Blog by Dal Stanton

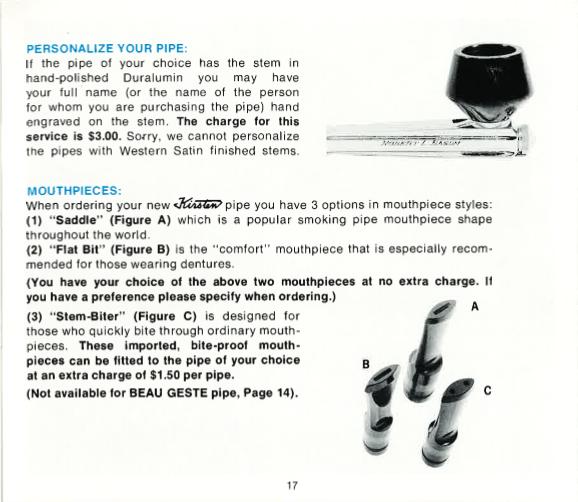

When I first saw the Meer before me on the eBay auction block, I was first attracted by the patina showing on the combination smooth and sculpted surfaces. The base of the billiard bowl showcases two opposing sculpted frescoes, one with the vineyard in expectation of fruit, and the other with the fulfillment – a rack of grapes appearing from behind the grapevine leaves. Hope and fulfillment are always pleasing themes for reflection as one smokes a bowl of his (or her!) favorite blend. The patina of the aging meerschaum is concentrated at the base of the stummel, encompassing the frescoes and then gradually thinning and lightening toward the rim and toward the shank. The other characteristic that drew my attention was the color and taper of the Bakelite stem completing the bent billiard flow. It just looked good to me. I have no idea of a carver as there are no markings on the Meer, and the only information from the seller was that its origins were in Europe – it was a gift to the original owner by his sister who lived in Belgium in the 1970s. Taking it from the ‘Help Me!’ basket, I place it on my work table here in Sofia, Bulgaria, and record the Meer’s condition when it came to me.

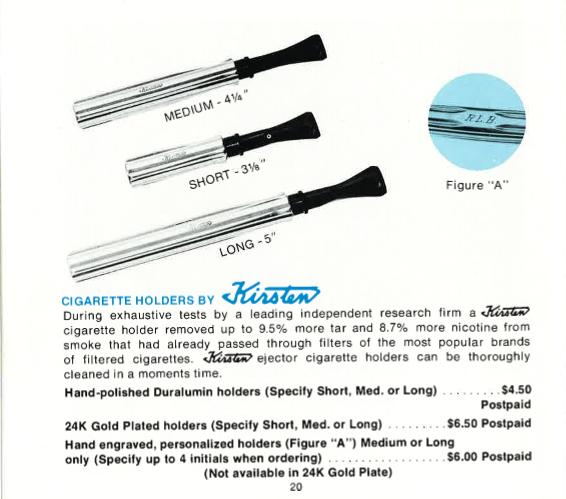

The characteristics and make-up of meerschaum are not widely understood – I know because I was among those who looked at the white coral-like material and wondered what exactly it was! The word ‘meerschaum’ has German origins, literally meaning ‘sea foam’. This brief description from Meerschaum.com is helpful:

The characteristics and make-up of meerschaum are not widely understood – I know because I was among those who looked at the white coral-like material and wondered what exactly it was! The word ‘meerschaum’ has German origins, literally meaning ‘sea foam’. This brief description from Meerschaum.com is helpful:

Meerschaum is a very rare mineral, a kind of hard white clay. Light and porous structure of the pipe keeps the smoke cool and soft. The pipe itself is a natural filter which absorbs the nicotine. Because of this peculiarity, meerschaum pipes slowly change their colors to different tones of gold and dark brown. This adds an esthetic enjoyment to its great smoking pleasure. The longer a pipe is smoked the more valuable it becomes due to the color change. Today many old and rare meerschaums have found a permanent place in museums and private collections.

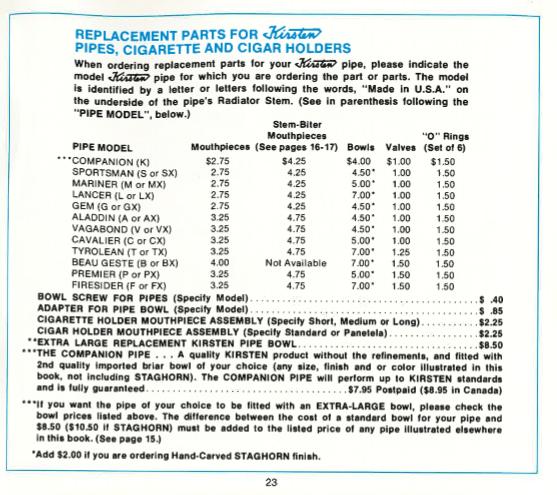

Meers are popular because they require no breaking in, no cake, and no resting between smokes. Many consider Meers to be a cooler and dryer smoking experience. The one main issue with Meers is that they don’t like to be dropped on hard floors – that is never a good thing! Most Meerschaum is mined in Turkey and for the curious who want to know what exactly the material is, one last excerpt from Altinok Meerschaum’s facts page:

The geologist knows the light, porous Meerschaum as hydrous magnesium silicate. The pipe smoker knows it as the perfect material for providing a cool, dry, flavorful smoke. The mineral itself is the fossilized shells of tiny sea creatures that fell to the ocean floor over 50 million years ago, there to be covered and compressed over the ages by layer upon layer of silt. Profound movements in the earth’s crust raised the creamy white stone of Meerschaum above sea level. There men eventually discovered it and created an incomparable pipe from it. The first record of Meerschaum as a pipe dates from around 1723.

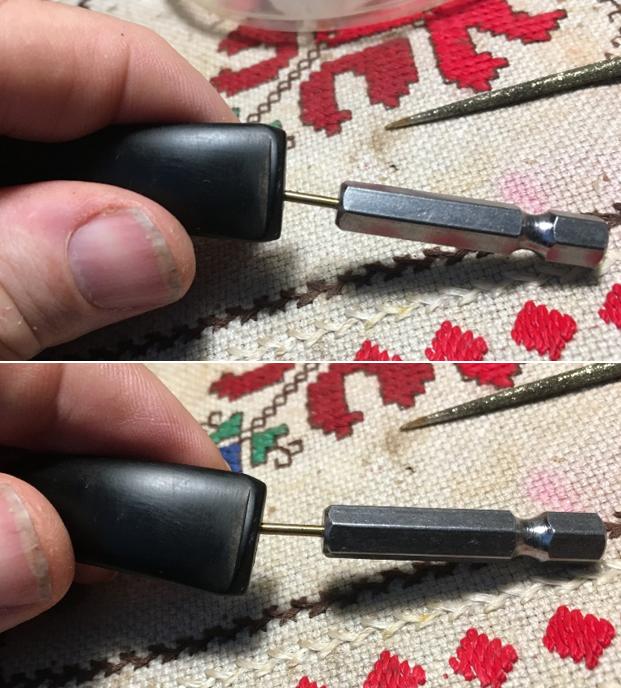

The stummel on the Meer before me has a lot of grime and dirt with nicks showing his age and that he has been well used. The challenge with Meer is always how to clean and restore but not to remove the patina, which for a Meerschaum, is the honorific equivalent of the respect owed to those blessed with gray hair and long life in the Bible. The rim has thick lava and the bowl has moderate cake which will need to be removed with care – cake is not needed on a Meer! The more daunting questions focus on the stem. The obvious challenge is the large chip on the end of the stem which also has removed almost half of the button. I could prepare for this repair by ordering and having someone bring from the US to Bulgaria Behlen’s Medium Yellow Furniture Powders to form a putty patch. I will attempt to repair the stem with the help of others – we’ll see! The other challenge that I was not able to discern from the eBay pictures, was the push tenon. The mortise was threaded for a screw in tenon but the tenon I see connected to the stem has no threads and only engages the mortise as the mortise narrows after the threads. You can see how much of the tenon is engaged by the coloration (last picture above) – only about half. When I test the engaged tenon, there is a bit of a wiggle to the stem and it isn’t solidly seated as one would expect. While the stem, when connected to the shank is usable, it isn’t ideal. I’ll give some thought to this challenge and perhaps seek counsel.

