Blog by Steve Laug

I thought I would continue with the same tack I took on the three pipes and take you through my process of working on each pipe that we purchase. Jeff has set up a spread sheet to track where the pipe came from, the date of purchase and what we paid for it so that we know what we have invested in the pipe before we even work on it. This takes a lot of the guess work out of the process. This particular pipe was purchased on 01/26/2023 in a group of pipes from a fellow in Copenhagen, Denmark. I also want you to understand why we take the photos we do. It is not accidental or chance as the photos have been taken to help me make an assessment of the pipe Jeff sees before he starts his clean up work. We do this to record the condition that the pipe was in when received it and to assess what kind of work will need to be done on. When I look at these photos this is what I see.

- The finish is dirty with dust grooves and valleys of the sandblast bowl and shank. There are some tars and lava flowing down the edges of the rim cap. Underneath there appears to be some excellent grain.

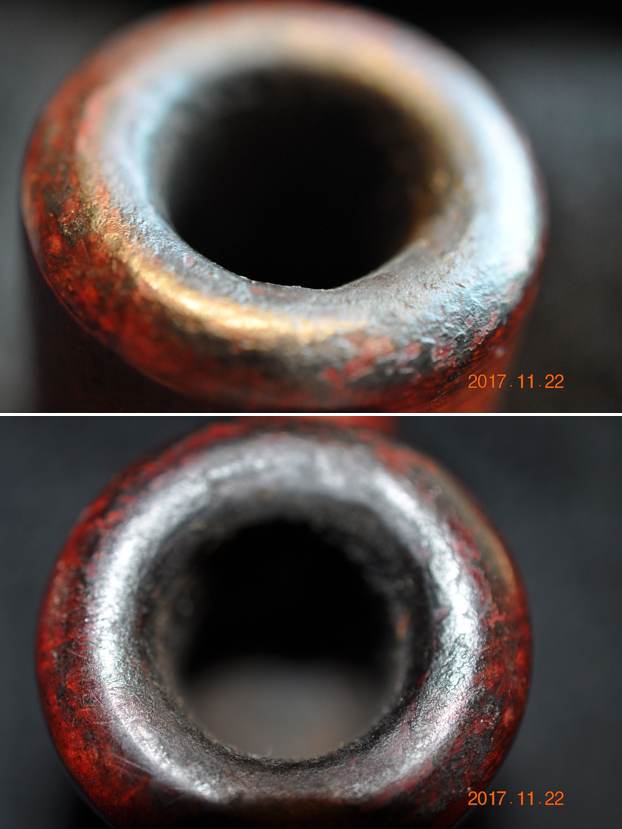

- The sandblast rim top is dirty. There is some lava overflow from the cake in the bowl and some darkening on the rim top.

- The bowl has a thick cake in it but the inner and outer edge of the bowl actually look to be undamaged from what I can see at this point. There does not appear to be any burning or reaming damage to the edges of the bowl.

- The stem is vulcanite and has the Parker P logo in Diamond stamped into the top of the thin oval stem. The stamp is devoid of colour but it still readable.

- The vulcanite stem has some light oxidation but was dirty. There were tooth marks and chatter ahead of the button that are visible in the photos below. Nothing to deep but nonetheless present.

Overall my impressions of this dainty Parker Super Bark Canadian was that it was in solid shape with no significant damage to the briar on the bowl sides and rim. The cake does not seem to hide any burns or checking but I will know more once it is cleaned and reamed. The exterior of the bowl does not show any hot spots or darkening. The photos below confirm the assessment above.

Jeff always takes close up photos of key areas on the pipe we buy. These are done so that I can have a clearer picture of the condition of the bowl and rim edges and top. The rim top photos confirm my assessment above. The cake in the bowl is quite thick and the rim top has heavy lava and debris on it that will need to come off. You can also see the lava in the sandblast finish on the rim. You can also see the condition of the inner and outer edges of the rim. This is what I look for when assessing a pipe. While there is lava and darkening there is no visible burn damage at this point and the previous reamings has not left damage either. The bowl is still round.

