by Kenneth Lieblich

Well, now, this is quite the pipe! I recently acquired a collection from a (late) gentleman who clearly LOVED his pipes. They were all well used and, according to his family, he had a pipe hanging out of his mouth at all times. As I was looking through them, this particular Pete caught my eye. It’s a handsome one, isn’t it? It’s a Peterson Kapruf 56 chubby bent billiard, with a beautiful sandblast. This one is really worth restoring. It’s such a comely pipe and deserves to be back in someone’s collection.

Let’s look at the markings. We’ve got Peterson’s [over] Kapruf. Then we have Made in the [over] Republic [over] of Ireland. Finally, there is the shape number, 56. Of course, there is also the stylized P on the stem, indicating the famous Peterson company of Ireland.

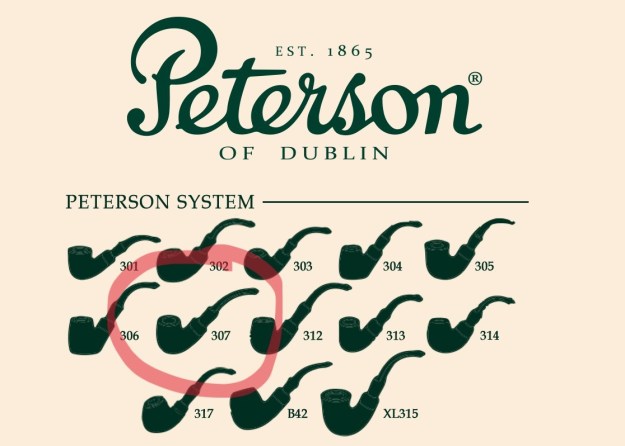

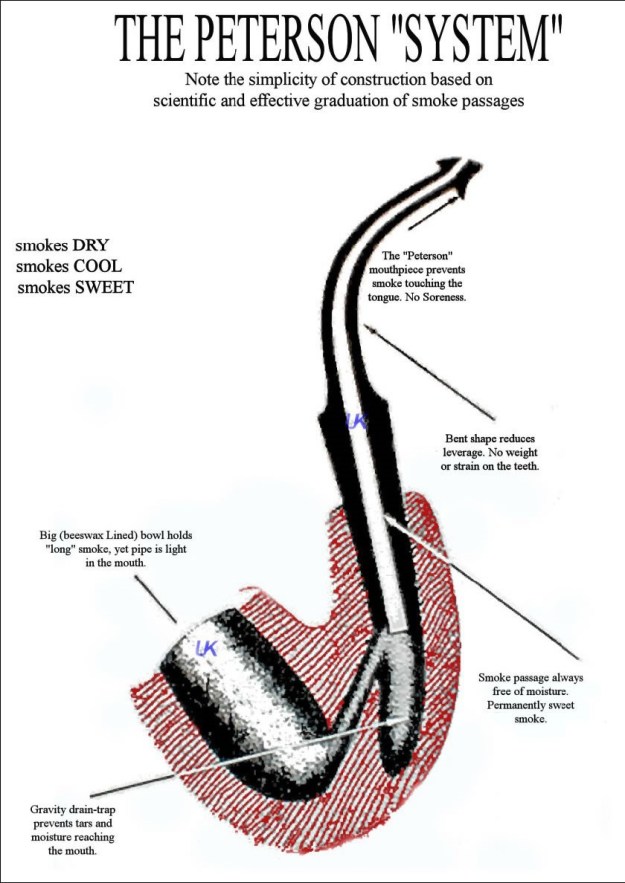

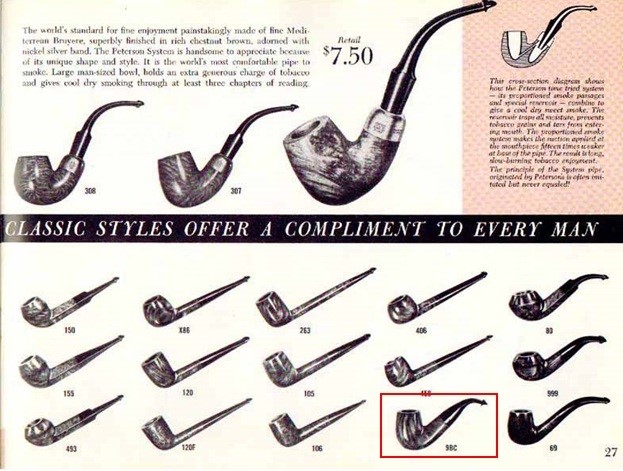

Let’s look at the markings. We’ve got Peterson’s [over] Kapruf. Then we have Made in the [over] Republic [over] of Ireland. Finally, there is the shape number, 56. Of course, there is also the stylized P on the stem, indicating the famous Peterson company of Ireland. The history and origins of this particular model are quite interesting. It’s an uncommon pipe and, if you’re a Pete collector, you ought to have one. In a blog post from 2019, Al Jones posted here on Reborn Pipes about a Kapruf 56 he had been working on and expounded on the background of this pipe. Rather than simply retyping what he wrote, I urge you to read his blog here and learn more. Meanwhile, here’s a catalogue photo from one of Steve’s blogs on the same pipe:

