by Kenneth Lieblich

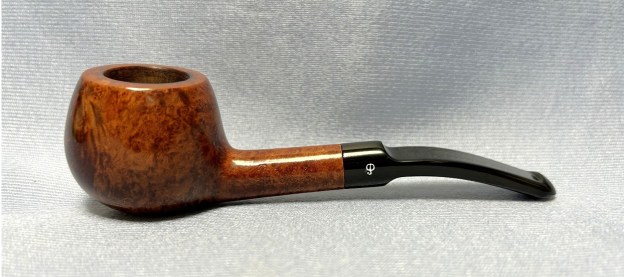

This is another in a series of pipes I cleaned up for a local family. Today, it’s a handsome Peterson Kildare 405S Prince with a P-lip saddle stem. It was a pleasure to work on this pipe, as it didn’t require too much elbow grease. In my research, I was interested to learn that this shape is apparently uncommon.

The markings are as follows: on the left shank, we read Peterson’s [over] “Kildare”; on the right shank, we read Made in the [over] Republic [over] of Ireland. Immediately to the right of that is the shape number, 405S. Finally, on the stem, we see the stylized P of the Peterson Pipe Company.

The markings are as follows: on the left shank, we read Peterson’s [over] “Kildare”; on the right shank, we read Made in the [over] Republic [over] of Ireland. Immediately to the right of that is the shape number, 405S. Finally, on the stem, we see the stylized P of the Peterson Pipe Company. In looking up this pipe shape, I came upon a page from Mark Irwin’s blog, Peterson Pipe Notes. It had some useful information on the 400 series in general and this very pipe in particular:

In looking up this pipe shape, I came upon a page from Mark Irwin’s blog, Peterson Pipe Notes. It had some useful information on the 400 series in general and this very pipe in particular:

