by Steve Laug

In November I received an email from Mario about working on some of his Dad’s pipes. Here is what he wrote to me.

I am desperately seeking help restoring and repairing some of my dad’s smoking pipes. I have tried reaching out to the only two known pipe repair establishments I could find in the entire country but one is not currently taking repair orders and the other said she didn’t want to try to repair these pipes without having even seen them. Would you be willing to take on the repairs or can you recommend anyone? Thank you much!!!—Mario

I wrote him back and asked him to send me photos of the pipes. He sent some single photos of the meerschaum bowl and stem, several of the leather clad Canadian and the photo of the rack and six pipes shown below. I looked through the photos and this is what I saw. There were two leather clad pipes a Canadian and a Pot. Both of them were cracked on the shanks and had been self-repaired with wire to hold the cracked shank together. The leather cladding was torn and the stitching was rotten and broken around the bowl. To me they were both unrepairable. There was a lovely older Meerschaum with a horn stem that needed a good cleaning and repairs to the horn stem. There were two Knute Freehand pipes with original stems that were dirty but fixable. The plateau on the smooth one had a large chunk of briar missing. There was a Wilshire Dublin with a chewed and misfit stem. Finally, there was a billiard that had been restemmed with a fancy GBD saddle stem on it. They were a messy lot but I told him to send them on to me. They arrived yesterday and the condition of the pipes in the photos was confirmed. They were a mess and needed much work. I have included Mario’s group photo below to show the lot. I decided to start working on the Dublin second. It was the one on the far left leaning against the left end of the rack in the photo above. It was a Dublin shape with a straight round shank and the stem did not fit in the shank correctly and it had a huge bite through on the topside of it. The bowl had a thick cake on the walls and a heavy lava coat on the rim top. It was internally a mess. The finish was dirty and had grime ground into the sides of the bowl. The shank was not cracked like the previous one and was in good shape. The pipe was stamped on the left side of the shank and read Wilshire in script. There was no other stamping on the shank sides. The stem was the wrong one. The diameter was less than the shank. I would need to fit it with a new stem. I took photos of the pipe when I unpacked it to examine it. I have included those below.

I decided to start working on the Dublin second. It was the one on the far left leaning against the left end of the rack in the photo above. It was a Dublin shape with a straight round shank and the stem did not fit in the shank correctly and it had a huge bite through on the topside of it. The bowl had a thick cake on the walls and a heavy lava coat on the rim top. It was internally a mess. The finish was dirty and had grime ground into the sides of the bowl. The shank was not cracked like the previous one and was in good shape. The pipe was stamped on the left side of the shank and read Wilshire in script. There was no other stamping on the shank sides. The stem was the wrong one. The diameter was less than the shank. I would need to fit it with a new stem. I took photos of the pipe when I unpacked it to examine it. I have included those below.

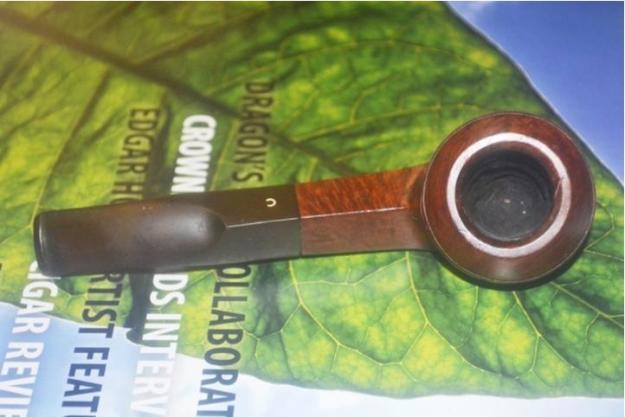

I took a photo of the bowl and rim top to give you and idea of what I see. You can see the thick cake in the bowl and the thick lava overflow on the rim top and inwardly bevelled inner edges of the bowl. There also appears to be damage on the inner edge toward the back of the bowl. I also included photos of the stem. You can see that the stem is not correct. It does not fit the shank and is chewed a long way up the stem top.

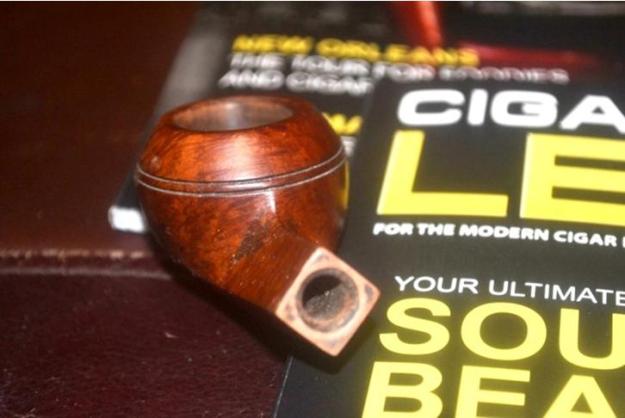

I took a photo of the bowl and rim top to give you and idea of what I see. You can see the thick cake in the bowl and the thick lava overflow on the rim top and inwardly bevelled inner edges of the bowl. There also appears to be damage on the inner edge toward the back of the bowl. I also included photos of the stem. You can see that the stem is not correct. It does not fit the shank and is chewed a long way up the stem top.  I took a photo of the stamping on the left side of the shank. It is clear and readable as noted above. I took a photo of the bowl with the incorrect stem removed to give a sense of the proportion and appearance of the pipe without the stem. You can see the damage on the stem top so it is no question that it needs to be removed.