The history and origins of this particular model are quite interesting. It’s an uncommon pipe and, if you’re a Pete collector, you ought to have one. In a blog post from 2019, Al Jones posted here on Reborn Pipes about a Kapruf 56 he had been working on and expounded on the background of this pipe. Rather than simply retyping what he wrote, I urge you to read his blog here and learn more. Meanwhile, here’s a catalogue photo from one of Steve’s blogs on the same pipe: I’m not going to sugarcoat this for you: the pipe was a bit of a mess. The stummel was in decent condition, but so, so dirty and clogged. The stem, on the other hand, was a localized disaster. The oxidation was extreme, the chomping of the bit was extreme, the tooth scrapings were extreme – and there was a small fissure in the vulcanite (on the underside of the P-lip to boot. I had my work cut out for me.

I’m not going to sugarcoat this for you: the pipe was a bit of a mess. The stummel was in decent condition, but so, so dirty and clogged. The stem, on the other hand, was a localized disaster. The oxidation was extreme, the chomping of the bit was extreme, the tooth scrapings were extreme – and there was a small fissure in the vulcanite (on the underside of the P-lip to boot. I had my work cut out for me.

I used a disposable lighter and ‘painted’ the stem with its flame. The gentle heat of the flame can cause the dents in the vulcanite of the stem to expand back into shape. Sadly, in this case, not much happened. The stem’s calcification was quite substantial. I used an old butter knife and gently scraped some of the thicker accretion off. Doing this now helps later in removing the oxidation.

I used a disposable lighter and ‘painted’ the stem with its flame. The gentle heat of the flame can cause the dents in the vulcanite of the stem to expand back into shape. Sadly, in this case, not much happened. The stem’s calcification was quite substantial. I used an old butter knife and gently scraped some of the thicker accretion off. Doing this now helps later in removing the oxidation.