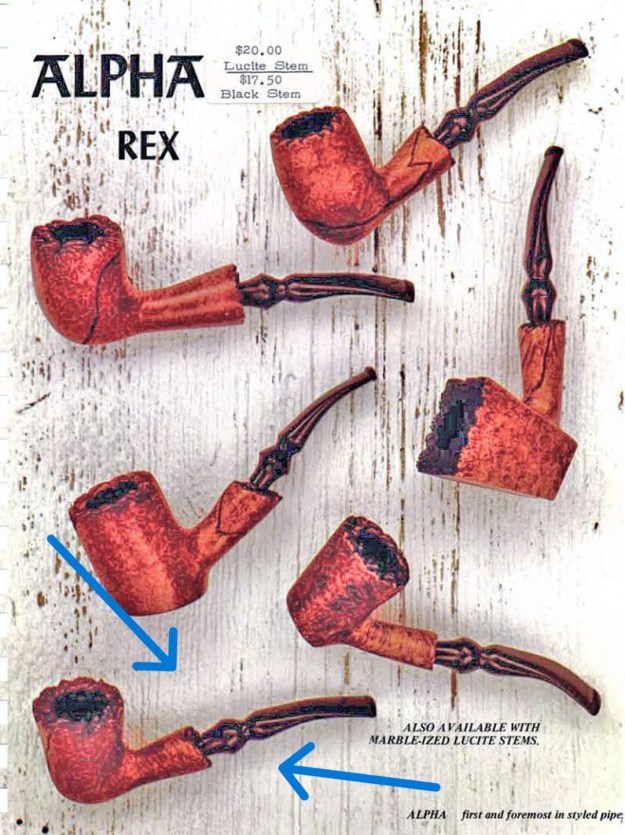

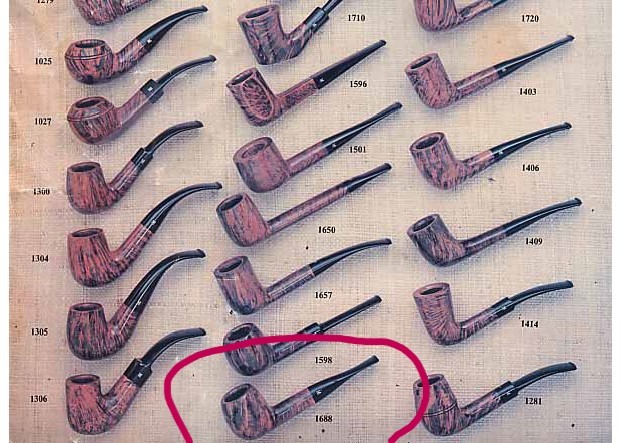

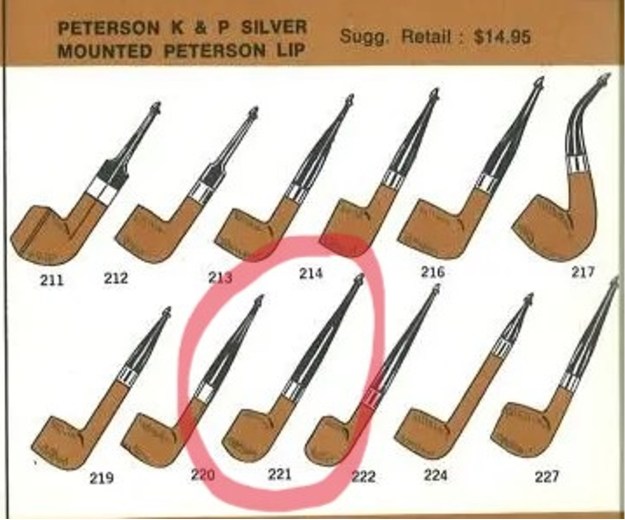

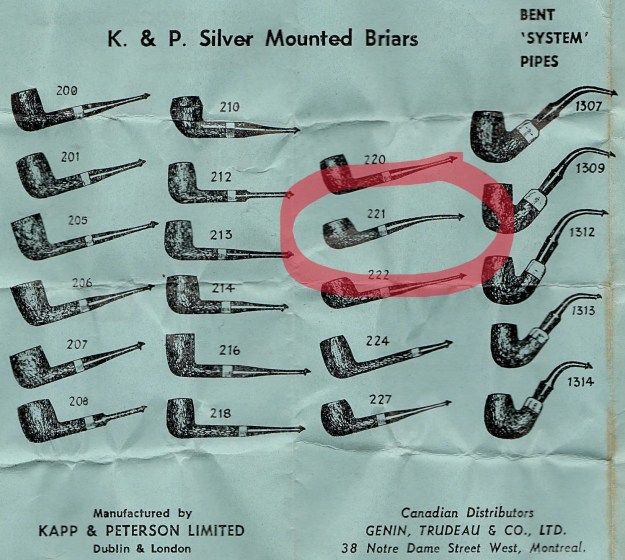

The 400-shape group has come to the forefront with Peterson’s recent reboot of the 406 “Large Prince”. It’s an interesting and usually overlooked group, comprised of straight shapes influenced by the classic English chart. Insofar as the catalogs are concerned (which are never, of course, identical with actual production dates), the shape group begins quite understandably shortly after Peterson opened its London factory in the Bradley Buildings in 1937—England at the time being one of Peterson’s “Big Three” markets (the other two being the US and Germany). As a group, the shapes reflect the smoking styles of the mid-twentieth century—the 1940s, 50s and 60s—the decades that produced most of them. That is, they are smaller pipes than most pipemen (and women) use today and they’re lighter, designed for the comfort of constant clenching in an office or factory environment where both hands were needed, and for the shorter, probably more frequent smokes that the interruptions of the workday entails. While I’ve been able to document 21 shapes, probably no more than 8 to 10 were ever offered at one time, and for most decades considerably less. Once in a while Peterson, being the counter-cultural wags they are, will subvert the English aesthetic by giving a shape a “bit of the Irish,” adding what they call an “S/B” or “Semi-Bent” mouthpiece—a piece of Peterson lore that even Peterson has forgotten!