I took a photo of the stamping on the left side of the shank. It is clear and readable as noted above. I took a photo of the bowl with the incorrect stem removed to give a sense of the proportion and appearance of the pipe without the stem. You can see the damage on the stem top so it is no question that it needs to be removed. I turned to Pipephil’s site to see what I could find out about the Wilshire brand and was not disappointed (http://www.pipephil.eu/logos/en/logo-w3.html). I did a screen capture of the section below. It was good to know that the pipe was made by Comoy’s.

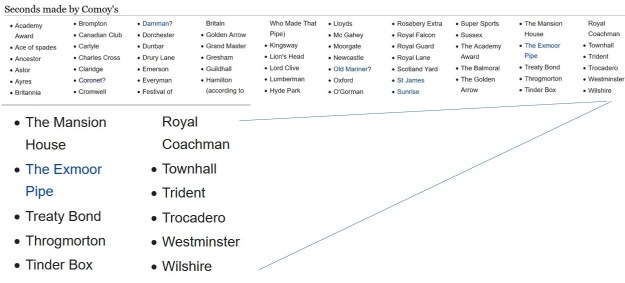

I turned to Pipephil’s site to see what I could find out about the Wilshire brand and was not disappointed (http://www.pipephil.eu/logos/en/logo-w3.html). I did a screen capture of the section below. It was good to know that the pipe was made by Comoy’s. Knowing that the pipe was made by Comoy I turned to the article on Comoy on Pipedia to see what I could learn (https://pipedia.org/wiki/Comoy%27s#Seconds_made_by_Comoy’s). Beside the great history article there was a section with photos toward the end of the article entitled Seconds Made by Comoy’s. There were no photos of the pipe but there was a list of these pipes and the last entry in the list was the Wilshire. The screen capture below shows the list as a whole and I have taken the last two columns and enlarged them below. The last item in the list is this brand of pipe.

Knowing that the pipe was made by Comoy I turned to the article on Comoy on Pipedia to see what I could learn (https://pipedia.org/wiki/Comoy%27s#Seconds_made_by_Comoy’s). Beside the great history article there was a section with photos toward the end of the article entitled Seconds Made by Comoy’s. There were no photos of the pipe but there was a list of these pipes and the last entry in the list was the Wilshire. The screen capture below shows the list as a whole and I have taken the last two columns and enlarged them below. The last item in the list is this brand of pipe. Now that I knew that I was working on a Comoy’s made second pipe and I had a bit of background on it I was ready to start on the pipe itself

Now that I knew that I was working on a Comoy’s made second pipe and I had a bit of background on it I was ready to start on the pipe itself

I reamed the bowl with a PipNet Pipe Reamer to take the cake back to bare briar. I cleaned up the remnants of cake with a Savinelli Fitsall Pipe Knife and removed the remaining debris. I sanded the bowl walls smooth with a piece of 220 grit sandpaper wrapped around a piece of dowel. I scraped the lava coat off the rim top with the Savinelli Pipe Knife and removed all of it.

I scrubbed the externals of the bowl and shank with undiluted Murphy’s Oil Soap and a tooth brush. I worked over the bowl, shank and rim top with the soap and then rinsed it off warm water. The bowl looked extremely good. There were some significant burn marks on the rim top and inner edge but the bowl itself was very clean.

I scrubbed the externals of the bowl and shank with undiluted Murphy’s Oil Soap and a tooth brush. I worked over the bowl, shank and rim top with the soap and then rinsed it off warm water. The bowl looked extremely good. There were some significant burn marks on the rim top and inner edge but the bowl itself was very clean.

I cleaned out the internals of the bowl and shank with pipe cleaners, cotton swabs, shank brushes and 99% isopropyl alcohol. It was very clean and it looked and smelled far better. I really liked the look of the shank band on the shank end.

I cleaned out the internals of the bowl and shank with pipe cleaners, cotton swabs, shank brushes and 99% isopropyl alcohol. It was very clean and it looked and smelled far better. I really liked the look of the shank band on the shank end. I lightly topped the bowl on a topping board with 220 grit sandpaper. I wanted to remove the dips and burned areas from the rim top and flatten it for the next step in the process. I used a half sphere and some 220 grit sandpaper to clean up the inner bevel on the rim edge and smooth out that part of the bowl. It was far from perfect but it was smooth and it was flat.