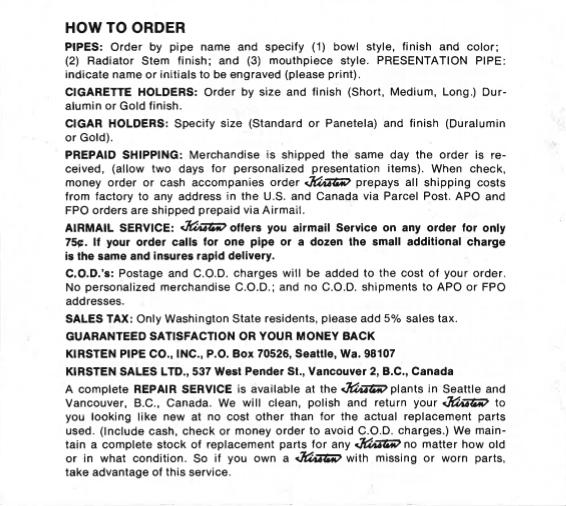

Leaving the question about the approach for the tenon, I decide to start on the clean-up of the stummel. I first clean the rim by using cotton pads wetted with isopropyl 95% – I just want to see how much of the lava and stain will come off. Not much did. I then decide to use a medium grade sanding sponge and lightly top the rim – not aiming to take off the meerschaum but to break through the crusty stuff and remove the burnt areas. That did the trick. Pictures show the progress.

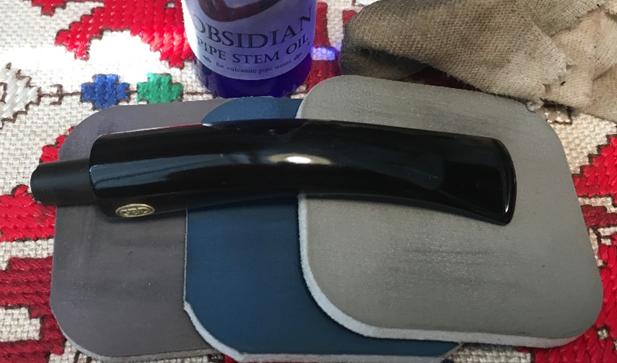

I can now see the inner edge of the chamber wall and using both a pin knife and the Savinelli Pipe Knife carefully I ream the bowl and remove the cake. I follow this by using 240 grit paper and sand the walls to remove more of the carbon. I wasn’t satisfied with the 240 grit so I rolled up some coarser 120 grit wrapped around a Sharpie Pen and that did the trick. Much nicer. I complete the reaming with cleaning the bowl with a cotton wipe wetted with isopropyl 95%. The fire chamber looks good. To remove the blackening on the inner ring of the rim, I give it a very gentle bevel with 240 grit sanding paper rolled. The pictures show the progress.

I can now see the inner edge of the chamber wall and using both a pin knife and the Savinelli Pipe Knife carefully I ream the bowl and remove the cake. I follow this by using 240 grit paper and sand the walls to remove more of the carbon. I wasn’t satisfied with the 240 grit so I rolled up some coarser 120 grit wrapped around a Sharpie Pen and that did the trick. Much nicer. I complete the reaming with cleaning the bowl with a cotton wipe wetted with isopropyl 95%. The fire chamber looks good. To remove the blackening on the inner ring of the rim, I give it a very gentle bevel with 240 grit sanding paper rolled. The pictures show the progress.

With the bowl reamed I clean the mortise internals. Using pipe cleaners and Q-tips, dipped in isopropyl 95%, I discover quickly that I’m not able to get a pipe cleaner through the mortise through the draught hole. I twist, turn and angle – it feels like there’s an obstruction. I blow through the mortise and find that air is moving through without pressure build up. Finally, the pipe cleaner moved through. Looking more closely in the mortise with a directed light I see in the throat of the mortise just beyond the end of the threading appears to be a plastic tubing. I manage to take a picture of it. I’m not sure if this is part of the internal system or something broken off and lodged. Yet, this plastic tube is what the tenon is engaging. With great difficulty, I can probe the area what appears to be beyond the tubing and find the airway which seems to be a sharp turn up from the angle of the mortise’s drilling as the pipe cleaner emerges from the plastic tubing. This doesn’t seem right. I’ll research more to see what the tubing is. The mortise is clean, so I move to the cleaning the externals of the bowl.

With the bowl reamed I clean the mortise internals. Using pipe cleaners and Q-tips, dipped in isopropyl 95%, I discover quickly that I’m not able to get a pipe cleaner through the mortise through the draught hole. I twist, turn and angle – it feels like there’s an obstruction. I blow through the mortise and find that air is moving through without pressure build up. Finally, the pipe cleaner moved through. Looking more closely in the mortise with a directed light I see in the throat of the mortise just beyond the end of the threading appears to be a plastic tubing. I manage to take a picture of it. I’m not sure if this is part of the internal system or something broken off and lodged. Yet, this plastic tube is what the tenon is engaging. With great difficulty, I can probe the area what appears to be beyond the tubing and find the airway which seems to be a sharp turn up from the angle of the mortise’s drilling as the pipe cleaner emerges from the plastic tubing. This doesn’t seem right. I’ll research more to see what the tubing is. The mortise is clean, so I move to the cleaning the externals of the bowl. To clean the external surface of the stummel, I use undiluted Murphy’s Oil Soap with a cotton pad as well as scrubbing the sculpted lines of the vineyard frescoes. The amount of grime on the surface becomes apparent as from the before and after pictures. The pictures show the progress.

To clean the external surface of the stummel, I use undiluted Murphy’s Oil Soap with a cotton pad as well as scrubbing the sculpted lines of the vineyard frescoes. The amount of grime on the surface becomes apparent as from the before and after pictures. The pictures show the progress.

I then sanded the bowl with micromesh pads not to remove every scratch, which is a sign of character and age, but to restore the shine of a vital meerschaum surface. I wet sanded the surface using pads 1500 to 2400 then dry sanded using micromesh pads 3200 to 4000. I was not aggressive but careful not to damage the patina. I like the result.

I then sanded the bowl with micromesh pads not to remove every scratch, which is a sign of character and age, but to restore the shine of a vital meerschaum surface. I wet sanded the surface using pads 1500 to 2400 then dry sanded using micromesh pads 3200 to 4000. I was not aggressive but careful not to damage the patina. I like the result. Regarding the stem and tenon questions I referenced above, I sent a note off to Steve and about the push-pull tenon system and what to do with this Meer. In the end, I decide to order a new replacement system. I sent a note and measurements off to Tim at http://www.jhlowe.com/ and am waiting for his recommendations. Since I live in Bulgaria, ordering parts from the States is no small thing as I have it sent to someone coming and they carry it for me. Saves a bit on postage.