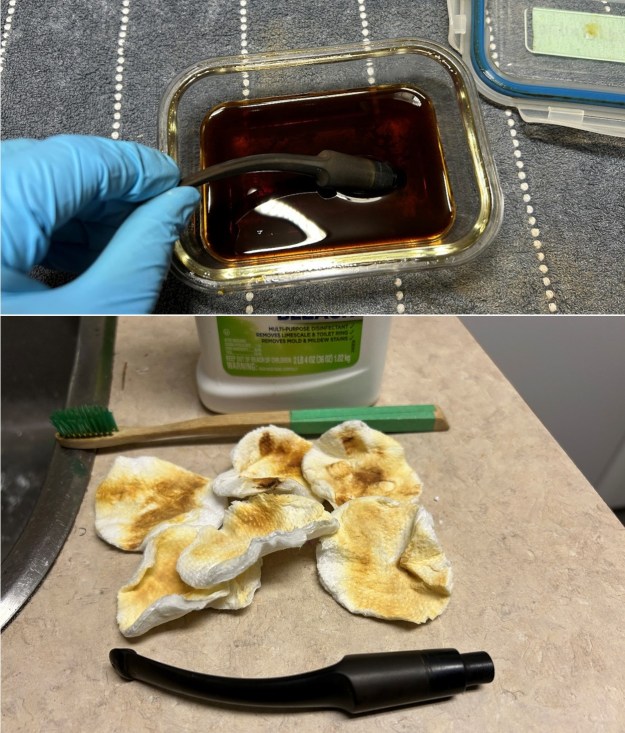

I used isopropyl alcohol on a few cotton rounds and wiped down the stem to provide an initial cleaning of filth before moving on to the next steps. The primary cleaning came next. I disinfected the inside of the stem with pipe cleaners dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. I scrubbed thoroughly to make sure the interior was very clean. Given the general state of the pipe, I was surprised at how relatively clean it was. The goal of the next step is the removal (or minimization) of oxidation. Going to my sink, I used cream cleanser, cotton rounds, and a toothbrush, and scoured the stem to remove as much surface oxidation as possible. As the photos show, the result was a hideous, brownish mess – but better off the stem than on it.

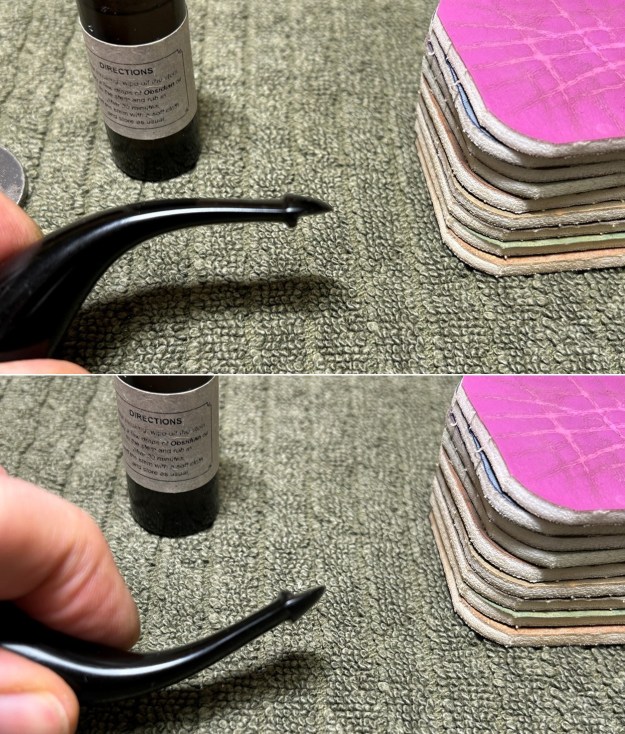

The goal of the next step is the removal (or minimization) of oxidation. Going to my sink, I used cream cleanser, cotton rounds, and a toothbrush, and scoured the stem to remove as much surface oxidation as possible. As the photos show, the result was a hideous, brownish mess – but better off the stem than on it. Once the stem was reasonably clean, I soaked it overnight in some Briarville Stem Oxidation Remover. This solution works to draw oxidation in the stem to the surface of the vulcanite. This is a major aid and an important step in ensuring a clean stem. The following day, I drew out the stem from its bath and scrubbed the lingering fluid with a toothbrush. Due to the severity of the oxidation, I then repeated the scrubbing with the cream cleanser for maximum effect.

Once the stem was reasonably clean, I soaked it overnight in some Briarville Stem Oxidation Remover. This solution works to draw oxidation in the stem to the surface of the vulcanite. This is a major aid and an important step in ensuring a clean stem. The following day, I drew out the stem from its bath and scrubbed the lingering fluid with a toothbrush. Due to the severity of the oxidation, I then repeated the scrubbing with the cream cleanser for maximum effect. As the stem was now clean and dry, I set about fixing the marks and dents in the vulcanite. Quite frankly, this was a substantial rebuild of the button – including the fissure on the underside. This was done by filling those parts with black cyanoacrylate adhesive, impregnated with carbon and rubber. I left this to cure and moved on.