I lightly topped the bowl on a topping board with 220 grit sandpaper. I wanted to remove the dips and burned areas from the rim top and flatten it for the next step in the process. I used a half sphere and some 220 grit sandpaper to clean up the inner bevel on the rim edge and smooth out that part of the bowl. It was far from perfect but it was smooth and it was flat.

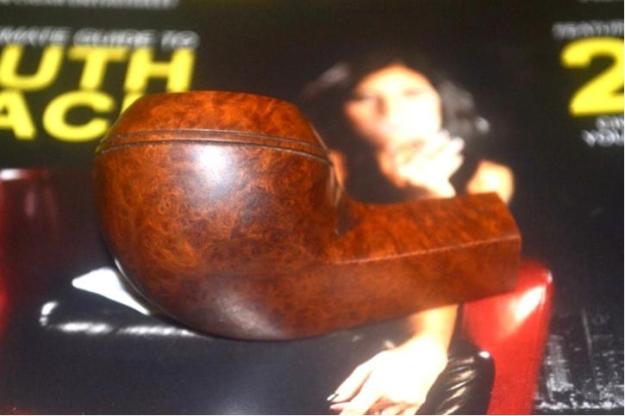

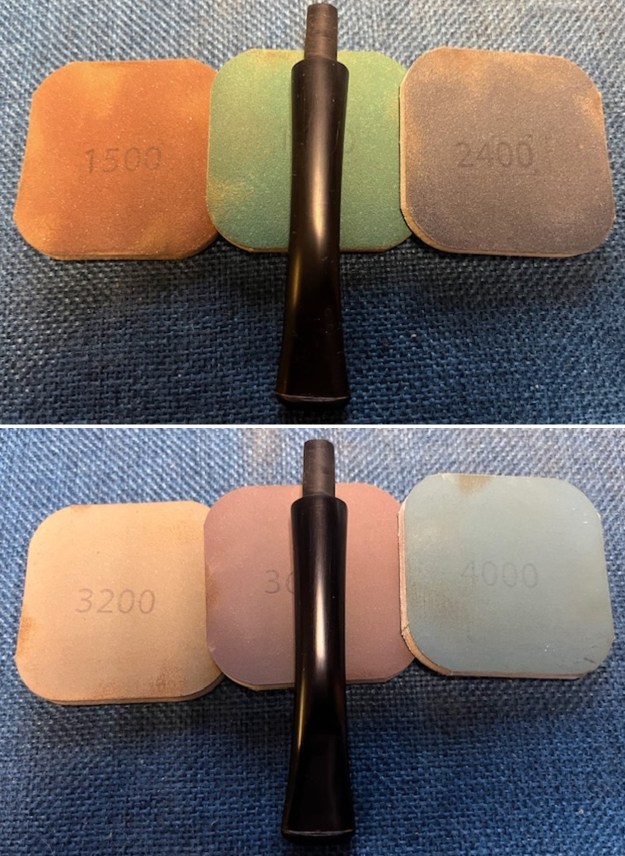

I used 320-3500 grit sanding pads to smooth out the scratches and nicks in the surface of the briar. There were many small scratches and nicks in the briar. I wiped the bowl down after each sanding pad with a damp cloth to remove the sanding dust and debris. It really began to look very good. The grain is quite lovely.

I used 320-3500 grit sanding pads to smooth out the scratches and nicks in the surface of the briar. There were many small scratches and nicks in the briar. I wiped the bowl down after each sanding pad with a damp cloth to remove the sanding dust and debris. It really began to look very good. The grain is quite lovely.

I polished the briar with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding with 1500-12000 grit pads and wiped it down the bowl after each sanding pad.

I polished the briar with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding with 1500-12000 grit pads and wiped it down the bowl after each sanding pad.

I rubbed the bowl and shank down with Before & After Restoration Balm. I worked it into the surface of the bowl sides and shank with my fingertips to clean, enliven and protect the briar. I let the balm sit for a little while and then buffed with a cotton cloth to raise the shine. The Balm did its magic and the grain stood out.

I rubbed the bowl and shank down with Before & After Restoration Balm. I worked it into the surface of the bowl sides and shank with my fingertips to clean, enliven and protect the briar. I let the balm sit for a little while and then buffed with a cotton cloth to raise the shine. The Balm did its magic and the grain stood out.