The 405s was first announced in the 1979 update to the 1975 catalog and released in the various Classic Range lines, documented in the Kildare, Kildare Patch and Sterling. It was extremely short-lived, however, and is not found in any subsequent Peterson catalogs. Whether it was slightly larger or smaller than the 406 and 407 is hard to say, especially when the 406 and 407 almost seem to be interchangeable.

I also understand that the 405S most closely resembles the modern-day 408. The two are not identical, but pretty close. Let’s look at the condition of the pipe. As mentioned, the condition is really quite good. There’s a bit of wear and tear on the rim of the bowl, but nothing serious – and it looks like the inside of the bowl was cleaned out at some point. The stem also has a few tooth marks, but no significant calcification and only a bit of oxidation. To begin, I used oil soap on a few cotton rounds and wiped the stem down to provide an initial cleaning of filth before moving on to the next steps. The primary cleaning comes next. I cleaned the inside of the stem with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in 99% lemon-infused isopropyl alcohol. I scrubbed thoroughly to make sure the interior was clean.

To begin, I used oil soap on a few cotton rounds and wiped the stem down to provide an initial cleaning of filth before moving on to the next steps. The primary cleaning comes next. I cleaned the inside of the stem with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in 99% lemon-infused isopropyl alcohol. I scrubbed thoroughly to make sure the interior was clean. The goal of the next step is the removal (or minimization) of oxidation. Going to my sink, I used cream cleanser, cotton rounds, and a toothbrush, and scoured the stem to remove as much surface oxidation as possible. As the photos show, the result is a hideous brownish mess – but better off the stem than on it.

The goal of the next step is the removal (or minimization) of oxidation. Going to my sink, I used cream cleanser, cotton rounds, and a toothbrush, and scoured the stem to remove as much surface oxidation as possible. As the photos show, the result is a hideous brownish mess – but better off the stem than on it. Once the stem was reasonably clean, I soaked it overnight in some de-oxidation fluid. This solution works to draw oxidation in the stem to the surface. This is a major aid and an important step in ensuring a clean stem. The following day, I drew the stem out from its bath and scrubbed the lingering fluid with a toothbrush.

Once the stem was reasonably clean, I soaked it overnight in some de-oxidation fluid. This solution works to draw oxidation in the stem to the surface. This is a major aid and an important step in ensuring a clean stem. The following day, I drew the stem out from its bath and scrubbed the lingering fluid with a toothbrush. Now that the stem is clean and dry, I set about fixing the very minor dents in the vulcanite. This is done by filling those divots with black cyanoacrylate adhesive, impregnated with carbon and rubber. I left this to cure and moved on.

