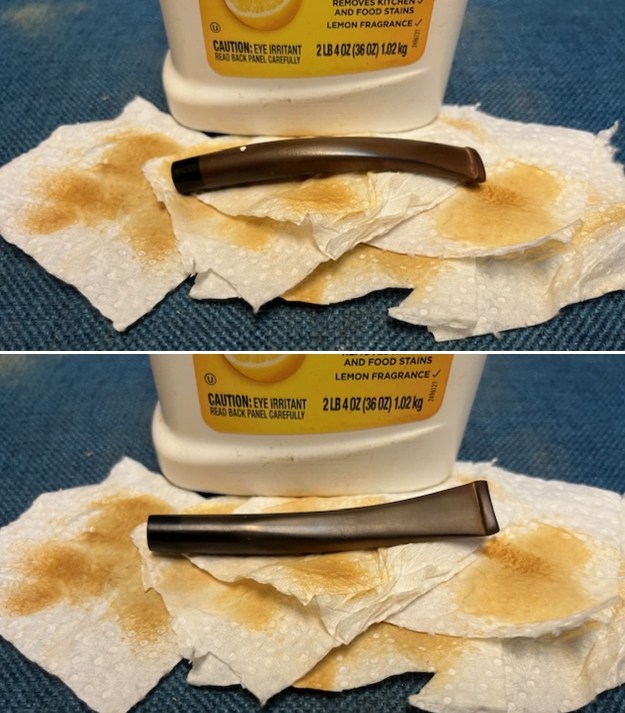

I set the bowl aside and turned my attention to the stem. I “painted” the tooth marks on both sides with the flame of a Bic lighter. I was able to lift them enough that a quick sanding with 220 grit sandpaper smoothed them out.