Regarding the stem and tenon questions I referenced above, I sent a note off to Steve and about the push-pull tenon system and what to do with this Meer. In the end, I decide to order a new replacement system. I sent a note and measurements off to Tim at http://www.jhlowe.com/ and am waiting for his recommendations. Since I live in Bulgaria, ordering parts from the States is no small thing as I have it sent to someone coming and they carry it for me. Saves a bit on postage.  With the tenon situation on hold and on order, I turn to the technical part of this restoration that I’ve been anticipating for some time. Repairing the Bakelite stem or per Steve, possibly a similar material called Amberoid, has been a subject of my research. The stems most often associated with Meerschaums are the attractive, rich honey yellow color. The challenge in a repair is matching the yellow color and glass-like texture of the Bakelite or Amberoid. When I researched this question, I came across Reborn Pipes contributor, Joyal Taylor’s (aka holymolar) 3-part series on patching amber colored stems in 2014. Starting at the first essay, Stem Patch Using Amber Super Glue, Part 1, I benefited from Joyal demonstrating not only what did work well, but what didn’t. Also of benefit were the comments many others contributed at the end of the blogs. So, thanks to Joyal’s trial and error approach, I’m able to jump to a solution in Essay 3 that worked best for him. I hope I can emulate his success! Before beginning on the repair, I want the stem internals to be clean. Taking pipe cleaners dipped in isopropyl, I go to work on the stem. The resistance was a bit more than I expected. The cavity behind the screw-in tenon was gummed up good and I expended several Q-tips and a sharp and spade dental tools helped scrape the cavity walls to break up the gunk. There is some dark staining on the internal airway but the pipe cleaners are now coming out clean.

With the tenon situation on hold and on order, I turn to the technical part of this restoration that I’ve been anticipating for some time. Repairing the Bakelite stem or per Steve, possibly a similar material called Amberoid, has been a subject of my research. The stems most often associated with Meerschaums are the attractive, rich honey yellow color. The challenge in a repair is matching the yellow color and glass-like texture of the Bakelite or Amberoid. When I researched this question, I came across Reborn Pipes contributor, Joyal Taylor’s (aka holymolar) 3-part series on patching amber colored stems in 2014. Starting at the first essay, Stem Patch Using Amber Super Glue, Part 1, I benefited from Joyal demonstrating not only what did work well, but what didn’t. Also of benefit were the comments many others contributed at the end of the blogs. So, thanks to Joyal’s trial and error approach, I’m able to jump to a solution in Essay 3 that worked best for him. I hope I can emulate his success! Before beginning on the repair, I want the stem internals to be clean. Taking pipe cleaners dipped in isopropyl, I go to work on the stem. The resistance was a bit more than I expected. The cavity behind the screw-in tenon was gummed up good and I expended several Q-tips and a sharp and spade dental tools helped scrape the cavity walls to break up the gunk. There is some dark staining on the internal airway but the pipe cleaners are now coming out clean. In essay 3, Joyal employed the use of Medium Yellow Behlen Furniture Powder (pictured below) which I found on eBay at this LINK. Previously, he had employed amber colored superglue which came out too clear – lacking the opaque quality needed for a good match. In the second essay, he tried to employ a mixture of Fiebing’s yellow and orange leather dyes and thick superglue. He found that the chemistry of the dyes caused the superglue to setup instantly. Also in essay 2 he mixed StewMac 2-part clear epoxy with Fiebing’s yellow and orange dyes, which mixed well, but the results were less than satisfactory – for both the hue and the texture. The final essay he tried the powder approach using Behlen Medium Yellow with extra thick superglue and the results were the best. Below I picture the match-up between the colors of the powder and the stem. Not bad. Joyal’s final assessment was helpful for the stem I’m looking at now:

In essay 3, Joyal employed the use of Medium Yellow Behlen Furniture Powder (pictured below) which I found on eBay at this LINK. Previously, he had employed amber colored superglue which came out too clear – lacking the opaque quality needed for a good match. In the second essay, he tried to employ a mixture of Fiebing’s yellow and orange leather dyes and thick superglue. He found that the chemistry of the dyes caused the superglue to setup instantly. Also in essay 2 he mixed StewMac 2-part clear epoxy with Fiebing’s yellow and orange dyes, which mixed well, but the results were less than satisfactory – for both the hue and the texture. The final essay he tried the powder approach using Behlen Medium Yellow with extra thick superglue and the results were the best. Below I picture the match-up between the colors of the powder and the stem. Not bad. Joyal’s final assessment was helpful for the stem I’m looking at now:

This time I tried Behlen’s yellow powder w/ StewMac’s thick clear superglue. This is the best so far. Good color and opaque. Some of the powder didn’t mix in but it all polished smoothly. I had to leave the patch thick at the edge because every time I tried to sand it – smooth it [next] to the acrylic, I would remove more of the original color from the acrylic and have to add more patch material. Oh well, this may be as good as I can do, for now.

The last observation is helpful because it lets me know that the basic solidity of the patch could be ‘softer’ relatively speaking, than the stem material so that he was removing more collateral stem material than he wanted. So, off we go! I begin the patch on the Meer’s Bakelite stem by taking another close-up focusing on the patch areas. The patch has two parts. First, the side of the stem chipped off parallel with the right-side stem edge until it enters the button area. At this point the break encompasses the entire corner – stem and button. It appears to me the break was caused by dropping the Meer on a hard surface and the impact point was the end of the stem. The second part of the patch is to rebuild the button. To do this, I’ll apply a ‘surplus’ amount of the patch putty not only to the damaged, missing part, but over the entire button. This will allow me to shape a new button with adequate edges. To mix with the Behlen powder I have a newly acquired bottle of BSI Extra Thick Maxi-Cure CA glue. I’ll start the mixture aiming at a 50/50 ratio and eyeball things. I want to mix it well so that the powder is fully dissolved. I’m also not sure how much time I have before the new CA glue starts setting.

I first take 240 grit sanding paper and rough up the entire patch area to increase the bonding potential between the Bakelite and patch putty. Now, I construct a ‘slot mold’ for the button. The slot area is shaped like a concave canoe that the button edges encompass. I need to keep putty out of this area and form a mold of sorts for the putty. The results of this mold would remind one of the Wolverine in X-Men. As menacing as it appears, the center toothpick anchors the mold in the airhole and the ‘wing-picks’ are wedging the edges. The folded index card forming the mold I cover with smooth tape so it won’t adhere to the putty. Prep done, I pour some Behlen powder in a plastic egg crate to double as a mixing trough. With tools and toothpicks at hand to serve as putty trowels, I add BSI Extra Thick Maxi-Cure CA to the powder and begin mixing. Well, if this were a science experiment it would remind me of my first chemistry set in 5th grade. Every 10-year-old with a new chemistry set sees the formula included for a ‘skunk bomb’ and tries it as his first experiment. I was no exception. After adding the glue to the powder and mixing, the mixture began to smoke and harden very quickly. After running the smoking egg crate to the bathroom and adding water to the mix, the smoke stopped and I return to the work table and record my science experiment with a picture capturing the toothpick forever encased in the hardened yellow putty. The pictures show the progression.

I first take 240 grit sanding paper and rough up the entire patch area to increase the bonding potential between the Bakelite and patch putty. Now, I construct a ‘slot mold’ for the button. The slot area is shaped like a concave canoe that the button edges encompass. I need to keep putty out of this area and form a mold of sorts for the putty. The results of this mold would remind one of the Wolverine in X-Men. As menacing as it appears, the center toothpick anchors the mold in the airhole and the ‘wing-picks’ are wedging the edges. The folded index card forming the mold I cover with smooth tape so it won’t adhere to the putty. Prep done, I pour some Behlen powder in a plastic egg crate to double as a mixing trough. With tools and toothpicks at hand to serve as putty trowels, I add BSI Extra Thick Maxi-Cure CA to the powder and begin mixing. Well, if this were a science experiment it would remind me of my first chemistry set in 5th grade. Every 10-year-old with a new chemistry set sees the formula included for a ‘skunk bomb’ and tries it as his first experiment. I was no exception. After adding the glue to the powder and mixing, the mixture began to smoke and harden very quickly. After running the smoking egg crate to the bathroom and adding water to the mix, the smoke stopped and I return to the work table and record my science experiment with a picture capturing the toothpick forever encased in the hardened yellow putty. The pictures show the progression.