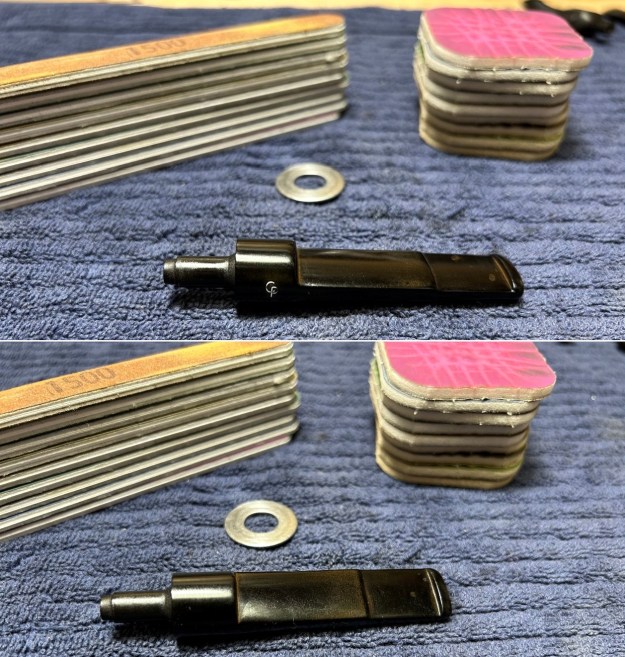

Now that the stem is clean and dry, I set about fixing the very minor dents in the vulcanite. This is done by filling those divots with black cyanoacrylate adhesive, impregnated with carbon and rubber. I left this to cure and moved on. After this, I painted the logo on the stem with some nail polish. I restored the logo carefully and let it fully set before proceeding.

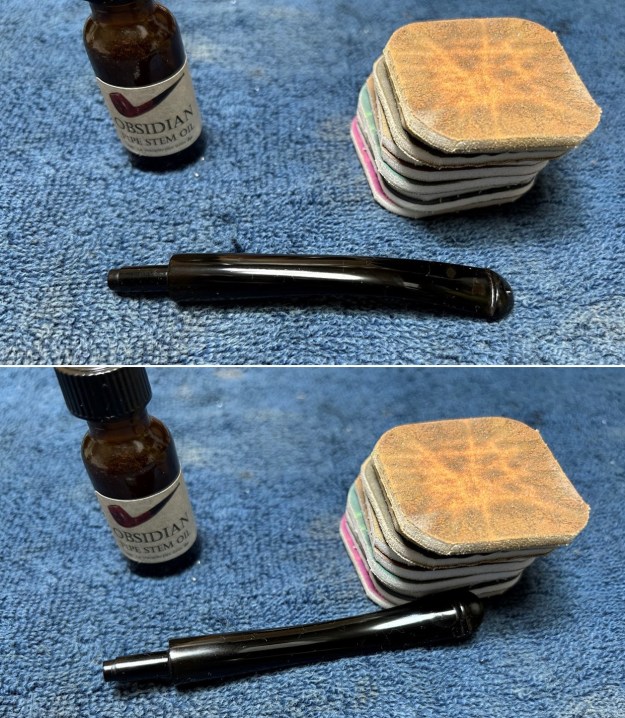

After this, I painted the logo on the stem with some nail polish. I restored the logo carefully and let it fully set before proceeding. The penultimate step for the stem is sanding. First, with my set of needle files, I reduce the bulk of the cyanoacrylate repairs. I want to remove the excess adhesive as near to the surface as possible, without cutting into the vulcanite. Following that, I use all nine of the micromesh sanding pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand out flaws, even out the vulcanite, and provide gentle polishing of the finished surface. I also apply pipe-stem oil while using the last five micromesh pads. There was a wonderful, deep black shine to the stem when I was done.

The penultimate step for the stem is sanding. First, with my set of needle files, I reduce the bulk of the cyanoacrylate repairs. I want to remove the excess adhesive as near to the surface as possible, without cutting into the vulcanite. Following that, I use all nine of the micromesh sanding pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand out flaws, even out the vulcanite, and provide gentle polishing of the finished surface. I also apply pipe-stem oil while using the last five micromesh pads. There was a wonderful, deep black shine to the stem when I was done. Now that the stem is (nearly) complete, I can move on to the stummel. The first step for me is to ream out the bowl – that is to say, remove all the cake inside the bowl. This accomplishes a couple of things. First (and most obviously), it cleans the bowl and provides a refurbished chamber for future smoking. Second, when the old cake is removed, I can inspect the interior walls of the bowl and determine if there is damage or not. In this case, the bowl was clean enough that I only used a a piece of sandpaper taped to a wooden dowel to remove the little debris.

Now that the stem is (nearly) complete, I can move on to the stummel. The first step for me is to ream out the bowl – that is to say, remove all the cake inside the bowl. This accomplishes a couple of things. First (and most obviously), it cleans the bowl and provides a refurbished chamber for future smoking. Second, when the old cake is removed, I can inspect the interior walls of the bowl and determine if there is damage or not. In this case, the bowl was clean enough that I only used a a piece of sandpaper taped to a wooden dowel to remove the little debris. Similar to the stem, I then cleaned the stummel with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in 99% lemon-infused isopropyl alcohol.

