by Kenneth Lieblich

Welcome to another installment of my Pipe Incident Reports. The idea, in general, is to provide a brief write-up – focusing on a particular pipe-restoration-related issue – rather than an entire restoration story. I’ve been blessed by a precious few God-given talents in my life, but innovation is not among them. I’m not usually able to come up with groundbreaking ideas to do things differently. Having said that, I do try and improve my repair/restoration skills, techniques, and procedures wherever I can. One can call it kaizen or whatever, but I try to find better ways of restoring pipes. Today, I am attempting to improve the process of repairing stem bite-throughs by incorporating steel mesh. Now, you might be thinking, ‘That’s not a sentence I ever expected to read’, and you are justified in that thought.

Today, I am attempting to improve the process of repairing stem bite-throughs by incorporating steel mesh. Now, you might be thinking, ‘That’s not a sentence I ever expected to read’, and you are justified in that thought.

Many pipe repairmen have used various methods for repairing bite-throughs (holes) in vulcanite. Normally, this involves mixing cyanoacrylate adhesive with activated charcoal or powdered vulcanite. Some fellows have also tried some sort of epoxy to bring the stem back to life. In fact, when I started doing pipe repairs, I used that mixture of cyanoacrylate adhesive and activated charcoal. Then I discovered a black-tinted cyanoacrylate adhesive that came pre-mixed with rubber and charcoal. I introduced this product to Steve and it’s what he and I have been using ever since. However, I have always wondered about the durability of these repairs – especially against the bite of a man’s jaw. I wondered, could there be a better way?

Maybe. Read on, but please note: what I am proposing is NOT a complete solution. This is an idea that I hope someone will take and turn into a workable method.

I decided to test a pipe-stem repair with the aforementioned adhesive built around a stainless-steel wire-mesh structure. My thinking is that this would enhance the strength and durability of said repairs. For any engineers or scientists reading this article, please know that I have no scientific background and I am not equipped to conduct accurate tests of compressive or tensile strength. I am merely running an idea up the proverbial flagpole and seeing who salutes it. I hope that someone reading this will take the idea and, either, discredit it or expand upon it. The experiment I describe below is just that: an experiment. It is, possibly, a proof of concept – but certainly not the final step.

The idea came to me one day as I saw some sort of wire mesh being used in a concrete foundation. This mesh is used in construction to control cracking, to distribute stress, and add tensile strength. Perhaps it can be used, in like manner, where a large vulcanite repair is needed. My encounter with the concrete was providential because I had recently acquired a large lot of pipes, many of which had damaged stems. There was one stem in particular that stood out as a candidate for this experiment. Here it is:

This is a stem that I would normally likely toss in the garbage, unless a customer specifically asked me to repair it. The damage is obviously serious. Ironically, this brutal damage actually makes this stem the perfect patient for this type of surgery.

This is a stem that I would normally likely toss in the garbage, unless a customer specifically asked me to repair it. The damage is obviously serious. Ironically, this brutal damage actually makes this stem the perfect patient for this type of surgery.

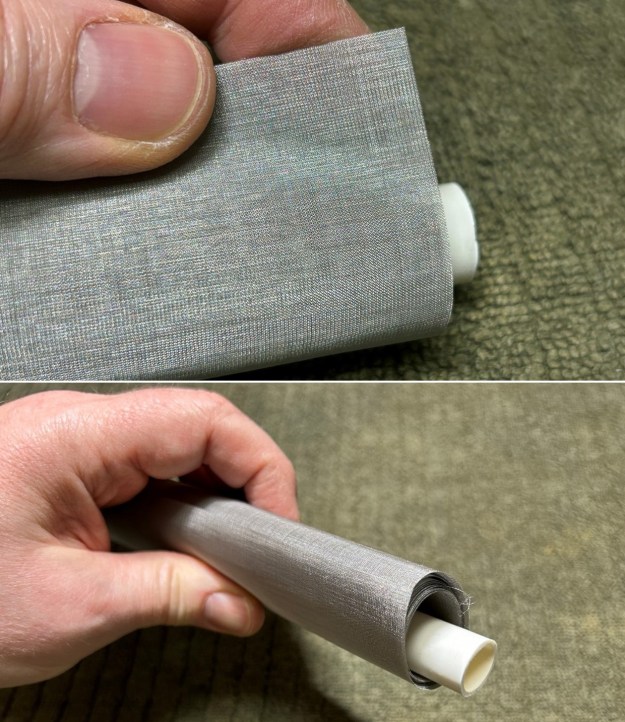

Here is the stainless-steel woven wire mesh. For those of you who know such things, this mesh has a mesh number of 200. It can be acquired inexpensively and comes in various mesh numbers. The larger the number, the finer the holes in the mesh. To be frank, my selection of 200 was pure guesswork. I didn’t really have a sense of what would be best – other than to say that it needed to be fine enough to prevent the adhesive from pouring straight through. On with the work! I first needed to create a platform upon which the adhesive and mesh could rest. This was obviously essential in order to maintain the draught hole in the bit. In the first photo below, you’ll see that I used cardboard, but I immediately abandoned that idea (I’ll explain why momentarily). I am displaying this photo in order to demonstrate my use of a pencil to scribe the precise shape of the missing section of vulcanite.

