by Kenneth Lieblich

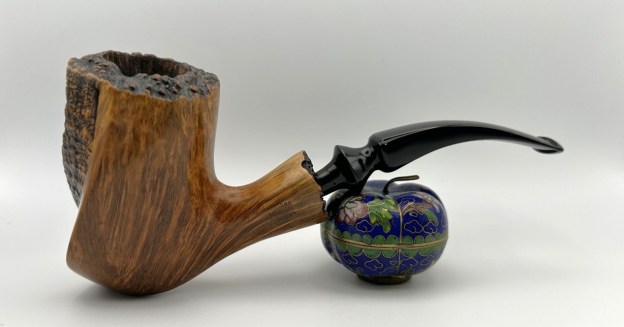

When I first saw this pipe, I thought that it was a very fine example of Danish pipemaking. But the more I worked on it, the more I recognized the incredible workmanship involved in carving it. This is a majestic, hand-finished freehand from master carver, Viggo Nielsen. This is the sort of pipe that offers you more each time you look at it. Examining the curves, angles, transitions, and plateau was very rewarding and reminded me of a rugged mountain landscape. It’s a beautiful pipe!

There are some markings on the shank of this pipe and they are helpful for identification. On the left side of the shank, we see Nielsen [over] Handmade [over] in Denmark. On the right side of the shank, we see Hand [over] Finished. That’s all – no other markings to be found.

There are some markings on the shank of this pipe and they are helpful for identification. On the left side of the shank, we see Nielsen [over] Handmade [over] in Denmark. On the right side of the shank, we see Hand [over] Finished. That’s all – no other markings to be found. It is worth looking up the work of Viggo Nielsen from the usual sources. On Pipedia, his article states:

It is worth looking up the work of Viggo Nielsen from the usual sources. On Pipedia, his article states:

Viggo is surely one of the seminal figures in the evolution of the Danish pipe. His pipes are all handmade – also handmade stems, often in Cumberland. Most of the pipes are quite big, and a large number are made for 9mm filter. The finish is just perfect and when holding one of Viggo’s pipes, you can tell, he’s a pro.

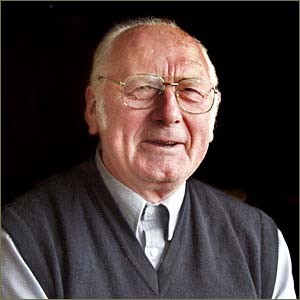

Viggo Nielsen was born in 1927. During World War II he started making pipes at a now closed factory. These pipes were made of birch due to the lack of briar (because of the war). In 1948 Viggo started his own pipe factory, “Bari”. But it wasn’t until 3 years later he could actually acquire Briar wood for his pipes. The business was very successful producing both classic shapes and freehand models.

In 1978 Viggo sold the business to a German tobacco manufacturer and he began making the Fåborg Pipe together with his two sons Jørgen Nielsen and Kai Nielsen. Even when Viggo had reached the age of retirement, he could not quite leave his workshop and he still made about 100 pipes a year, some of them based on the famous “Fåborg Pibe” but also a few “Jewels of Denmark”, until he passed away.

This pipe doesn’t have a Cumberland stem, nor a filter, but it is a healthy size. I also went to Pipephil and found the following:

Artisan: Viggo Nielsen (1927 – †2009) starts making pipes during WWII. He estabishes his own Bari factory in 1948. The business is sold to a German tobacco manufacturer in 1978 and from this period on he starts the “Faaborg Pipe” (Fåborg Pibe) with his two sons Jørgen Nielsen and Kai Nielsen. The “Jewel of Denmark” stamping is reserved for perfect pipes (flawless straight grain).

Let’s examine this wonderful specimen. The pipe was in great condition – just very dirty from lots of smoking. You can see lots of lava on the plateau rim top. The briar bowl was in nice shape, with a bit of grime ground in. The stem was well-worn, but a good, solid freehand stem. It has a few tooth marks and some oxidation, but nothing to worry about.

To begin, I used isopropyl alcohol on a few cotton rounds and wiped down the stem to provide an initial cleaning of filth before moving on to the next steps. The primary cleaning came next. I disinfected the inside of the stem with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. I scrubbed thoroughly to make sure the interior was very clean. I used quite a few pipe cleaners and cotton swabs – far more than are shown in the photo.