Now fully in step with Jowal’s methodology of ‘Trial and Error’ progress, I ask the question, what happened? I’m not sure, but my guess is that I started with too much powder and adding the glue to it was not sufficient to keep it in liquid form. My guess is that the rapid hardening created the reactions (chemical energy!), which created the smoke, leading to my emergency procedures. This time I will approach the process like I do with a charcoal and super glue mix – put both powder and glue on an index card together and mix more gradually and see what happens. Well, I’ve proven that the methodology is not the culprit. Again, smoke was produced from the mixture on the index card while I started applying the putty to the stem. At this point, I’m thinking that the new glue I’m using might be the problem. I’ll try again with a glue I’ve used in the past. Thankfully, I could remove the hardened putty that did make it to the stem, by carefully scraping with my thumb nail. The bright side of this is that the color match with the stem looks great! Lesson 2 learned – what not to do. Pictures show the progression of lesson 2.

Now fully in step with Jowal’s methodology of ‘Trial and Error’ progress, I ask the question, what happened? I’m not sure, but my guess is that I started with too much powder and adding the glue to it was not sufficient to keep it in liquid form. My guess is that the rapid hardening created the reactions (chemical energy!), which created the smoke, leading to my emergency procedures. This time I will approach the process like I do with a charcoal and super glue mix – put both powder and glue on an index card together and mix more gradually and see what happens. Well, I’ve proven that the methodology is not the culprit. Again, smoke was produced from the mixture on the index card while I started applying the putty to the stem. At this point, I’m thinking that the new glue I’m using might be the problem. I’ll try again with a glue I’ve used in the past. Thankfully, I could remove the hardened putty that did make it to the stem, by carefully scraping with my thumb nail. The bright side of this is that the color match with the stem looks great! Lesson 2 learned – what not to do. Pictures show the progression of lesson 2.

While contemplating the next step, an email came in from Tim at J. H. Lowe in Ohio, and as expected, his note is very helpful:

While contemplating the next step, an email came in from Tim at J. H. Lowe in Ohio, and as expected, his note is very helpful:

The regular push-pull set is what you need. Are there threads inside the mortise? There are two sizes of these sets but the larger one is only used when the threads are very worn out and the oversize mortise part has to be fitted in the shank to fix this kind of worn out repair sleeve. I sell these by the each for $3 and by the dz. for a discounted price. You’ll need to change out the stem peg and the sleeve in the Meers pipe repair.

I responded by ordering 3 of each size so I’ll have some on hand for future projects. So, in a couple weeks, the new push-pull system order will arrive with a friend coming to visit Bulgaria. By that time, the rest of the Meerschaum Carved Vineyard should be ready and waiting with a quick finish to the restoration.

For the third go – I repeat roughing the patch area with 240 grit sanding paper to remove putty residue from Lesson 2. Then, after replacing Wolverine, I change glues using Hot Stuff Special ‘T’ CA glue and mix the same way that I did in Lesson 2, placing a puddle of glue alongside the Behlen Medium Yellow powder and gradually mix by drawing the powder into the glue until (hopefully) the mixture reaches a molasses like consistency. If it doesn’t ‘smoke’ this time, we’ll know the problem of Lessons 1 & 2.  Unfortunately, the ‘smoking’ is repeated and the putty hardened very quickly. My conclusion to the problem, and the pictures below show the progression of my solution. The problem is that I’m adding too much Behlen powder to the mix or not enough glue. I’m estimating that instead of a 50/50 mixture, I need an 80/20 ratio of glue to powder. I’m not sure of the chemistry involved, but the smoke produced happens when the mixture hardens. I had more time gradually to build up the patch with the greater glue ratio. Of course, the question remains, will the lesser powder content change the color match or texture? We’ll see. The pictures show the several cycles of building the patch around the button area. I had only so much time before the hardening would happen and I would make another small batch. The last picture shows the successfully removed Wolverine mold and the success of guarding the slot area from the putty.

Unfortunately, the ‘smoking’ is repeated and the putty hardened very quickly. My conclusion to the problem, and the pictures below show the progression of my solution. The problem is that I’m adding too much Behlen powder to the mix or not enough glue. I’m estimating that instead of a 50/50 mixture, I need an 80/20 ratio of glue to powder. I’m not sure of the chemistry involved, but the smoke produced happens when the mixture hardens. I had more time gradually to build up the patch with the greater glue ratio. Of course, the question remains, will the lesser powder content change the color match or texture? We’ll see. The pictures show the several cycles of building the patch around the button area. I had only so much time before the hardening would happen and I would make another small batch. The last picture shows the successfully removed Wolverine mold and the success of guarding the slot area from the putty.

The proof of this yellow pudding will be in the filing, sanding and shaping of the Behlen powder and superglue putty patch. I use needle files and 240 sanding paper to do the initial shaping. Starting from the slot side – the end of the stem, I like to create a baseline by re-establishing end by removing the excess. After removing excess putty on the end, I find the original button. Since the left side of the button needs to be totally rebuilt, as it was broken off, I use the remaining right side of the button and slot shape to help me form the left side of the slot so it will match.

The proof of this yellow pudding will be in the filing, sanding and shaping of the Behlen powder and superglue putty patch. I use needle files and 240 sanding paper to do the initial shaping. Starting from the slot side – the end of the stem, I like to create a baseline by re-establishing end by removing the excess. After removing excess putty on the end, I find the original button. Since the left side of the button needs to be totally rebuilt, as it was broken off, I use the remaining right side of the button and slot shape to help me form the left side of the slot so it will match.

With the baseline established, using the flat edge needle file, I begin to contour the general proportions of the button – lower then upper. The pictures show the gradual progress.

With the baseline established, using the flat edge needle file, I begin to contour the general proportions of the button – lower then upper. The pictures show the gradual progress.

With the general contours of the button established, I then score a line with the flat needle file to mark the upper button lip edge. With this edge established, I then file down the score line to establish the lip. I turn the file vertically and use the short edge as a saw and set the edge deeper. I like to have that edge established so that I can then begin to remove methodically the excess patch putty more accurately to the left of the lip on the second picture below. After removing as much of the excess putty as possible with the flat needle file, to avoid collateral filing into the Bakelite, I then use 240 grit paper to smooth the surface and remove the putty. The upper bit looks good so far! The pictures show the progress.

With the general contours of the button established, I then score a line with the flat needle file to mark the upper button lip edge. With this edge established, I then file down the score line to establish the lip. I turn the file vertically and use the short edge as a saw and set the edge deeper. I like to have that edge established so that I can then begin to remove methodically the excess patch putty more accurately to the left of the lip on the second picture below. After removing as much of the excess putty as possible with the flat needle file, to avoid collateral filing into the Bakelite, I then use 240 grit paper to smooth the surface and remove the putty. The upper bit looks good so far! The pictures show the progress.

I flip the stem over and repeat same process starting with defining the bit and creating a lip to guide the excess putty removal. While I work, I’m keeping an eye on the right side (lower in the picture below) of the stem where the major stem rebuild was. I recall Joyal’s observations of having to keep the patch high because during the smoothing and blending process sanding on the edge of the patch was taking too much of the stem material in the process. He then described having to refill with more patch the ‘border’ between patch and stem. The pictures show the progress on the lower bit area.

I flip the stem over and repeat same process starting with defining the bit and creating a lip to guide the excess putty removal. While I work, I’m keeping an eye on the right side (lower in the picture below) of the stem where the major stem rebuild was. I recall Joyal’s observations of having to keep the patch high because during the smoothing and blending process sanding on the edge of the patch was taking too much of the stem material in the process. He then described having to refill with more patch the ‘border’ between patch and stem. The pictures show the progress on the lower bit area.

