by Kenneth Lieblich

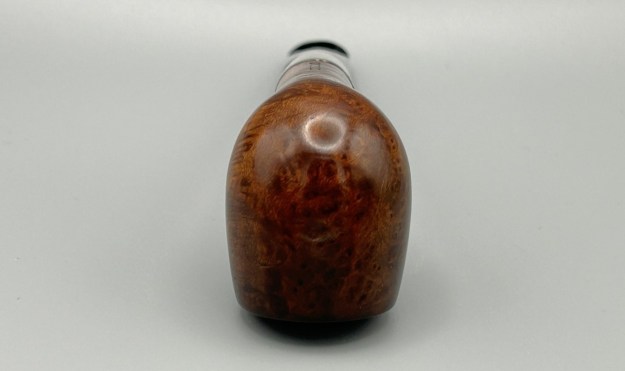

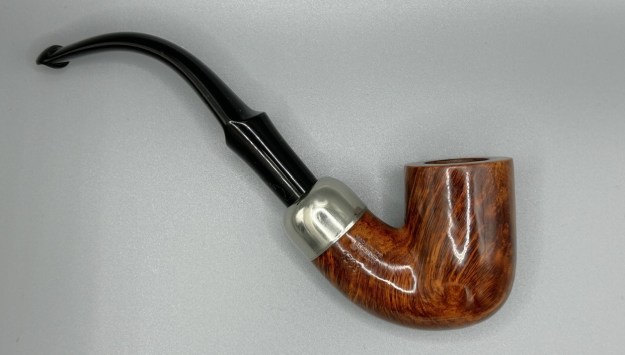

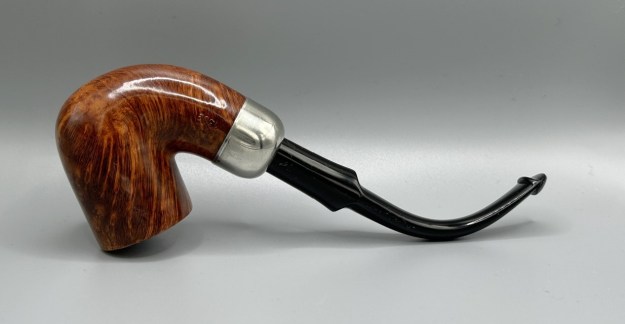

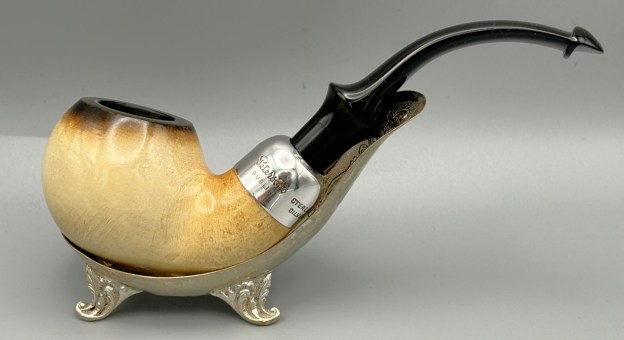

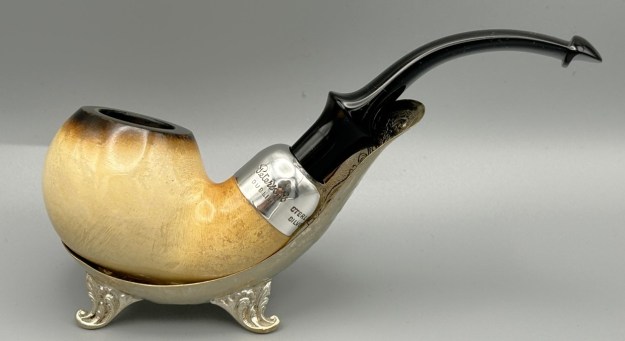

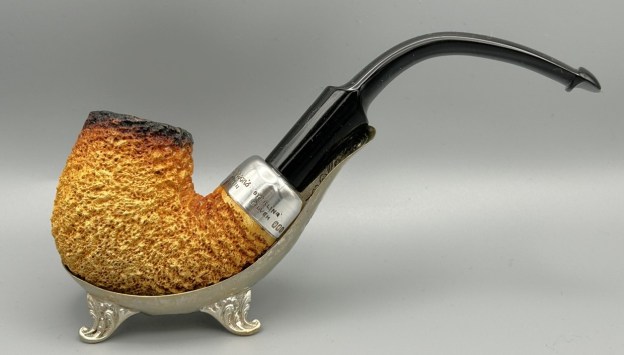

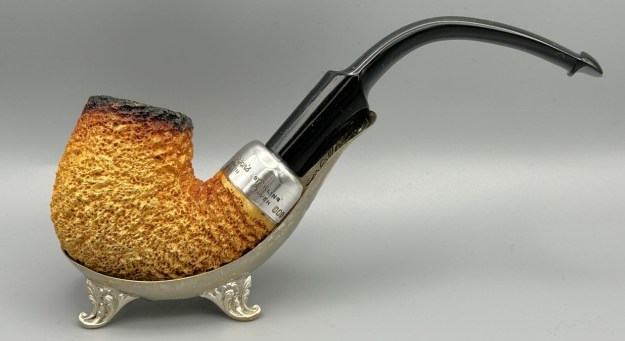

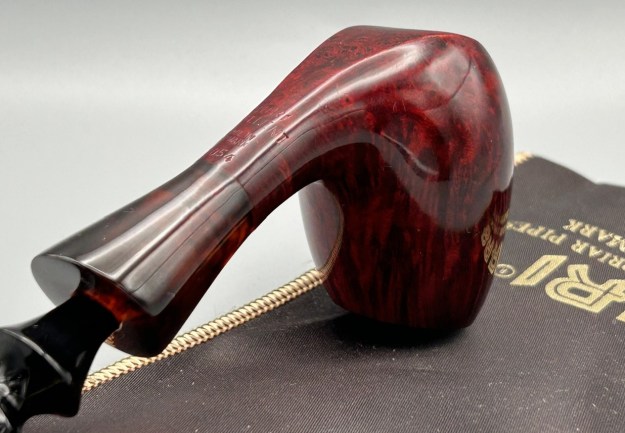

Next on my workbench is a pipe that has been in my boxes for a long, long time. But there comes a time when a pipe calls out and wants to be restored. That’s what happened for this charming bulldog, made by the American pipe house, Edward’s. It has an interesting rustication on the bowl and a variegated acrylic stem which complements the stummel well. I always thought highly of this dapper pipe and I’m sorry to see it go, but happy to give it new life in someone else’s hands.