Jeff always takes close up photos of key areas on the pipe we buy. These are done so that I can have a clearer picture of the condition of the bowl and rim edges and top. The rim top photos confirm my assessment above. The cake in the bowl is quite thick and the rim top has heavy lava and debris on it that will need to come off. You can also see the lava in the sandblast finish on the rim. You can also see the condition of the inner and outer edges of the rim. This is what I look for when assessing a pipe. While there is lava and darkening there is no visible burn damage at this point and the previous reamings has not left damage either. The bowl is still round.

His photos of the stem surface confirmed and heightened my assessment of the condition. You can see the oxidation on the stem surface. You can see the faded out stamp on the top of the stem. Note also the tooth marks on the stem surface ahead of the button on both sides.

His photos of the stem surface confirmed and heightened my assessment of the condition. You can see the oxidation on the stem surface. You can see the faded out stamp on the top of the stem. Note also the tooth marks on the stem surface ahead of the button on both sides.

I always ask Jeff to take photos of the sides and heel of the bowl. While this definitely shows the sandblast patterns around the bowl it also allows me to do a more thorough assessment of the condition of the briar and the finish. The stain on the bowl highlights the grain. There was some grime on the surface but the cleaning will easily remove that. There were no cracks or splits following the grain or coming down from the rim edges. There were no cracks in the shank. I also look for flaws in the grain as those can also hide cracks or damage. In this case the bowl exterior is sound and should clean up very well. I love the sandblast patterns that appear to have a mix of grain underneath it.

I always ask Jeff to take photos of the sides and heel of the bowl. While this definitely shows the sandblast patterns around the bowl it also allows me to do a more thorough assessment of the condition of the briar and the finish. The stain on the bowl highlights the grain. There was some grime on the surface but the cleaning will easily remove that. There were no cracks or splits following the grain or coming down from the rim edges. There were no cracks in the shank. I also look for flaws in the grain as those can also hide cracks or damage. In this case the bowl exterior is sound and should clean up very well. I love the sandblast patterns that appear to have a mix of grain underneath it.

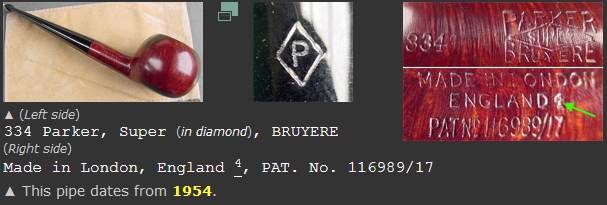

I also ask him to take photos of the stamping so I can see if it is faint in any spots or double stamped or unclear. It often takes several photos to capture what I am looking for. The stamping on the underside of the shank are clear and readable in the pictures below. There is some faint spots in the stamp but it can still be read. On the heel of the bowl the stamping reads Parker [over] Super in a flattened diamond [over] Briar Bark. The stamping wraps over and under the diamond stamp. That followed by Made In London [over] England followed by the number 3 in a circle which is the size of the pipe according to Dunhill’s size numbers making it a Group 3 size. The last stamp on the shank near the shank/stem joint it bears the shape number 132 which is the shape number for a Canadian. Jeff also included a photo of the stamped stem logo – Parker “P” in a Diamond.

I also ask him to take photos of the stamping so I can see if it is faint in any spots or double stamped or unclear. It often takes several photos to capture what I am looking for. The stamping on the underside of the shank are clear and readable in the pictures below. There is some faint spots in the stamp but it can still be read. On the heel of the bowl the stamping reads Parker [over] Super in a flattened diamond [over] Briar Bark. The stamping wraps over and under the diamond stamp. That followed by Made In London [over] England followed by the number 3 in a circle which is the size of the pipe according to Dunhill’s size numbers making it a Group 3 size. The last stamp on the shank near the shank/stem joint it bears the shape number 132 which is the shape number for a Canadian. Jeff also included a photo of the stamped stem logo – Parker “P” in a Diamond.

I did not take time to do work on the brand as it is a well known brand. There is no date stamp on the shank so I cannot link it to any specific time period. If you would like to do some reading on it you can check both Pipephil’s site and Pipedia for a great write up on the history of the brand. I decided instead to just get to work on the pipe.

I did not take time to do work on the brand as it is a well known brand. There is no date stamp on the shank so I cannot link it to any specific time period. If you would like to do some reading on it you can check both Pipephil’s site and Pipedia for a great write up on the history of the brand. I decided instead to just get to work on the pipe.