The next two pictures show the completion of the filing and use of 240 grit sanding paper. I then use 600 grit paper to smooth and blend more and finish with briskly rubbing with 0000 steel wool. At this stage of the stem repair, I look at the patch areas (3rd picture) and the use of Behlen Furniture Powder Medium Yellow and Special ‘T’ CA glue is strong. Building up the chip area and missing button portion wasn’t easy but it looks good. The color is good though it has a speckled quality to it created by small air pockets in the patch which were exposed during the sanding. This I have found is normal. To fill the pockets, I apply a dab of Hot Stuff CA glue on the stem patch and then ‘paint’ it over the patch using a toothpick. I do the same with the button lips – upper and lower. I repeat sanding with 600 grit and then steel wool (I forgot to take pictures of filling the air pockets!). The pictures show the progress.

The next two pictures show the completion of the filing and use of 240 grit sanding paper. I then use 600 grit paper to smooth and blend more and finish with briskly rubbing with 0000 steel wool. At this stage of the stem repair, I look at the patch areas (3rd picture) and the use of Behlen Furniture Powder Medium Yellow and Special ‘T’ CA glue is strong. Building up the chip area and missing button portion wasn’t easy but it looks good. The color is good though it has a speckled quality to it created by small air pockets in the patch which were exposed during the sanding. This I have found is normal. To fill the pockets, I apply a dab of Hot Stuff CA glue on the stem patch and then ‘paint’ it over the patch using a toothpick. I do the same with the button lips – upper and lower. I repeat sanding with 600 grit and then steel wool (I forgot to take pictures of filling the air pockets!). The pictures show the progress.

With the repairs to the stem completed, using micromesh pads 1500 to 2400 I wet sand the stem. Following this, I dry sand the stem using pads 3200 to 4000 and then, 6000 to 12000. The Bakelite (or Amberoid, I’ll have to figure out how to tell the difference) stem gradually shines up nicely with each successive micromesh cycle. The pictures show the progress.

With the repairs to the stem completed, using micromesh pads 1500 to 2400 I wet sand the stem. Following this, I dry sand the stem using pads 3200 to 4000 and then, 6000 to 12000. The Bakelite (or Amberoid, I’ll have to figure out how to tell the difference) stem gradually shines up nicely with each successive micromesh cycle. The pictures show the progress. I follow the micromesh cycles with applying Blue Diamond compound to the stem with the cotton cloth Dremel wheel set to the slowest speed. I then mount the carnauba cotton cloth wheel on the Dremel and give the stem 3 coats of carnauba wax. I follow the carnauba with a hand-buff using a microfiber cloth. Wow! I like it. The Bakelite or Amberoid has the appearance of glass – the patch has no textural differences with the original stem. The last two pictures are flipped to show what I’m seeing after the buff. Stem completed for now – the new push-pull tenon system should be in transit.

I follow the micromesh cycles with applying Blue Diamond compound to the stem with the cotton cloth Dremel wheel set to the slowest speed. I then mount the carnauba cotton cloth wheel on the Dremel and give the stem 3 coats of carnauba wax. I follow the carnauba with a hand-buff using a microfiber cloth. Wow! I like it. The Bakelite or Amberoid has the appearance of glass – the patch has no textural differences with the original stem. The last two pictures are flipped to show what I’m seeing after the buff. Stem completed for now – the new push-pull tenon system should be in transit.

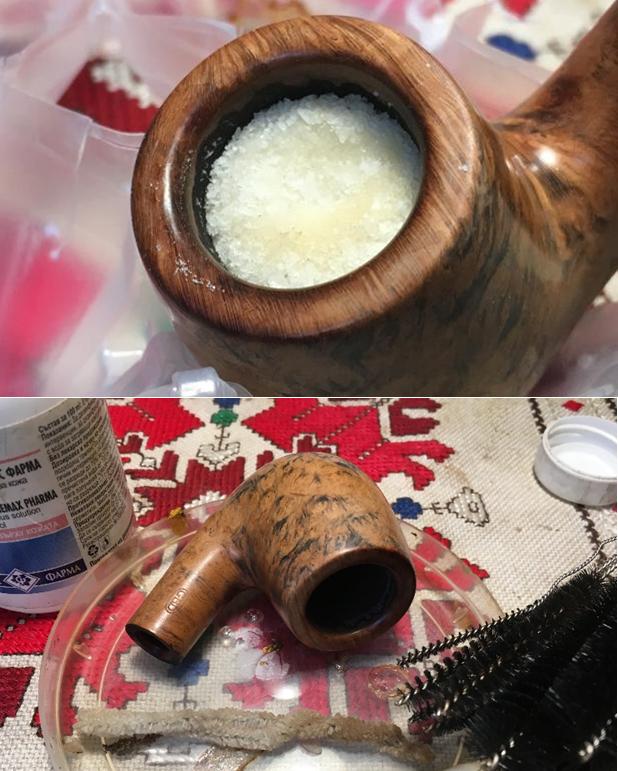

With the stem completed and on hold for the tenon, I look to complete the stummel of this Meer Carved Vineyard. With of the unique characteristics of Meerschaum pipes, they’re like wine – they get better with age! For Meerschaums, their value increases with use as the oils in the tobacco interact with the unique composition of the Meerschaum the bowl will change color gradually, darkening to the golden, honey brown which is its patina. The Carved Vineyard displays this growing patina and to enhance this natural coloring process, treating the stummel with bees’ wax is the long-used practice of choice. This is my first application of bee’s wax to a Meer and Charles Lemon’s, of Dad’s Pipes, descriptive posts have been helpful as I’ve done my research (See: Quick Clean-up of a Tulip Meerschaum Sitter). One thing very much available in Bulgaria is bees’ wax, which I found in a local outdoor market at the honey kiosk. My price was 3BGN for 100gr (Translation: $1.63 for 1/5 pounds). I don’t know if it’s a deal or a steal.

With the stem completed and on hold for the tenon, I look to complete the stummel of this Meer Carved Vineyard. With of the unique characteristics of Meerschaum pipes, they’re like wine – they get better with age! For Meerschaums, their value increases with use as the oils in the tobacco interact with the unique composition of the Meerschaum the bowl will change color gradually, darkening to the golden, honey brown which is its patina. The Carved Vineyard displays this growing patina and to enhance this natural coloring process, treating the stummel with bees’ wax is the long-used practice of choice. This is my first application of bee’s wax to a Meer and Charles Lemon’s, of Dad’s Pipes, descriptive posts have been helpful as I’ve done my research (See: Quick Clean-up of a Tulip Meerschaum Sitter). One thing very much available in Bulgaria is bees’ wax, which I found in a local outdoor market at the honey kiosk. My price was 3BGN for 100gr (Translation: $1.63 for 1/5 pounds). I don’t know if it’s a deal or a steal.  After I unwrap the package, I break off some chunks of the bee’s wax and put them in a small mason jar, which I’ll be able to keep unused wax for the next Meer treatment. Using my hot air gun, I melt the wax in the mason jar. After melting the wax, I hold the Meer over the hot gun to warm up to better absorb the wax. Blame it on Bulgarian winters, but when I finish warming the Meer, the wax has already cooled down and congealing! So, a more rapid wax melting follows, and a re-warming of the Meer stummel. I used a Q-tip cotton swab to paint the bowl with the melted bee’s wax. I was careful to paint the sculpted vineyard lines – getting the wax in the nooks and crannies. I put the stummel aside to cool. Since this was my first time to apply the bee’s wax treatment to a Meer, I was a little surprised how thick the congealed wax was on the stummel after it cooled. It could be that the Meer wasn’t hot enough and the wax was cooling too quickly. Either way, the Meer received a treatment! After cooled, I try buffing with a towel to remove the thicker waxy residue, and I discover that it’s not too easy. I’m thinking that the wax is too thick and it congealed to fast (3rd picture below). I improvise and I think the improvisation benefited this Meer. Using a Q-tip as a brush, I start passing the thick-layered bees’ wax stummel over the air gun – like passing over a lit candle, it liquefies the wax on the portion impacted by the heat. As the wax liquefies, I paint it into the surface – working it in well and removing the excess with the Q-tip. This time applying wax around the Meerschaum seems to absorb the wax instead of being smothered by it. It didn’t take long and the application of bees’ wax is complete (4th picture below)! Then, before the stummel cooled down, while yet warm, I buff the stummel with a towel and then with a microfiber cloth and WOW. I’m a believer. The shine and deepening of the patina is evident! The pictures tell the story.