To begin, I used isopropyl alcohol on a few cotton rounds and wiped down the stem to provide an initial cleaning of filth before moving on to the next steps. The primary cleaning came next. I disinfected the inside of the stem with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. I scrubbed thoroughly to make sure the interior was very clean. I used quite a few pipe cleaners and cotton swabs – far more than are shown in the photo. The goal of the next step is the removal (or minimization) of oxidation. Going to my sink, I used cream cleanser, cotton rounds, and a toothbrush, and scoured the stem to remove as much surface oxidation as possible. As the photos show, the result was a hideous, ochre-coloured mess – but better off the stem than on it.

The goal of the next step is the removal (or minimization) of oxidation. Going to my sink, I used cream cleanser, cotton rounds, and a toothbrush, and scoured the stem to remove as much surface oxidation as possible. As the photos show, the result was a hideous, ochre-coloured mess – but better off the stem than on it. Once the stem was reasonably clean, I soaked it overnight in some Briarville Stem Oxidation Remover. This solution works to draw oxidation in the stem to the surface of the vulcanite. This is a major aid and an important step in ensuring a clean stem. The following day, I drew out the stem from its bath and scrubbed the lingering fluid with a toothbrush.

Once the stem was reasonably clean, I soaked it overnight in some Briarville Stem Oxidation Remover. This solution works to draw oxidation in the stem to the surface of the vulcanite. This is a major aid and an important step in ensuring a clean stem. The following day, I drew out the stem from its bath and scrubbed the lingering fluid with a toothbrush. As the stem was now clean and dry, I set about fixing the marks and dents in the vulcanite. This was done by filling those divots with black cyanoacrylate adhesive, impregnated with carbon and rubber. I left this to cure and moved on.

As the stem was now clean and dry, I set about fixing the marks and dents in the vulcanite. This was done by filling those divots with black cyanoacrylate adhesive, impregnated with carbon and rubber. I left this to cure and moved on. The penultimate step for the stem is sanding. First, with my set of needle files, I reduced the bulk of the cyanoacrylate repairs. I removed the excess adhesive as near to the surface as possible, without cutting into the vulcanite. Following that, I used all nine of the micromesh sanding pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand out flaws, even out the vulcanite, and provide gentle polishing of the finished surface. I also applied pipe-stem oil while using the last five micromesh pads. There was a wonderful, deep black shine to the stem when I was done.

The penultimate step for the stem is sanding. First, with my set of needle files, I reduced the bulk of the cyanoacrylate repairs. I removed the excess adhesive as near to the surface as possible, without cutting into the vulcanite. Following that, I used all nine of the micromesh sanding pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand out flaws, even out the vulcanite, and provide gentle polishing of the finished surface. I also applied pipe-stem oil while using the last five micromesh pads. There was a wonderful, deep black shine to the stem when I was done. As the stem was (nearly) complete, I moved on to the stummel. The first step was to ream out the bowl – that is to say, remove all the cake inside the bowl. This accomplished a couple of things. First (and most obviously), it cleaned the bowl and provided a refurbished chamber for future smoking. Second, when the old cake was removed, I could inspect the interior walls of the bowl and determine if there was damage or not. I used a reamer, a pipe knife, and a piece of sandpaper taped to a wooden dowel. Collectively, these ensured that all the debris was removed. And – holy moly – there was a lot of debris!

As the stem was (nearly) complete, I moved on to the stummel. The first step was to ream out the bowl – that is to say, remove all the cake inside the bowl. This accomplished a couple of things. First (and most obviously), it cleaned the bowl and provided a refurbished chamber for future smoking. Second, when the old cake was removed, I could inspect the interior walls of the bowl and determine if there was damage or not. I used a reamer, a pipe knife, and a piece of sandpaper taped to a wooden dowel. Collectively, these ensured that all the debris was removed. And – holy moly – there was a lot of debris! Similar to the stem, I then cleaned the stummel with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. With a pipe this dirty, it took quite a while and much cotton to clean.