I am sure many of you skip my paragraph on the work Jeff has done before the pipe gets here in my many blogs but it is quite detailed in its brevity. I know some laugh at my opening line Jeff did a thorough cleaning of this pipe. However, I want you to know the details of the work. Back in 2020 Jeff wrote a blog about his cleaning process. I am including a link to that now so you can see what I mean about his process. Do not skip it! Give it a read (https://rebornpipes.com/2020/01/20/got-a-filthy-estate-pipe-that-you-need-to-clean/). Here is the introduction to that blog and it is very true even to this day.

Several have asked about Jeff’s cleaning regimen as I generally summarize it in the blogs that I post rather than give a detailed procedure. I have had the question asked enough that I asked Jeff to put together this blog so that you can get a clear picture of the process he uses. Like everything else in our hobby, people have different methods they swear by. Some may question the method and that is fine. But it works very well for us and has for many years. Some of his steps may surprise you but I know that when I get the pipes from him for my part of the restoration they are impeccably clean and sanitized. I have come to appreciate the thoroughness of the process he has developed because I really like working on clean pipe!

For the benefit of some of you who may be unfamiliar with some of the products he uses I have included photos of three of the items that Jeff mentions in his list. This will make it easier for recognition. These three are definitely North American Products so you will need to find suitable replacements or order these directly on Amazon. The makeup pads are fairly universal as we were able to pick some up in India when we were with Paresh and his family.

In the blog itself he breaks his process down into two parts – cleaning the stem and cleaning the bowl. Each one has a large number of steps that he methodically does every time. I know because I have watched him do the work and I have seen the pipes after his work on them. He followed this process step by step and when the pipe got to me it was spotlessly clean and ready for my work. The inside of the stem, shank and bowl were clean and to me that is an amazing gift as it means that my work on this end is with a clean pipe! I cannot tell you how much difference that makes for my work.

When the pipe arrives here in Vancouver I have a clean pipe and I go over it keeping in mind my assessment shared in the opening paragraph above. I am looking for any significant structural changes in the bowl and finish as I go over it.

- The finish cleaned up really well and the dust and grime in the sandblast grooves and crevices was gone. It was very clean and was undamaged. The rim top and the beveled inner edge looked very good. With all the grime removed there was some excellent grain coming through the blast.

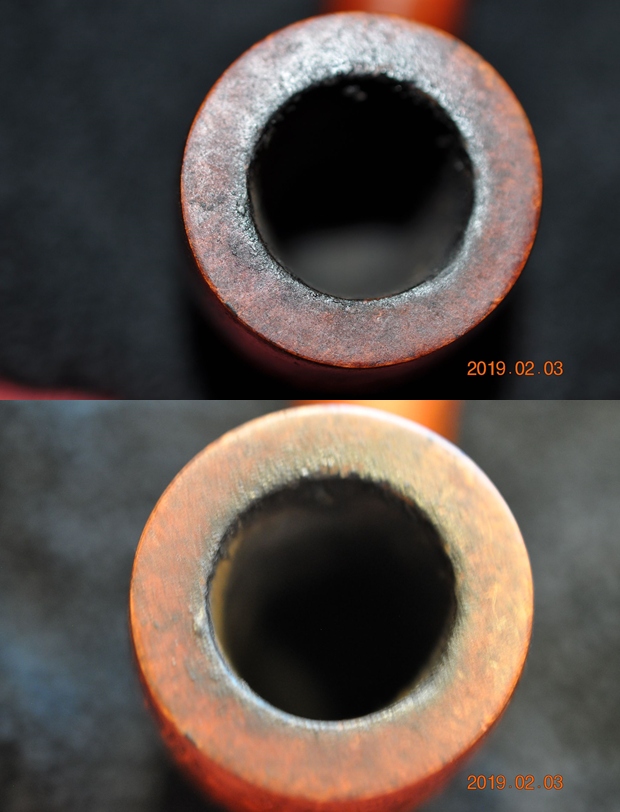

- The sandblast rim top cleaned up very well, though was still some darkening on the briar. It looked to be in decent condition.