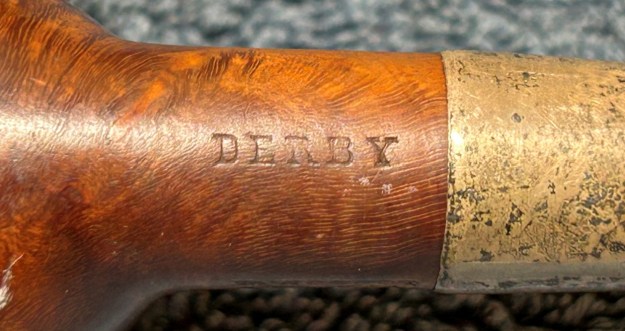

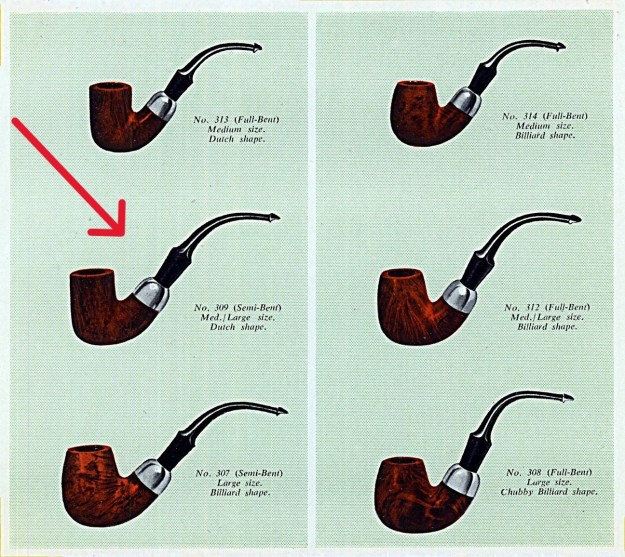

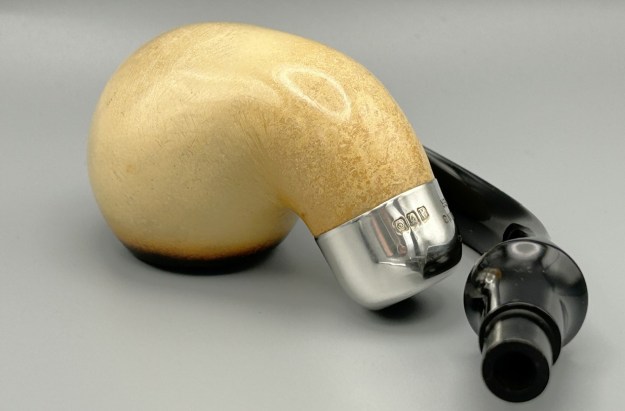

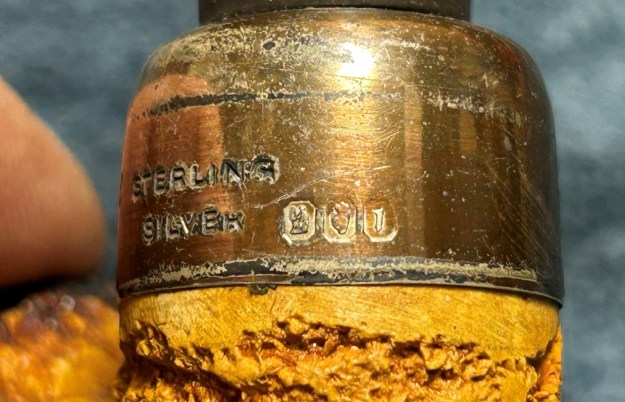

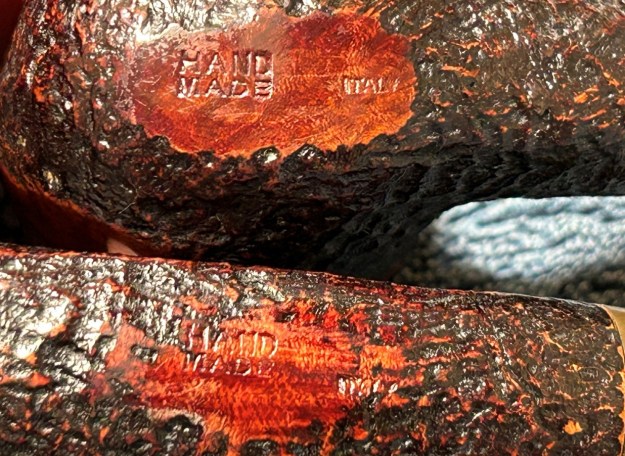

Let’s look at the markings. On the right topside of the shank, we see Edward’s. On the left underside of the shank, we see Algerian Briar [over] 20. I can only assume that the number 20 is a shape number, but wasn’t able to find any official confirmation of that. No markings on the stem.

Let’s look at the markings. On the right topside of the shank, we see Edward’s. On the left underside of the shank, we see Algerian Briar [over] 20. I can only assume that the number 20 is a shape number, but wasn’t able to find any official confirmation of that. No markings on the stem. I knew about Edward’s, but thought it was a good idea to refresh my memory. At Pipephil, they provided this tidbit of information:

I knew about Edward’s, but thought it was a good idea to refresh my memory. At Pipephil, they provided this tidbit of information:

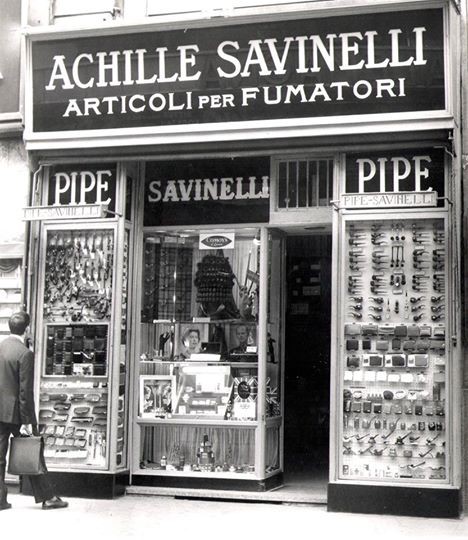

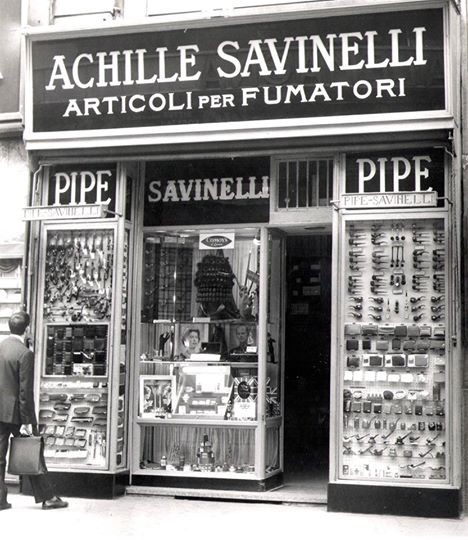

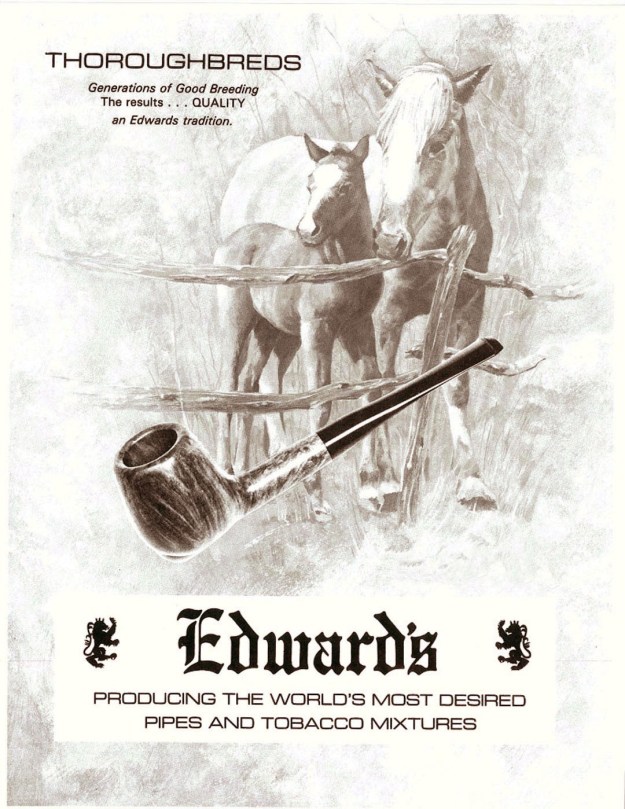

Edward’s Pipes, headquartered in Tampa, FL, got its start importing pipes from France and continued to do so from 1958 to 1963 when it started producing pipes in Florida from prime Algerian Briar, a practice they continue to this day (2010). Randy Wiley, pipecarver in the USA, got his start at Edward’s.

At Pipedia, they write the following:

Edward’s pipes were originally produced in Saint-Claude, France when Francais [sic] actually was a world-class pipe maker with longstanding business & political connections to Colonial Algeria that allowed them to obtain the finest briar. During the tumultuous 1960’s, Edward’s created a business model to offer the finest briar available in both Classic and Freehand shapes – all at a fair price. They bought the company & equipment and cornered the market on the finest, choice Algerian Briar just before the supply vanished in political turmoil of Algeria’s independence. Edward’s packed up both machinery and briar-treasure to America, safely caching the essentials to create a new pipe-making dynasty. This was a coup, for the 70’s and 80’s were grim years for pipe smokers as quality briar all but disappeared. Edward’s Design Philosophy is hard to pin down, think of their style as the “American Charatan” with unique & clever twists all their own. Today, they fashion pipes in several locations across the USA. All of Edward’s pipes are Algerian Briar – a fact very few pipe companies can claim, and all are oil-cured utilizing natural finishes – no strange concoctions are used to interfere in your tastebud’s dance with the briar. Algerian, Calabrian, Sardinian, Corsican – take your pick, but Algerian Briar is generally considered the finest smoking briar ever used. When combined with oil-curing, Algerian takes on a magical quality that even Alfred Dunhill recognized as far back as 1918 as the choice for both his Bruyere and Shell. How about the condition? The stummel is in very good condition – the pipe was well maintained. There is a bit of cake in the bowl and lava on the rim, but truly not that much. There is a noticeable fill on the front of the bowl, but I am happy to leave that as it is. The stem is a bit trickier. It’s dirty – although no more than average. However, the previous owner must have been a clencher. There are some serious chomp marks in this stem, but I can resolve that.