As the stem was now clean and dry, I set about fixing the marks and dents in the vulcanite. Quite frankly, this was a substantial rebuild of the button – including the fissure on the underside. This was done by filling those parts with black cyanoacrylate adhesive, impregnated with carbon and rubber. I left this to cure and moved on.

After this, I painted the logo on the stem with some enamel nail polish. I restored the logo carefully and let it fully set before proceeding.

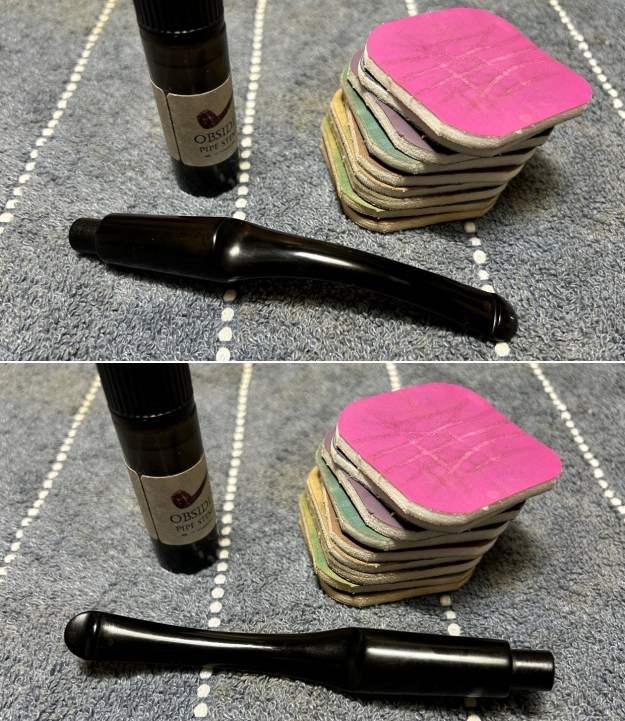

After this, I painted the logo on the stem with some enamel nail polish. I restored the logo carefully and let it fully set before proceeding. The penultimate step for the stem is sanding. First, with my set of needle files, I reduced the bulk of the cyanoacrylate repairs. I removed the excess adhesive as near to the surface as possible, without cutting into the vulcanite. Following that, I used all nine of the micromesh sanding pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand out flaws, even out the vulcanite, and provide gentle polishing of the finished surface. I also applied pipe-stem oil while using the last five micromesh pads. There was a wonderful, deep black shine to the stem when I was done. You can see in the profile photo below just how much better the P-lip looks after my work.

The penultimate step for the stem is sanding. First, with my set of needle files, I reduced the bulk of the cyanoacrylate repairs. I removed the excess adhesive as near to the surface as possible, without cutting into the vulcanite. Following that, I used all nine of the micromesh sanding pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand out flaws, even out the vulcanite, and provide gentle polishing of the finished surface. I also applied pipe-stem oil while using the last five micromesh pads. There was a wonderful, deep black shine to the stem when I was done. You can see in the profile photo below just how much better the P-lip looks after my work.

As the stem was (nearly) complete, I moved on to the stummel. The first step was to ream out the bowl – that is to say, remove all the cake inside the bowl. This accomplished a couple of things. First (and most obviously), it cleaned the bowl and provided a refurbished chamber for future smoking. Second, when the old cake was removed, I could inspect the interior walls of the bowl and determine if there was damage or not. I used a reamer, a pipe knife, and a piece of sandpaper taped to a wooden dowel. Collectively, these ensured that all the debris was removed.