After I unwrap the package, I break off some chunks of the bee’s wax and put them in a small mason jar, which I’ll be able to keep unused wax for the next Meer treatment. Using my hot air gun, I melt the wax in the mason jar. After melting the wax, I hold the Meer over the hot gun to warm up to better absorb the wax. Blame it on Bulgarian winters, but when I finish warming the Meer, the wax has already cooled down and congealing! So, a more rapid wax melting follows, and a re-warming of the Meer stummel. I used a Q-tip cotton swab to paint the bowl with the melted bee’s wax. I was careful to paint the sculpted vineyard lines – getting the wax in the nooks and crannies. I put the stummel aside to cool. Since this was my first time to apply the bee’s wax treatment to a Meer, I was a little surprised how thick the congealed wax was on the stummel after it cooled. It could be that the Meer wasn’t hot enough and the wax was cooling too quickly. Either way, the Meer received a treatment! After cooled, I try buffing with a towel to remove the thicker waxy residue, and I discover that it’s not too easy. I’m thinking that the wax is too thick and it congealed to fast (3rd picture below). I improvise and I think the improvisation benefited this Meer. Using a Q-tip as a brush, I start passing the thick-layered bees’ wax stummel over the air gun – like passing over a lit candle, it liquefies the wax on the portion impacted by the heat. As the wax liquefies, I paint it into the surface – working it in well and removing the excess with the Q-tip. This time applying wax around the Meerschaum seems to absorb the wax instead of being smothered by it. It didn’t take long and the application of bees’ wax is complete (4th picture below)! Then, before the stummel cooled down, while yet warm, I buff the stummel with a towel and then with a microfiber cloth and WOW. I’m a believer. The shine and deepening of the patina is evident! The pictures tell the story.

With the Meerschaum’s stem and stummel complete – almost – I set both aside waiting for the arrival of the push-pull tenon from the US. I’m beginning to wonder whether this Meer Carved Vineyard should go to The Pipe Steward store, or remain in my collection – often I have that problem 🙂 !

With the Meerschaum’s stem and stummel complete – almost – I set both aside waiting for the arrival of the push-pull tenon from the US. I’m beginning to wonder whether this Meer Carved Vineyard should go to The Pipe Steward store, or remain in my collection – often I have that problem 🙂 !

A few weeks later the push-pull tenons arrive via a friend who was willing to carry them to Bulgaria. I open the package sent by Tim West at J.H. Lowe in Columbus, Ohio, and have my first look at what a new push-pull system looks like. I unscrew the old tenon and easily screw the new one in place. The mortise sleeve’s threads worked perfectly as well. The problem though, is that it will not screw all the way in. Previously, I identified a tubing of sorts deeper in the mortise which was the only thing the old tenon was locking into – though poorly. My first inclination was to cut the new mortise tenon sleeve so that being shortened it would fit in the limited space. It was then that I started questioning whether what I was looking at was part of the design or that it was in fact, the left-over remains of the bottom end of the old mortise sleeve which had broken off. After looking closely at the inner tubing, I can see fragments of the old break. Ok! Now I understand that I need to exorcise this vagabond mortise sleeve. I first try wedging a small flat head screw driver in the tubing to ‘unscrew’ it by turning it counter-clockwise. I was hoping that it might be loose, but will not budge. So, using appropriately size drill bits and wood screws, gradually I clear out the obstructing portion by shaving off the material of the old sleeve which I think might be acrylic. I am careful to keep the bits and screws straight so they do not nick the Meer threads. This was not an easy or fast process, but eventually I was satisfied to remove most of the old sleeve – leaving only a very thin ‘skin’ over the threaded area deeper in the mortise, which may indeed help in keeping the mortise cleaner. After this, I screw the new insert into the mortise and trim and sand the protruding ‘head’ of the sleeve to improve the fit and alignment of the mortise and stem. I also sand down the tenon diameter to improve its fit into the sleeve. I’m pleased with the results. The pictures show the replacement of the push-pull tenon system.

I’m pleased with the stem rebuild that has blended very well with the Bakelite stem and has put this Meerschaum back in service for a new steward. The patina of the Meerschaum Carved Vineyard has a very healthy start and will only season more with good, aromatic tobaccos. I also like the blending of smooth and carved Meerschaum – a very stylish pipe. If you would like to adopt this Meerschaum Carved Vineyard, look at the Pipe Store in my new blog site at ThePipeSteward.com. The profits of my pipe sales go to help women and children who have been sexually exploited and trafficked through the Daughters of Bulgaria, an organization we work with here in Bulgaria. Thanks for joining me!

I’m pleased with the stem rebuild that has blended very well with the Bakelite stem and has put this Meerschaum back in service for a new steward. The patina of the Meerschaum Carved Vineyard has a very healthy start and will only season more with good, aromatic tobaccos. I also like the blending of smooth and carved Meerschaum – a very stylish pipe. If you would like to adopt this Meerschaum Carved Vineyard, look at the Pipe Store in my new blog site at ThePipeSteward.com. The profits of my pipe sales go to help women and children who have been sexually exploited and trafficked through the Daughters of Bulgaria, an organization we work with here in Bulgaria. Thanks for joining me!

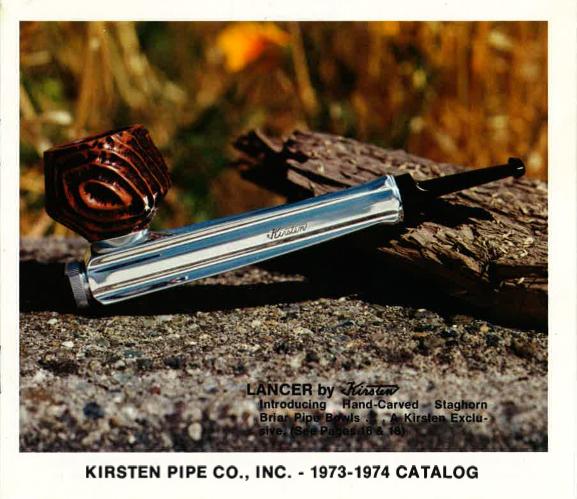

The other interesting thing about the eBay offering was its marking. The left shank side reads “REJECT” over “LONDONMADE”. The only lead I found for this “REJECT” stamping was in ‘Who Made That Pipe?’ by Herb Wilzak and Tom Colwell, which provided only one reference to “Reject” as belonging to the W. H. Carrington Co. started in 1891 by William Henry Carrington in Manchester, England. This came from the brief Pipedia article which also states that after a century of operation it went out of business. I found more information in a Pipes Magazine Forum thread but the source of the information was not cited.

The other interesting thing about the eBay offering was its marking. The left shank side reads “REJECT” over “LONDONMADE”. The only lead I found for this “REJECT” stamping was in ‘Who Made That Pipe?’ by Herb Wilzak and Tom Colwell, which provided only one reference to “Reject” as belonging to the W. H. Carrington Co. started in 1891 by William Henry Carrington in Manchester, England. This came from the brief Pipedia article which also states that after a century of operation it went out of business. I found more information in a Pipes Magazine Forum thread but the source of the information was not cited.