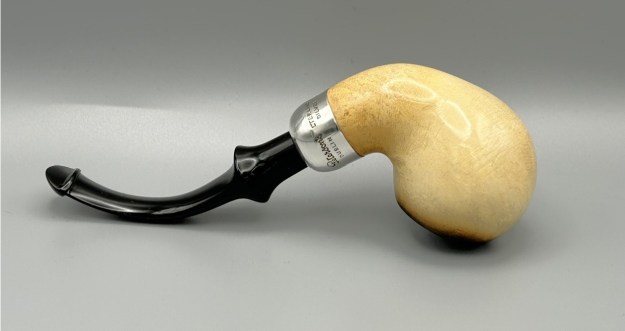

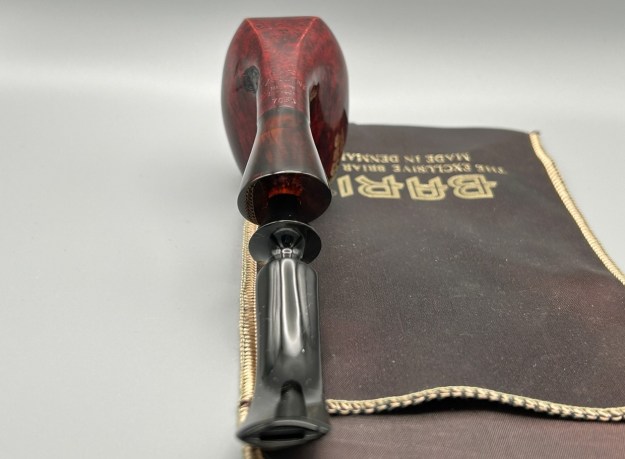

How about the condition? The stummel is in very good condition – the pipe was well maintained. There is a bit of cake in the bowl and lava on the rim, but truly not that much. There is a noticeable fill on the front of the bowl, but I am happy to leave that as it is. The stem is a bit trickier. It’s dirty – although no more than average. However, the previous owner must have been a clencher. There are some serious chomp marks in this stem, but I can resolve that.

I used isopropyl alcohol on a few cotton rounds and wiped down the stem to provide an initial cleaning of filth before moving on to the next steps. The primary cleaning came next. I disinfected the inside of the stem with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. I scrubbed thoroughly to make sure the interior was very clean. However, I also used some tube brushes and cream cleanser to really scrub the insides. That helped!