- The bowl was very clean and the top and inner edge of the bowl show no damage. The bowl walls are also very clean and smooth with no checking or burn marks on the inside or out of the bowl. The walls were undamaged.

- The vulcanite taper stem with the Parker “P” Diamond logo stamped into the topside looks good but there is nothing remaining in the stamp. It appears to be deep enough to reapply the colour to the top.

- The vulcanite stems still showed some oxidation that would need to be addressed. There were light tooth marks and chatter ahead of the button that are barely visible in the photos below. Nothing to deep but nonetheless present.

Hopefully the steps above show you both what I look for when I go over the pipe when I bring it to the work table and also what I see when I look at the pipe in my hands. They also clearly spell out a restoration plan in short form. My work is clear and addressing it will be the next steps. I took photos of the whole pipe to give you a picture of what I see when I have it on the table. This is important to me in that it also shows that there was no damage done during the clean up work or the transit of the pipe from Idaho to here in Vancouver.

I then spent some time going over the bowl and rim top to get a sense of what is happening there. The bowl looked very good and the walls were smooth. There was no damage internally. The rim top was clean but there seemed to be some darkening still remaining in the grooves. I also went over the stem carefully. There were dents in the stem that are visible in the photos. But the good news is that the tooth marks were not deep and did not seem to puncture the airway. They would clean up well. I examined the button edge and was happy to see that the marks there were not too bad and should be able to be sanded out. I took photos of the rim top and stem sides to show as best as I can what I see when I look at them.

I then spent some time going over the bowl and rim top to get a sense of what is happening there. The bowl looked very good and the walls were smooth. There was no damage internally. The rim top was clean but there seemed to be some darkening still remaining in the grooves. I also went over the stem carefully. There were dents in the stem that are visible in the photos. But the good news is that the tooth marks were not deep and did not seem to puncture the airway. They would clean up well. I examined the button edge and was happy to see that the marks there were not too bad and should be able to be sanded out. I took photos of the rim top and stem sides to show as best as I can what I see when I look at them. I always check to make sure that the clean up work did not damage the stamping on the shank in any way. I know Jeff is cognizant of this but I do it anyway and take a photo to show what I see when I examine it. In this case it has not changed at all from the pictures I included above. I took a photo of the Diamond P stamp on the stem as well. You can see it is deep enough to hold some colour once I repair it. I removed the stem from the shank and checked the tenon and lay the parts of the pipe out to get a sense of the proportion that was in the mind of the pipe maker when he crafted the pipe. It is a beauty in flow and shape.

I always check to make sure that the clean up work did not damage the stamping on the shank in any way. I know Jeff is cognizant of this but I do it anyway and take a photo to show what I see when I examine it. In this case it has not changed at all from the pictures I included above. I took a photo of the Diamond P stamp on the stem as well. You can see it is deep enough to hold some colour once I repair it. I removed the stem from the shank and checked the tenon and lay the parts of the pipe out to get a sense of the proportion that was in the mind of the pipe maker when he crafted the pipe. It is a beauty in flow and shape. As I pointed out in a previous blog, the question of where to begin the restoration work is always a matter of personal preference. If you read this blog much you will see that each of the restorers who post here all start at different points. Kenneth always starts with the stems, others as well do that. I personally like to start with the bowl because it gives me hope that this pipe is really a beauty. I said previously that I truly do not like the tedious work of stem repairs and stem polishing. I have been thinking about that and I think it is more it takes longer for slower results. I think that is why I always leave that until last even though I know that it needs to be done. So if you are restoring your pipes choose where you want to start and go from there. Just know that it all will need to be done by the end but for me the encouragement of seeing a rejuvenated bowl is the impetus I need to attack the stem work.

As I pointed out in a previous blog, the question of where to begin the restoration work is always a matter of personal preference. If you read this blog much you will see that each of the restorers who post here all start at different points. Kenneth always starts with the stems, others as well do that. I personally like to start with the bowl because it gives me hope that this pipe is really a beauty. I said previously that I truly do not like the tedious work of stem repairs and stem polishing. I have been thinking about that and I think it is more it takes longer for slower results. I think that is why I always leave that until last even though I know that it needs to be done. So if you are restoring your pipes choose where you want to start and go from there. Just know that it all will need to be done by the end but for me the encouragement of seeing a rejuvenated bowl is the impetus I need to attack the stem work.