Similar to the stem, I then cleaned the stummel with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in 99% lemon-infused isopropyl alcohol. I then decided to ‘de-ghost’ the pipe – that is to say, exorcize the remaining filth from the briar. I filled the bowl and the shank with cotton balls, then saturated them with 99% isopropyl alcohol. I let the stummel sit overnight. This caused any remaining oils, tars and smells to leach out into the cotton.

I then decided to ‘de-ghost’ the pipe – that is to say, exorcize the remaining filth from the briar. I filled the bowl and the shank with cotton balls, then saturated them with 99% isopropyl alcohol. I let the stummel sit overnight. This caused any remaining oils, tars and smells to leach out into the cotton. To tidy up the briar, I also wiped down the outside with some oil soap on cotton rounds (and a toothbrush). This does a good job of cleaning any latent dirt on the surface of the briar. The last step of the cleaning process is to scour the inside of the stummel with some soap and tube brushes. This is the culmination of the work of getting the pipe clean.

To tidy up the briar, I also wiped down the outside with some oil soap on cotton rounds (and a toothbrush). This does a good job of cleaning any latent dirt on the surface of the briar. The last step of the cleaning process is to scour the inside of the stummel with some soap and tube brushes. This is the culmination of the work of getting the pipe clean. I then used all nine micromesh pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) on the outside of the stummel to finish it off. This sanding minimizes flaws in the briar and provides a beautiful smoothness to the wood. I rubbed some Before & After Restoration Balm into the briar and let it sit for 20 minutes or so. The balm moisturizes the wood and gives a beautiful depth to the briar. I then buffed it with a microfibre cloth.

I then used all nine micromesh pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) on the outside of the stummel to finish it off. This sanding minimizes flaws in the briar and provides a beautiful smoothness to the wood. I rubbed some Before & After Restoration Balm into the briar and let it sit for 20 minutes or so. The balm moisturizes the wood and gives a beautiful depth to the briar. I then buffed it with a microfibre cloth.

For the final step, I took the pipe to my bench buffer and carefully polished it – first with a white diamond compound, then with three coats of carnauba wax. This procedure makes the pipe look its best – the stummel sings and the stem glows.

For the final step, I took the pipe to my bench buffer and carefully polished it – first with a white diamond compound, then with three coats of carnauba wax. This procedure makes the pipe look its best – the stummel sings and the stem glows. All done! This Peterson Kildare 405S looks fantastic again and is ready to be enjoyed by its new owner. The approximate dimensions of the pipe are as follows: length 5½ in. (139 mm); height 1½ in. (37 mm); bowl diameter 1⅝ in. (40 mm); chamber diameter ¾ in. (19 mm). The weight of the pipe is 1¼ oz. (36 g). I hope you enjoyed reading the story of this pipe’s restoration as much as I enjoyed restoring it. If you are interested in more of my work, please follow me here on Steve’s website or send me an email at kenneth@knightsofthepipe.com. Thank you very much for reading and, as always, I welcome and encourage your comments.

All done! This Peterson Kildare 405S looks fantastic again and is ready to be enjoyed by its new owner. The approximate dimensions of the pipe are as follows: length 5½ in. (139 mm); height 1½ in. (37 mm); bowl diameter 1⅝ in. (40 mm); chamber diameter ¾ in. (19 mm). The weight of the pipe is 1¼ oz. (36 g). I hope you enjoyed reading the story of this pipe’s restoration as much as I enjoyed restoring it. If you are interested in more of my work, please follow me here on Steve’s website or send me an email at kenneth@knightsofthepipe.com. Thank you very much for reading and, as always, I welcome and encourage your comments.