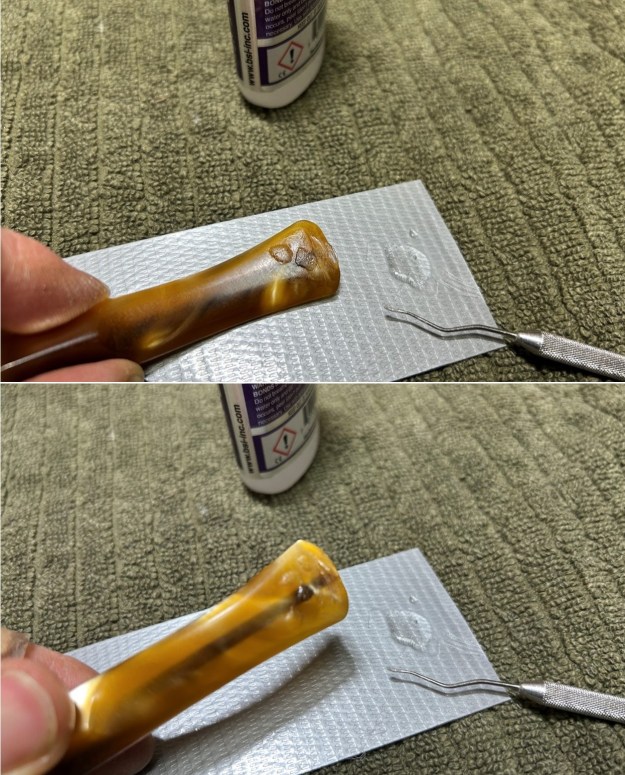

I used isopropyl alcohol on a few cotton rounds and wiped down the stem to provide an initial cleaning of filth before moving on to the next steps. The primary cleaning came next. I disinfected the inside of the stem with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. I scrubbed thoroughly to make sure the interior was very clean. However, I also used some tube brushes and cream cleanser to really scrub the insides. That helped!  Since this stem was made of acrylic, there’s no oxidation and I can skip those steps and go right to repair. I set about fixing the marks and dents in the acrylic – of which there were quite a few. This was done by filling those divots with clear cyanoacrylate adhesive. I left this to cure and moved on.

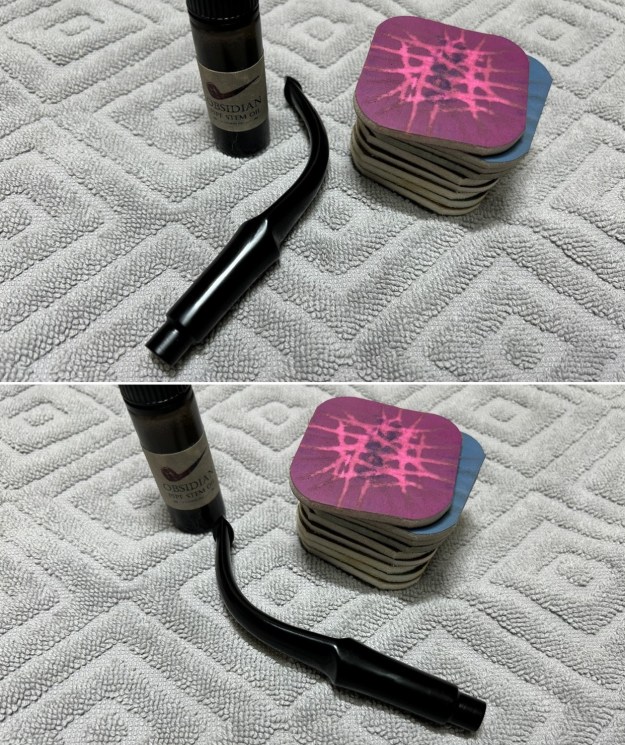

Since this stem was made of acrylic, there’s no oxidation and I can skip those steps and go right to repair. I set about fixing the marks and dents in the acrylic – of which there were quite a few. This was done by filling those divots with clear cyanoacrylate adhesive. I left this to cure and moved on. The penultimate step for the stem is sanding. First, with my set of needle files, I reduced the bulk of the cyanoacrylate repairs. I removed the excess adhesive as near to the surface as possible, without cutting into the acrylic. Following that, I used all nine of the micromesh sanding pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand out flaws, even out the acrylic, and provide gentle polishing of the finished surface. I also applied pipe-stem oil while using the last five micromesh pads. There was a wonderful shine on the stem when I was done.

The penultimate step for the stem is sanding. First, with my set of needle files, I reduced the bulk of the cyanoacrylate repairs. I removed the excess adhesive as near to the surface as possible, without cutting into the acrylic. Following that, I used all nine of the micromesh sanding pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand out flaws, even out the acrylic, and provide gentle polishing of the finished surface. I also applied pipe-stem oil while using the last five micromesh pads. There was a wonderful shine on the stem when I was done. As the stem was (nearly) complete, I moved on to the stummel. The first step was to ream out the bowl – that is to say, remove all the cake inside the bowl. This accomplished a couple of things. First (and most obviously), it cleaned the bowl and provided a refurbished chamber for future smoking. Second, when the old cake was removed, I could inspect the interior walls of the bowl and determine if there was damage or not. This pipe was quite clean and needed very little reaming. I used a pipe knife and a piece of sandpaper taped to a wooden dowel. Collectively, these ensured that all the debris was removed.