The question that begs asking is what is ‘Reject’ about this pipe? Overall, it’s in good shape. The chamber has very mild cake build up, and the stummel surface shows some small fills and usual dents of wear. The stem has been cleaned, it seems, very little chatter or oxidation. I only detect two issues as I look at the Reject London Made. First, the finish on the stummel is shiny and acrylic-like, which, to me, hides the natural briar. It is cloudy and I’ll remove it and work on the broad landscape of this stummel real estate to bring out the briar. I like this challenge! The other issue is the stem – it is under-clocked and a bit catawampus. I will heat the vulcanite and restore a good bend in alignment with the pipe. The reason this pipe was stamped ‘Reject’ coming out of the factory is a mystery to me unless it was destined to be a higher end pipe and the briar had too many imperfections…. Only conjecture and I would appreciate anyone’s input on this.

The question that begs asking is what is ‘Reject’ about this pipe? Overall, it’s in good shape. The chamber has very mild cake build up, and the stummel surface shows some small fills and usual dents of wear. The stem has been cleaned, it seems, very little chatter or oxidation. I only detect two issues as I look at the Reject London Made. First, the finish on the stummel is shiny and acrylic-like, which, to me, hides the natural briar. It is cloudy and I’ll remove it and work on the broad landscape of this stummel real estate to bring out the briar. I like this challenge! The other issue is the stem – it is under-clocked and a bit catawampus. I will heat the vulcanite and restore a good bend in alignment with the pipe. The reason this pipe was stamped ‘Reject’ coming out of the factory is a mystery to me unless it was destined to be a higher end pipe and the briar had too many imperfections…. Only conjecture and I would appreciate anyone’s input on this.

I like working on a clean pipe so I work on the internals using cotton swabs and pipe cleaners dipped in isopropyl 95%. With very little effort the mortise and draft are clean.

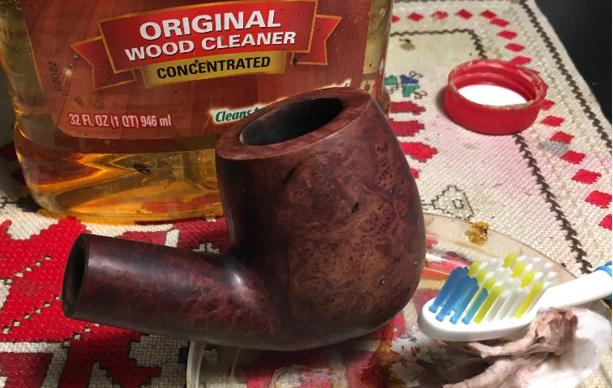

I like working on a clean pipe so I work on the internals using cotton swabs and pipe cleaners dipped in isopropyl 95%. With very little effort the mortise and draft are clean. Moving to the external stummel surface, I use Murphy’s Soap undiluted with cotton pads and a bristled tooth brush to clean the grime off. The Murphy’s Soap does a good job removing the old shiny finish.

Moving to the external stummel surface, I use Murphy’s Soap undiluted with cotton pads and a bristled tooth brush to clean the grime off. The Murphy’s Soap does a good job removing the old shiny finish. Looking closely at the surface, the dent I saw earlier I want to remove using the iron approach, that I have yet to try, but this dent looks like a good candidate. I’ve read several other restorations where this method was used. Using a heated clothes iron, I use a wet wash cloth and lay it over the dent area and then I apply the iron to that point. The concept is based upon the water content of wood being heated and absorbing the water and expanding the dented area – wood is a sponge-like material when wet. I apply the iron several times and gradually I see the severity of the dent lessening with each heat application. I can still see the dent but it should be more easily removed using a sanding sponge.

Looking closely at the surface, the dent I saw earlier I want to remove using the iron approach, that I have yet to try, but this dent looks like a good candidate. I’ve read several other restorations where this method was used. Using a heated clothes iron, I use a wet wash cloth and lay it over the dent area and then I apply the iron to that point. The concept is based upon the water content of wood being heated and absorbing the water and expanding the dented area – wood is a sponge-like material when wet. I apply the iron several times and gradually I see the severity of the dent lessening with each heat application. I can still see the dent but it should be more easily removed using a sanding sponge.

Using a medium and light grade sanding sponge I work on the stummel to remove the minor wear nicks and dents on the surface. I like a softer edge on the inner rim lip so I introduce a gentle bevel both to give it a softer look and to remove some scorched areas. I think an inner bevel adds a bit of class as well. I first use a coarser 120 grit paper to cut the bevel then I follow with 240 grit and 600 grit paper to smooth and blend the bevel. The pictures show the progress.

Using a medium and light grade sanding sponge I work on the stummel to remove the minor wear nicks and dents on the surface. I like a softer edge on the inner rim lip so I introduce a gentle bevel both to give it a softer look and to remove some scorched areas. I think an inner bevel adds a bit of class as well. I first use a coarser 120 grit paper to cut the bevel then I follow with 240 grit and 600 grit paper to smooth and blend the bevel. The pictures show the progress.

I now turn to the micromesh pad cycles. Using pads 1500 to 2400 I wet sand the stummel followed by dry sanding with pads 3200 to 4000 and then 6000 to 12000. Throughout the sanding, I’m careful to avoid the Reject markings. The grain is looking good. The pictures show the progress.

I now turn to the micromesh pad cycles. Using pads 1500 to 2400 I wet sand the stummel followed by dry sanding with pads 3200 to 4000 and then 6000 to 12000. Throughout the sanding, I’m careful to avoid the Reject markings. The grain is looking good. The pictures show the progress.

I put the stummel aside and fish the stem out of the Oxy-Clean bath. Very little oxidation has surfaced. I use 600 grit paper and wet sand the stem followed by sand buffing the stem with 0000 steel wool. The pictures show the progress.

I put the stummel aside and fish the stem out of the Oxy-Clean bath. Very little oxidation has surfaced. I use 600 grit paper and wet sand the stem followed by sand buffing the stem with 0000 steel wool. The pictures show the progress. Before I proceed further with the internal cleaning of the stem and the external polishing, I want to correct the bend of the stem. With great difficulty, I am able finally to pass a smooth pipe cleaner through the stem. The pipe cleaner helps to maintain the airway integrity while I heat and re-bend the stem. Using the heat gun to heat the stem, I turn the stem to apply the heat evenly over the stem to soften the vulcanite making it pliable. I then straighten both the stem clock-wise to correct the under-clocking. While still pliable I re-establish the bend over a block of wood and set the new shape under cool tap water. The first time around, the button was still not ‘clocked’ to my satisfaction. I reheated and made the additional adjustment and again, set the shape under cool tap water. I reattach stem and stummel to eyeball things and the newly aligned stem bend and clocked button look good. I take pictures to chronicle the progress with the stem.

Before I proceed further with the internal cleaning of the stem and the external polishing, I want to correct the bend of the stem. With great difficulty, I am able finally to pass a smooth pipe cleaner through the stem. The pipe cleaner helps to maintain the airway integrity while I heat and re-bend the stem. Using the heat gun to heat the stem, I turn the stem to apply the heat evenly over the stem to soften the vulcanite making it pliable. I then straighten both the stem clock-wise to correct the under-clocking. While still pliable I re-establish the bend over a block of wood and set the new shape under cool tap water. The first time around, the button was still not ‘clocked’ to my satisfaction. I reheated and made the additional adjustment and again, set the shape under cool tap water. I reattach stem and stummel to eyeball things and the newly aligned stem bend and clocked button look good. I take pictures to chronicle the progress with the stem.

I now clean the internals of the stem using pipe cleaners dipped in isopropyl 95%. The stem is clean but I find that even though I’ve re-bent the stem the pipe cleaners will not move through the bend of the stem. I decide to open the slot area with a round pointed needle file moving it back and forth in the slot. After this, I take a drill bit, smaller than the slot opening, and insert it into the airway rotating it against the edges of the airway hoping to expand the internal airway area as it enters the slot. This seems to help yet the bend is still tight on the pipe cleaners, but they are passing through. The stem is clean. The pictures show the progress.