As the stem was (nearly) complete, I moved on to the stummel. The first step was to ream out the bowl – that is to say, remove all the cake inside the bowl. This accomplished a couple of things. First (and most obviously), it cleaned the bowl and provided a refurbished chamber for future smoking. Second, when the old cake was removed, I could inspect the interior walls of the bowl and determine if there was damage or not. I used a reamer, a pipe knife, and a piece of sandpaper taped to a wooden dowel. Collectively, these ensured that all the debris was removed. The inside of the stummel needed to be cleaned thoroughly. However, this pipe was so clogged, that I first needed to open the horribly occluded airway. So, I took a long drill bit, held in a drill chuck, and hand-cranked it to dislodge the dreadful detritus inside. Hand cranking is essential because it provides a precision and caution that a power drill cannot provide. Similar to the stem, I then cleaned the stummel with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. With a pipe this dirty, it took quite a while and much cotton to get clean.

The inside of the stummel needed to be cleaned thoroughly. However, this pipe was so clogged, that I first needed to open the horribly occluded airway. So, I took a long drill bit, held in a drill chuck, and hand-cranked it to dislodge the dreadful detritus inside. Hand cranking is essential because it provides a precision and caution that a power drill cannot provide. Similar to the stem, I then cleaned the stummel with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. With a pipe this dirty, it took quite a while and much cotton to get clean. I then decided to ‘de-ghost’ the pipe – that is to say, exorcize the remaining filth from the briar. I filled the bowl and the shank with cotton balls, then saturated them with 99% isopropyl alcohol. I let the stummel sit overnight. This caused the remaining oils, tars and smells to leach out into the cotton.

I then decided to ‘de-ghost’ the pipe – that is to say, exorcize the remaining filth from the briar. I filled the bowl and the shank with cotton balls, then saturated them with 99% isopropyl alcohol. I let the stummel sit overnight. This caused the remaining oils, tars and smells to leach out into the cotton. To tidy up the briar, I wiped down the outside, using a solution of a pH-neutral detergent and distilled water, with cotton rounds. I also used a toothbrush in the crevices. I also scoured the inside of the stummel with the same detergent and tube brushes. This was the culmination of a lot of hard work in getting the pipe clean.

To tidy up the briar, I wiped down the outside, using a solution of a pH-neutral detergent and distilled water, with cotton rounds. I also used a toothbrush in the crevices. I also scoured the inside of the stummel with the same detergent and tube brushes. This was the culmination of a lot of hard work in getting the pipe clean. I rubbed some LBE Before & After Restoration Balm into the briar and let it sit for 30 minutes or so. The balm moisturizes the wood and gives a beautiful depth to the briar. I then buffed the stummel with a microfibre cloth.

I rubbed some LBE Before & After Restoration Balm into the briar and let it sit for 30 minutes or so. The balm moisturizes the wood and gives a beautiful depth to the briar. I then buffed the stummel with a microfibre cloth.

For the final step, I took the pipe to my bench polisher and carefully buffed it – with three coats of conservator’s wax. This procedure makes the pipe look its best – the stummel sings and the stem glows.

For the final step, I took the pipe to my bench polisher and carefully buffed it – with three coats of conservator’s wax. This procedure makes the pipe look its best – the stummel sings and the stem glows.

This Peterson Kapruf 56 looks fantastic again and is ready to be enjoyed by its next owner. I am pleased to announce that this pipe is for sale! If you are interested in acquiring it for your collection, please have a look in the ‘Irish’ pipe section of the store here on Steve’s website. You can also email me directly at kenneth@knightsofthepipe.com. The approximate dimensions of the pipe are as follows: length 5½ in. (140 mm); height 2 in. (52 mm); bowl diameter 1½ in. (38 mm); chamber diameter ¾ in. (20 mm). The weight of the pipe is 1⅞ oz. (55 g). I hope you enjoyed reading the story of this pipe’s restoration as much as I did restoring it. If you are interested in more of my work, please follow me here on Steve’s website or send me an email. Thank you very much for reading and, as always, I welcome and encourage your comments.