As the stem was (nearly) complete, I moved on to the stummel. The first step was to ream out the bowl – that is to say, remove all the cake inside the bowl. This accomplished a couple of things. First (and most obviously), it cleaned the bowl and provided a refurbished chamber for future smoking. Second, when the old cake was removed, I could inspect the interior walls of the bowl and determine if there was damage or not. This pipe was quite clean and needed very little reaming. I used a pipe knife and a piece of sandpaper taped to a wooden dowel. Collectively, these ensured that all the debris was removed. My next step was to remove the lava on the rim. For this, I took a piece of machine steel and gently scraped the lava away. The metal’s edge is sharp enough to remove what I need, but not so sharp that it damages the rim.

My next step was to remove the lava on the rim. For this, I took a piece of machine steel and gently scraped the lava away. The metal’s edge is sharp enough to remove what I need, but not so sharp that it damages the rim.

Similar to the stem, I then cleaned the stummel with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. I then decided to ‘de-ghost’ the pipe – that is to say, exorcize the remaining filth from the briar. I filled the bowl and the shank with cotton balls, then saturated them with 99% isopropyl alcohol. I let the stummel sit overnight. This caused the remaining oils, tars and smells to leach out into the cotton.

I then decided to ‘de-ghost’ the pipe – that is to say, exorcize the remaining filth from the briar. I filled the bowl and the shank with cotton balls, then saturated them with 99% isopropyl alcohol. I let the stummel sit overnight. This caused the remaining oils, tars and smells to leach out into the cotton. To tidy up the briar, I wiped down the outside, using a solution of a pH-neutral detergent and some distilled water, with cotton rounds. I also used a toothbrush in the crevices. This did a good job of cleaning any latent dirt on the surface of the briar. The last step of the cleaning process was to scour the inside of the stummel with the same mild detergent and tube brushes. This was the culmination of a lot of hard work in getting the pipe clean.

To tidy up the briar, I wiped down the outside, using a solution of a pH-neutral detergent and some distilled water, with cotton rounds. I also used a toothbrush in the crevices. This did a good job of cleaning any latent dirt on the surface of the briar. The last step of the cleaning process was to scour the inside of the stummel with the same mild detergent and tube brushes. This was the culmination of a lot of hard work in getting the pipe clean. I used all nine micromesh pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand only the smooth (non-rusticated) parts of the stummel and finish it off. This sanding minimizes flaws in the briar and provides a beautiful smoothness to the wood. I rubbed some LBE Before & After Restoration Balm into the briar and let it sit for 30 minutes or so. The balm moisturizes the wood and gives a beautiful depth to the briar. I then buffed the stummel with a microfibre cloth.

I used all nine micromesh pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand only the smooth (non-rusticated) parts of the stummel and finish it off. This sanding minimizes flaws in the briar and provides a beautiful smoothness to the wood. I rubbed some LBE Before & After Restoration Balm into the briar and let it sit for 30 minutes or so. The balm moisturizes the wood and gives a beautiful depth to the briar. I then buffed the stummel with a microfibre cloth.

For the final step, I took the pipe to my bench polisher and carefully buffed it with three coats of conservator’s wax. This procedure makes the pipe look its best – the stummel sings and the stem glows.

For the final step, I took the pipe to my bench polisher and carefully buffed it with three coats of conservator’s wax. This procedure makes the pipe look its best – the stummel sings and the stem glows.

All done! This Edward’s 20 Algerian Briar Bulldog looks fantastic again and is ready to be enjoyed by its next owner. I am pleased to announce that this pipe is for sale! If you are interested in acquiring it for your collection, please have a look in the ‘American’ section of the store here on Steve’s website. You can also email me directly at kenneth@knightsofthepipe.com. The approximate dimensions of the pipe are as follows: length 5⅞ in. (148 mm); height 1½ in. (38 mm); bowl diameter 1⅔ in. (42 mm); chamber diameter ⅞ in. (23 mm). The weight of the pipe is 1⅛ oz. (34 g). I hope you enjoyed reading the story of this pipe’s restoration as much as I enjoyed restoring it. If you are interested in more of my work, please follow me here on Steve’s website or send me an email. Thank you very much for reading and, as always, I welcome and encourage your comments.