Similar to the stem, I then cleaned the stummel with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. With a pipe this dirty, it took quite a while and much cotton to clean. I then decided to ‘de-ghost’ the pipe – that is to say, exorcize the remaining filth from the briar. I filled the bowl and the shank with cotton balls, then saturated them with 99% isopropyl alcohol. I let the stummel sit overnight. This caused the remaining oils, tars and smells to leach out into the cotton.

I then decided to ‘de-ghost’ the pipe – that is to say, exorcize the remaining filth from the briar. I filled the bowl and the shank with cotton balls, then saturated them with 99% isopropyl alcohol. I let the stummel sit overnight. This caused the remaining oils, tars and smells to leach out into the cotton. To tidy up the briar, I wiped down the outside, using a solution of a pH-neutral detergent and some distilled water, with cotton rounds. I also used a nylon brush in the crevices of the plateau. This did a good job of cleaning any latent dirt on the surface of the briar. The last step of the cleaning process was to scour the inside of the stummel with the same mild detergent and tube brushes. This was the culmination of a lot of hard work in getting the pipe clean.

To tidy up the briar, I wiped down the outside, using a solution of a pH-neutral detergent and some distilled water, with cotton rounds. I also used a nylon brush in the crevices of the plateau. This did a good job of cleaning any latent dirt on the surface of the briar. The last step of the cleaning process was to scour the inside of the stummel with the same mild detergent and tube brushes. This was the culmination of a lot of hard work in getting the pipe clean. I used all nine micromesh pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand the outside of the stummel and finish it off. This sanding minimizes flaws in the briar and provides a beautiful smoothness to the wood. I rubbed some LBE Before & After Restoration Balm into the briar and let it sit for 30 minutes or so. The balm moisturizes the wood and gives a beautiful depth to the briar. I then buffed the stummel with a microfibre cloth. Just look at that pipe!

I used all nine micromesh pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand the outside of the stummel and finish it off. This sanding minimizes flaws in the briar and provides a beautiful smoothness to the wood. I rubbed some LBE Before & After Restoration Balm into the briar and let it sit for 30 minutes or so. The balm moisturizes the wood and gives a beautiful depth to the briar. I then buffed the stummel with a microfibre cloth. Just look at that pipe!

For the final step, I took the pipe to my bench polisher and carefully buffed it – first with a blue diamond compound, then with three coats of conservator’s wax. This procedure makes the pipe look its best – the stummel sings and the stem glows.

For the final step, I took the pipe to my bench polisher and carefully buffed it – first with a blue diamond compound, then with three coats of conservator’s wax. This procedure makes the pipe look its best – the stummel sings and the stem glows. This Viggo Nielsen Hand-Finished Freehand looks fantastic again and is ready to be enjoyed by its next owner. I am pleased to announce that this pipe is for sale! If you are interested in acquiring it for your collection, please have a look in the ‘Danish’ pipe section of the store here on Steve’s website. You can also email me directly at kenneth@knightsofthepipe.com. The approximate dimensions of the pipe are as follows: length 6⅛ in. (156 mm); height 3 in. (76 mm); bowl diameter 1⅞ in. (46 mm); chamber diameter 1 in. (25 mm). The weight of the pipe is 2¼ oz. (67 g). I hope you enjoyed reading the story of this pipe’s restoration as much as I did restoring it. If you are interested in more of my work, please follow me here on Steve’s website or send me an email. Thank you very much for reading and, as always, I welcome and encourage your comments.

This Viggo Nielsen Hand-Finished Freehand looks fantastic again and is ready to be enjoyed by its next owner. I am pleased to announce that this pipe is for sale! If you are interested in acquiring it for your collection, please have a look in the ‘Danish’ pipe section of the store here on Steve’s website. You can also email me directly at kenneth@knightsofthepipe.com. The approximate dimensions of the pipe are as follows: length 6⅛ in. (156 mm); height 3 in. (76 mm); bowl diameter 1⅞ in. (46 mm); chamber diameter 1 in. (25 mm). The weight of the pipe is 2¼ oz. (67 g). I hope you enjoyed reading the story of this pipe’s restoration as much as I did restoring it. If you are interested in more of my work, please follow me here on Steve’s website or send me an email. Thank you very much for reading and, as always, I welcome and encourage your comments.