Knowing that about me you can guess that I started working on this pipe by turning to the bowl. The bowl was in great condition over all with a bit of darkening still in the sandblast on the rim top. I decided to clean up the rim top. I use a brass bristle wire brush to work it over and clean up the remaining debris in the sandblast.  The bowl was ready for the next stem in the process. I use a product developed by Mark Hoover called Before & After Restoration Balm. It is a paste/balm that is rubbed into the surface of the briar. The product works to deep clean the finish, enliven and protect the briar. I worked it into the briar with my finger tips and a shoe brush to make sure that it covers every square inch of the pipe. I set it aside for 10 minutes to let it do its work. Once the time has passed I wiped it off with a soft cloth then buffed it with a cotton cloth. The briar really began to have a deep shine and show some contrast in the sandblast finish. The photos I took of the bowl at this point mark the progress in the restoration. You see the shine that the briar has taken on and the way the grain just pops. It is a gorgeous pipe.

The bowl was ready for the next stem in the process. I use a product developed by Mark Hoover called Before & After Restoration Balm. It is a paste/balm that is rubbed into the surface of the briar. The product works to deep clean the finish, enliven and protect the briar. I worked it into the briar with my finger tips and a shoe brush to make sure that it covers every square inch of the pipe. I set it aside for 10 minutes to let it do its work. Once the time has passed I wiped it off with a soft cloth then buffed it with a cotton cloth. The briar really began to have a deep shine and show some contrast in the sandblast finish. The photos I took of the bowl at this point mark the progress in the restoration. You see the shine that the briar has taken on and the way the grain just pops. It is a gorgeous pipe.

Now it was time to address the part of the restoration I leave until last. I set the bowl aside and turned my attention to the stem. The stem was in quite good shape. Jeff had been able to remove much of the oxidation so that when it came it looked pretty good. I needed to deal with the remaining oxidation and to address the tooth marks at the same time. I sanded the stem surface with 220 grit sandpaper and start polishing it with 600 grit wet dry sandpaper to remove the oxidation. This process removes the oxidation and the marks. Here are photos of the stem after the sandpaper work.

Now it was time to address the part of the restoration I leave until last. I set the bowl aside and turned my attention to the stem. The stem was in quite good shape. Jeff had been able to remove much of the oxidation so that when it came it looked pretty good. I needed to deal with the remaining oxidation and to address the tooth marks at the same time. I sanded the stem surface with 220 grit sandpaper and start polishing it with 600 grit wet dry sandpaper to remove the oxidation. This process removes the oxidation and the marks. Here are photos of the stem after the sandpaper work. I then took some time to touch up the Diamond “P” Parker logo on the topside of the stem with white acrylic fingernail polish. I worked it into the stamp on the stem with a tooth pick to ensure that it went deep into the stamp. Once it cured I scraped off the excess and the stamp looked very good.

I then took some time to touch up the Diamond “P” Parker logo on the topside of the stem with white acrylic fingernail polish. I worked it into the stamp on the stem with a tooth pick to ensure that it went deep into the stamp. Once it cured I scraped off the excess and the stamp looked very good.  It was the time now to polish the stem and remove the scratching and bring back a shine. Over the years I have developed my own process for this. It is all preparation for the buffing that will come last. I use micromesh sanding pads and water to wet sand the stem with 1500-12000 grit sanding pads. I wiped it down after each sanding pad with Obsidian Oil on a cotton rag after each sanding pad as I find it does two things – first it protects the vulcanite and second it give the sanding pads bite in the polishing process.

It was the time now to polish the stem and remove the scratching and bring back a shine. Over the years I have developed my own process for this. It is all preparation for the buffing that will come last. I use micromesh sanding pads and water to wet sand the stem with 1500-12000 grit sanding pads. I wiped it down after each sanding pad with Obsidian Oil on a cotton rag after each sanding pad as I find it does two things – first it protects the vulcanite and second it give the sanding pads bite in the polishing process. After finishing with the micromesh pads I always rub the stem down with Before & After Fine and Extra Fine stem polish as it seems to really remove the fine scratches in the vulcanite. I rub the Fine Polish on the stem and wipe it off with a paper towel and then repeat the process with the Extra Fine polish. I finish the polishing of the stem by wiping it down with a final coat of Obsidian Oil and set the stem aside to let the oil absorb. This process gives the stem a shine and also a bit of protection from oxidizing quickly.