On with the work! I first needed to create a platform upon which the adhesive and mesh could rest. This was obviously essential in order to maintain the draught hole in the bit. In the first photo below, you’ll see that I used cardboard, but I immediately abandoned that idea (I’ll explain why momentarily). I am displaying this photo in order to demonstrate my use of a pencil to scribe the precise shape of the missing section of vulcanite. I quickly eliminated the cardboard idea because it just isn’t as useful a material for this purpose. Instead, I used several layers of duct tape as my substrate. I can still scribe a line on the duct tape, but – more importantly – cyanoacrylate adhesive doesn’t stick to it. In other words, once the work had fully cured, I could readily remove the duct tape without affecting the repair.

I quickly eliminated the cardboard idea because it just isn’t as useful a material for this purpose. Instead, I used several layers of duct tape as my substrate. I can still scribe a line on the duct tape, but – more importantly – cyanoacrylate adhesive doesn’t stick to it. In other words, once the work had fully cured, I could readily remove the duct tape without affecting the repair.

With my scribed line, I was able to transfer the pattern of the absent vulcanite on to the wire mesh and cut it to shape. Truth be told, it would probably be better to use welded wire mesh, but I have no idea where you acquire that in such a small mesh number. Anyway, before cutting the wire mesh, I took the critical steps of (1) gently sanding the mesh with sandpaper to provide a slightly rough surface to maximize the adhesive bond, and (2) cleaning the mesh thoroughly with acetone, to remove any sanding grit and any other substance that would inhibit a good adhesive bond.

And away we go! It is important to apply the cyanoacrylate adhesive in thin layers, rather than one thick blob. I chose to apply a layer, spray it with an accelerator, apply another layer, etc. – until I was satisfied. Once complete, I left it to sit overnight and came back the next day. I freely admit that I am still concerned about the brittleness of this repair, but I think this is definitely a step in the right direction.

Naturally, shaping and sanding was the next step – and this took a while. I should emphasise at this point that I didn’t employ the same attention to detail on this stem, as I would on a stem for a customer. I just wanted to get this done and see if it would work. As I sanded with needle files and sanding pads, I shaped the button and melded the repair into the surrounding vulcanite. You can see the results below. It’s pretty good and I’m sure it would look even better if I was doing it for sale or for a customer.

Naturally, shaping and sanding was the next step – and this took a while. I should emphasise at this point that I didn’t employ the same attention to detail on this stem, as I would on a stem for a customer. I just wanted to get this done and see if it would work. As I sanded with needle files and sanding pads, I shaped the button and melded the repair into the surrounding vulcanite. You can see the results below. It’s pretty good and I’m sure it would look even better if I was doing it for sale or for a customer.

Some final thoughts: I think there is a rudimentary idea here. I feel confident in saying that the repair itself is likely stronger and more resilient with the mesh than without. However, I am apprehensive about whether the brittleness of the cyanoacrylate adhesive is improved or not – and I’m not sure how to reasonably overcome that issue (other than trying epoxy). Another problem that still exists is that there is no direct connection between the mesh and the pre-existing vulcanite. This surely isn’t helpful. It is at the edges – where the adhesive meets the vulcanite – that the bond must be weakest. Next steps might include (1) embedding the wire mesh in an epoxy – this might be the best way of addressing brittleness; (2) overlaying the wire mesh on the original vulcanite to create a bridge structure (although this creates its own big problems); (3) developing a way of affixing the mesh to the vulcanite.

Now, over to you! What do you think of this idea? How would you improve it? What are the next steps? What colossal errors have I made? Please let me know what you think in the comments below. If you make use of the ideas from this experiment in your pipe work, please let me know how it goes. I hope you enjoyed reading this installment of my Pipe Incident Reports – I look forward to writing more. If you are interested in my work, please follow me here on Steve’s website or email me directly at kenneth@knightsofthepipe.com. Thank you very much for reading and, as always, I welcome and encourage your comments.