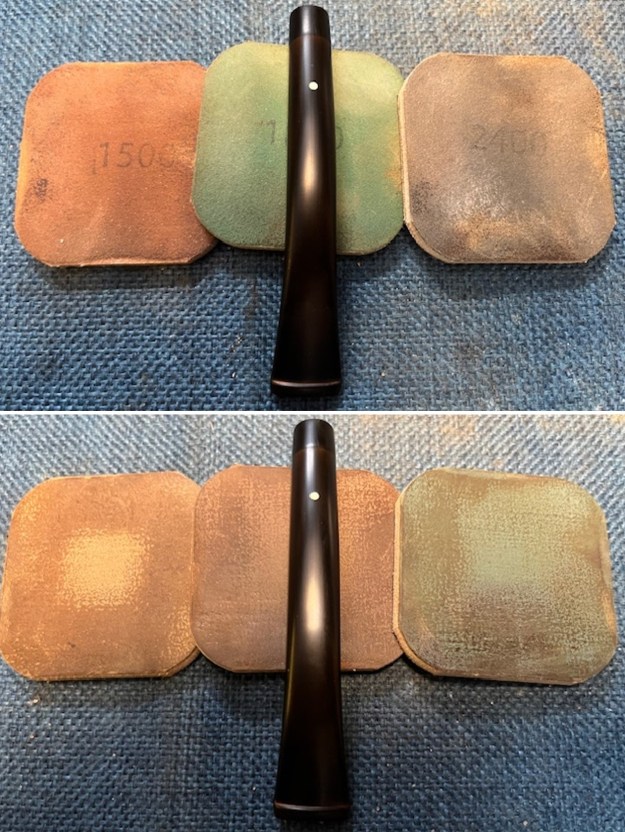

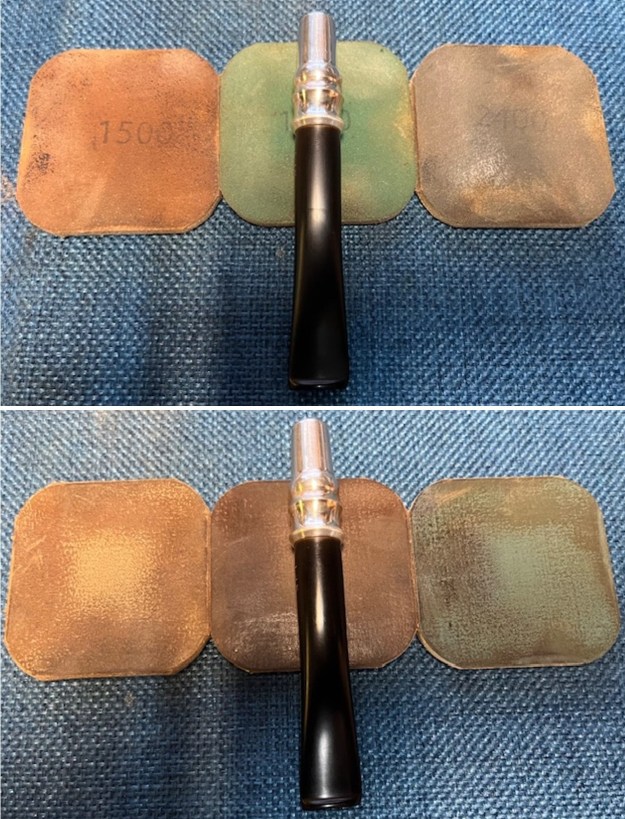

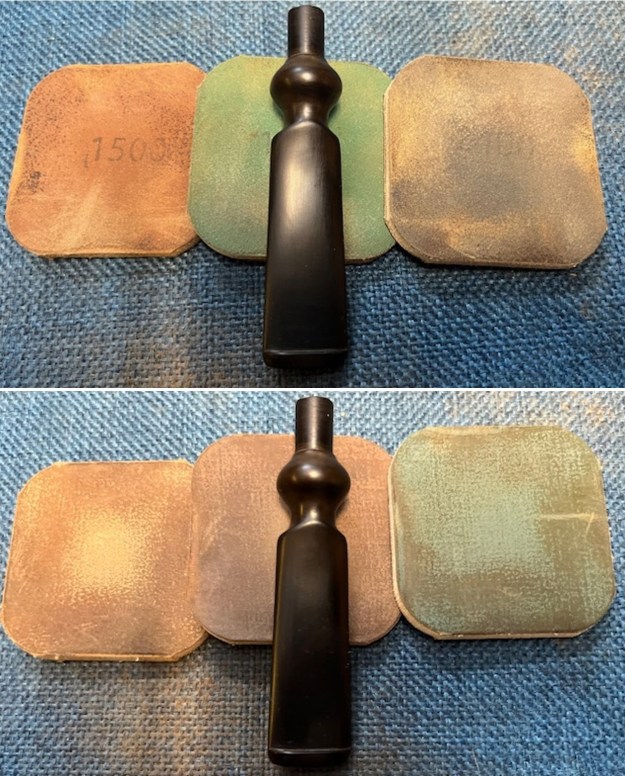

I set the bowl aside and turned my attention to the stem. I “painted” the tooth marks on both sides with the flame of a Bic lighter. I was able to lift them enough that a quick sanding with 220 grit sandpaper smoothed them out. I polished the stem with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding with 1500-12000 grit pads. Once again I wiped it down between each pad with Obsidian Oil. I further polished it with Before and After Stem Polish – both Fine and Extra Fine. It looked very good.

I polished the stem with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding with 1500-12000 grit pads. Once again I wiped it down between each pad with Obsidian Oil. I further polished it with Before and After Stem Polish – both Fine and Extra Fine. It looked very good.

This Peterson’s of Dublin Kinsale X15 Bent with a Taper Stem has a beautiful smooth finish that was slightly worn. The reddish brown finish highlights some great grain around the bowl and shank. It has a classic look of a Peterson’s pipe. The polished black vulcanite taper stem adds to the mix. I put the stem back on the bowl and buffed the pipe with Blue Diamond on the buffing wheel being careful to not buff the stamping. I gave the bowl and the stem multiple coats of carnauba wax on the buffing wheel and followed that by buffing it with a clean buffing pad. I hand buffed the pipe with a microfiber cloth to deepen the shine. The finished Peterson’s of Dublin Kinsale xL15 is quite nice and feels great in the hand. Give the finished pipe a look in the photos below. The dimensions of the pipe are Length: 6 inches, Height: 2 inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 ¼ inch, Chamber diameter: 7/8 of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 2.89 ounces/81 grams. Thanks for walking through the restoration with me as I worked over another beautiful pipe. I have four more pipes to finish before I give them back to Sergey. Thanks for your time.

This Peterson’s of Dublin Kinsale X15 Bent with a Taper Stem has a beautiful smooth finish that was slightly worn. The reddish brown finish highlights some great grain around the bowl and shank. It has a classic look of a Peterson’s pipe. The polished black vulcanite taper stem adds to the mix. I put the stem back on the bowl and buffed the pipe with Blue Diamond on the buffing wheel being careful to not buff the stamping. I gave the bowl and the stem multiple coats of carnauba wax on the buffing wheel and followed that by buffing it with a clean buffing pad. I hand buffed the pipe with a microfiber cloth to deepen the shine. The finished Peterson’s of Dublin Kinsale xL15 is quite nice and feels great in the hand. Give the finished pipe a look in the photos below. The dimensions of the pipe are Length: 6 inches, Height: 2 inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 ¼ inch, Chamber diameter: 7/8 of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 2.89 ounces/81 grams. Thanks for walking through the restoration with me as I worked over another beautiful pipe. I have four more pipes to finish before I give them back to Sergey. Thanks for your time.