After finishing with the micromesh pads I always rub the stem down with Before & After Fine and Extra Fine stem polish as it seems to really remove the fine scratches in the vulcanite. I rub the Fine Polish on the stem and wipe it off with a paper towel and then repeat the process with the Extra Fine polish. I finish the polishing of the stem by wiping it down with a final coat of Obsidian Oil and set the stem aside to let the oil absorb. This process gives the stem a shine and also a bit of protection from oxidizing quickly. The final steps in my process involve using the buffer. I buff the stem and the briar with Blue Diamond on the buffing wheel. Blue Diamond is a plastic polish but I find that it works very well to polish out the light scratches in the vulcanite and the briar. I work the pipe over on the wheel with my finger or thumb in the bowl to keep it from becoming airborne. It works well and I am able to carefully move forward with the buffing. I lightly buff the plateau on the rim top and shank end at the same time making sure to keep the product from building up in the grooves of the finish.

The final steps in my process involve using the buffer. I buff the stem and the briar with Blue Diamond on the buffing wheel. Blue Diamond is a plastic polish but I find that it works very well to polish out the light scratches in the vulcanite and the briar. I work the pipe over on the wheel with my finger or thumb in the bowl to keep it from becoming airborne. It works well and I am able to carefully move forward with the buffing. I lightly buff the plateau on the rim top and shank end at the same time making sure to keep the product from building up in the grooves of the finish.

I finished with the Blue Diamond and moved on to buffing with carnauba wax. Once I have a good shine in the briar and vulcanite I always give the bowl and the stem multiple coats of carnauba wax. I have found that I can get a deeper shine if I following up the wax buff with a clean buffing pad. It works to raise the shine and then I follow that up with a hand buff with a microfiber cloth to deepen the shine. It is always fun for me to see what the polished bowl looks like with the polished vulcanite stem. It really is a beautiful pipe. The smooth finish around the bowl sides and shank show the grain shining through the rich brown stains of this Parker Super Bark Sandblast 132 Canadian and the polished vulcanite stem is a great addition. The finished pipe feels great in my hand. It is light and well balanced. Have a look at it with the photos below. The dimensions are Length: 5 ½ inches, Height: 1 ½ inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 1/8 inches, Chamber diameter: ¾ of an inch. The weight of the pipe is .92 ounces/25 grams. It is a beautiful pipe and one that I will be putting on the rebornpipes store in the British Pipe Maker section.

I finished with the Blue Diamond and moved on to buffing with carnauba wax. Once I have a good shine in the briar and vulcanite I always give the bowl and the stem multiple coats of carnauba wax. I have found that I can get a deeper shine if I following up the wax buff with a clean buffing pad. It works to raise the shine and then I follow that up with a hand buff with a microfiber cloth to deepen the shine. It is always fun for me to see what the polished bowl looks like with the polished vulcanite stem. It really is a beautiful pipe. The smooth finish around the bowl sides and shank show the grain shining through the rich brown stains of this Parker Super Bark Sandblast 132 Canadian and the polished vulcanite stem is a great addition. The finished pipe feels great in my hand. It is light and well balanced. Have a look at it with the photos below. The dimensions are Length: 5 ½ inches, Height: 1 ½ inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 1/8 inches, Chamber diameter: ¾ of an inch. The weight of the pipe is .92 ounces/25 grams. It is a beautiful pipe and one that I will be putting on the rebornpipes store in the British Pipe Maker section.

Hopefully this tack of writing this blog is helpful to you in some way. In it I show both what I am looking for and how I move forward in addressing what I see when work on a pipe has been helpful to you. It is probably the most straightforward detailed description of my work process. As always I encourage your questions and comments as you read the blog. Thanks to each of you who are reading this blog. Remember we are not pipe owners; we are pipemen and women who hold our pipes in trust until they pass on into the trust of those who follow us.