I now clean the internals of the stem using pipe cleaners dipped in isopropyl 95%. The stem is clean but I find that even though I’ve re-bent the stem the pipe cleaners will not move through the bend of the stem. I decide to open the slot area with a round pointed needle file moving it back and forth in the slot. After this, I take a drill bit, smaller than the slot opening, and insert it into the airway rotating it against the edges of the airway hoping to expand the internal airway area as it enters the slot. This seems to help yet the bend is still tight on the pipe cleaners, but they are passing through. The stem is clean. The pictures show the progress.

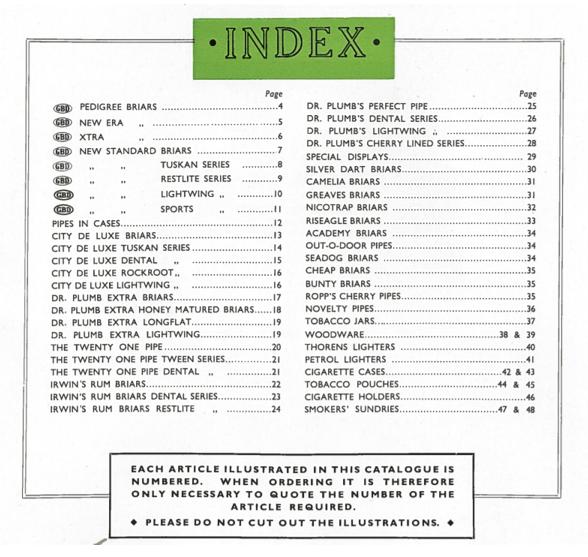

Time to bring out the micromesh pads to finish the stem. With pads 1500 to 2400 I wet sand the stem. I follow by dry sanding with pads 3200 to 4000 and then 6000 to 12000. With each set of 3 I apply Obsidian Oil to the stem to revitalize the vulcanite, and I love to see the pop of the vulcanite as it moves through the micromesh cycles! I put the stem aside to dry. The pictures show the progress.

Time to bring out the micromesh pads to finish the stem. With pads 1500 to 2400 I wet sand the stem. I follow by dry sanding with pads 3200 to 4000 and then 6000 to 12000. With each set of 3 I apply Obsidian Oil to the stem to revitalize the vulcanite, and I love to see the pop of the vulcanite as it moves through the micromesh cycles! I put the stem aside to dry. The pictures show the progress.

Turning back to the stummel, I decide to apply Fiebing’s Dark Brown Leather Dye to the Reject London Made to emulate the darker hues of the original finish. Since it is an aniline dye, I can lighten the finish to taste by wiping the stained stummel with cotton pads wetted with isopropyl. The large stummel has a lot of briar real estate to show off with a smattering of different grains – pleasing to the eye and a handful of stummel to boot! I just acquired Fiebing’s Black Leather Dye and I decide to experiment. I will add a touch of it to the dark brown to create the blend. The first snag I run into is that this is the largest stummel I’ve worked on and my usual corks that I use to prop the stummel on the candle stick during the staining process were too small. I rummaged through our cork supply and found only one large enough. I warm the stummel to expand the briar enabling the dye to absorb better into the grain. I apply the dye liberally over the surface with a pipe cleaner folded over. Then I fire the wet dye and the alcohol content burns off setting the stain. I repeat the process again to assure total coverage and set the stummel aside to rest.

Turning back to the stummel, I decide to apply Fiebing’s Dark Brown Leather Dye to the Reject London Made to emulate the darker hues of the original finish. Since it is an aniline dye, I can lighten the finish to taste by wiping the stained stummel with cotton pads wetted with isopropyl. The large stummel has a lot of briar real estate to show off with a smattering of different grains – pleasing to the eye and a handful of stummel to boot! I just acquired Fiebing’s Black Leather Dye and I decide to experiment. I will add a touch of it to the dark brown to create the blend. The first snag I run into is that this is the largest stummel I’ve worked on and my usual corks that I use to prop the stummel on the candle stick during the staining process were too small. I rummaged through our cork supply and found only one large enough. I warm the stummel to expand the briar enabling the dye to absorb better into the grain. I apply the dye liberally over the surface with a pipe cleaner folded over. Then I fire the wet dye and the alcohol content burns off setting the stain. I repeat the process again to assure total coverage and set the stummel aside to rest.

After several hours, I ‘unwrap’ the fired stummel using the Dremel mounted with a felt buffing wheel. With the Dremel at its slowest speed, I move methodically over the stummel applying Tripoli compound to remove the crusted fired surface. I don’t apply too much downward pressure on the briar but I allow the RPMs and the compound to do the work for me. After completed, I use cotton pads wetted with alcohol to wipe down the stummel to lighten the stained finish and to blend the dye. After this, I mount a cotton cloth wheel on the Dremel and apply Blue Diamond compound and methodically work the wheel over the entire surface. After completed, I again wipe the stummel with cotton pads wetted with isopropyl 95%. I follow this by doing another quick tour over the stummel with the Blue Diamond. The use of black dye with the dark brown has the effect of darkening the grain which I’m liking as I see the grain surfacing through the compound cycles. The pictures show the progress.

After several hours, I ‘unwrap’ the fired stummel using the Dremel mounted with a felt buffing wheel. With the Dremel at its slowest speed, I move methodically over the stummel applying Tripoli compound to remove the crusted fired surface. I don’t apply too much downward pressure on the briar but I allow the RPMs and the compound to do the work for me. After completed, I use cotton pads wetted with alcohol to wipe down the stummel to lighten the stained finish and to blend the dye. After this, I mount a cotton cloth wheel on the Dremel and apply Blue Diamond compound and methodically work the wheel over the entire surface. After completed, I again wipe the stummel with cotton pads wetted with isopropyl 95%. I follow this by doing another quick tour over the stummel with the Blue Diamond. The use of black dye with the dark brown has the effect of darkening the grain which I’m liking as I see the grain surfacing through the compound cycles. The pictures show the progress. To remove the compound dust, I hand buff the stummel with a flannel cloth. After mounting the Dremel with a cotton cloth wheel and increasing the speed to 2, one notch over the slowest, I apply several coats of carnauba wax to the stummel and reattached stem. I follow this with a rigorous hand buffing with a micromesh cloth. When I experimented by adding black dye to the dark brown I didn’t anticipate the unique hue that would result. The briar grain veins seem to have latched on to the black and the lighter grains came out with a golden/copper kettle blend that is striking – very interesting and attractive. If this REJECT – LONDON MADE is a product of the W. H. Carrington Co., I cannot say why it received this factory stamp. For those who like huge pipes that fill the hand, this big boy, bent billiard fits the bill and needs a new steward! All the profits of pipes I sell help the Daughters of Bulgaria, an organization we work with that helps women and children who have been trafficked and sexually exploited. If you’re interested in this REJECT, hop over to my blog site, The Pipe Steward. Thanks for joining me!

To remove the compound dust, I hand buff the stummel with a flannel cloth. After mounting the Dremel with a cotton cloth wheel and increasing the speed to 2, one notch over the slowest, I apply several coats of carnauba wax to the stummel and reattached stem. I follow this with a rigorous hand buffing with a micromesh cloth. When I experimented by adding black dye to the dark brown I didn’t anticipate the unique hue that would result. The briar grain veins seem to have latched on to the black and the lighter grains came out with a golden/copper kettle blend that is striking – very interesting and attractive. If this REJECT – LONDON MADE is a product of the W. H. Carrington Co., I cannot say why it received this factory stamp. For those who like huge pipes that fill the hand, this big boy, bent billiard fits the bill and needs a new steward! All the profits of pipes I sell help the Daughters of Bulgaria, an organization we work with that helps women and children who have been trafficked and sexually exploited. If you’re interested in this REJECT, hop over to my blog site, The Pipe Steward. Thanks for joining me!