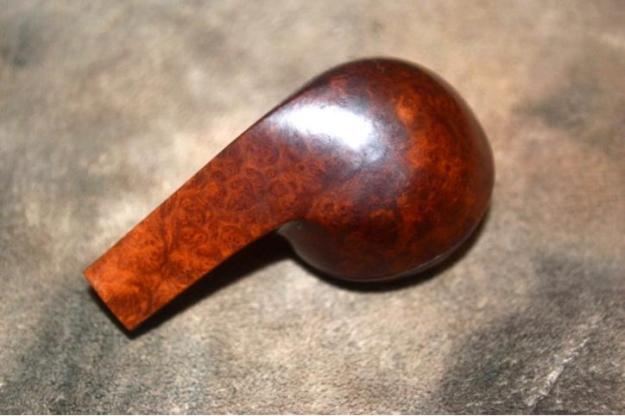

I went through my can of stems and found one that was the right taper for the pipe bowl I was working on. It had the right look and would need shaping. I was not sure that the original stem had been bent so I was uncertain about doing that with this new stem. I may just do it because Mario’s Dad had done it to the pipe when he had it!

I went through my can of stems and found one that was the right taper for the pipe bowl I was working on. It had the right look and would need shaping. I was not sure that the original stem had been bent so I was uncertain about doing that with this new stem. I may just do it because Mario’s Dad had done it to the pipe when he had it!  I cleaned out the internals of the stem with alcohol and pipe cleaners. It was surprisingly clean so it was ready to work on it to make a proper fit.

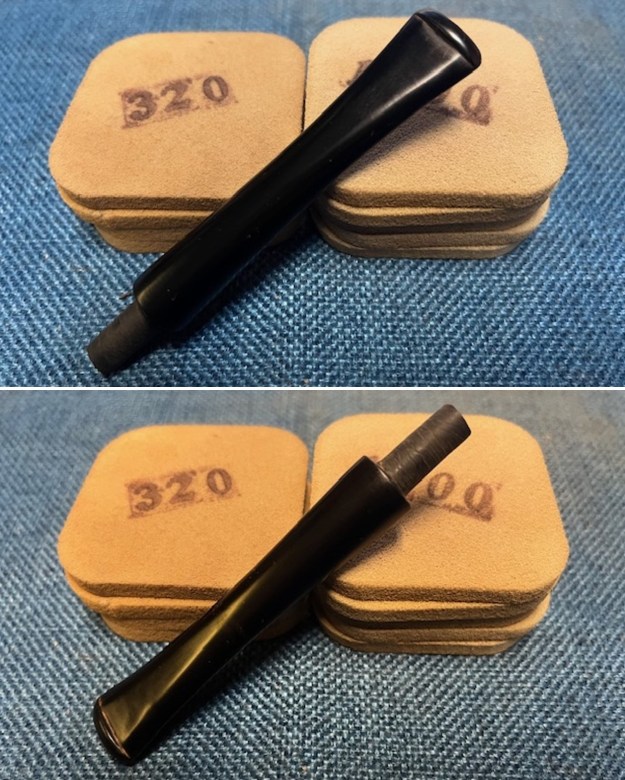

I cleaned out the internals of the stem with alcohol and pipe cleaners. It was surprisingly clean so it was ready to work on it to make a proper fit. I sanded the stem to smooth it out with 320-3500 grit sanding pads. I wiped the stem down after each pad with an Obsidian Oil cloth. It was beginning to look very good.

I sanded the stem to smooth it out with 320-3500 grit sanding pads. I wiped the stem down after each pad with an Obsidian Oil cloth. It was beginning to look very good. I used the lighter to soften the stem enough to bend it the same bend as the other stem had. It looked very good.

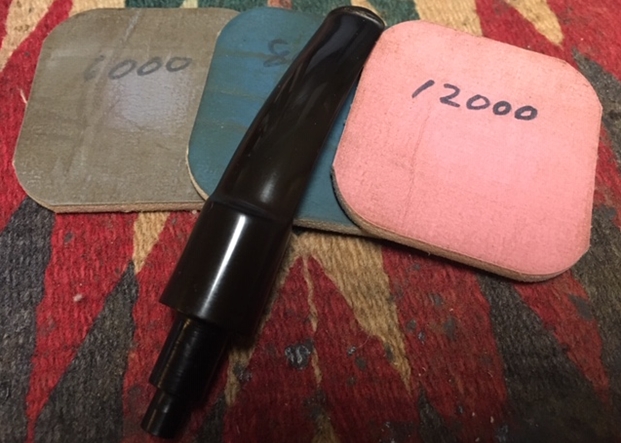

I used the lighter to soften the stem enough to bend it the same bend as the other stem had. It looked very good. I polished the stem with micromesh sanding pads – 1500-12000 grit pads. I wiped it down with a damp cloth after each sanding pad. I used Before & After Pipe Polish – both Fine and Extra Fine to further polish the stem.

I polished the stem with micromesh sanding pads – 1500-12000 grit pads. I wiped it down with a damp cloth after each sanding pad. I used Before & After Pipe Polish – both Fine and Extra Fine to further polish the stem.

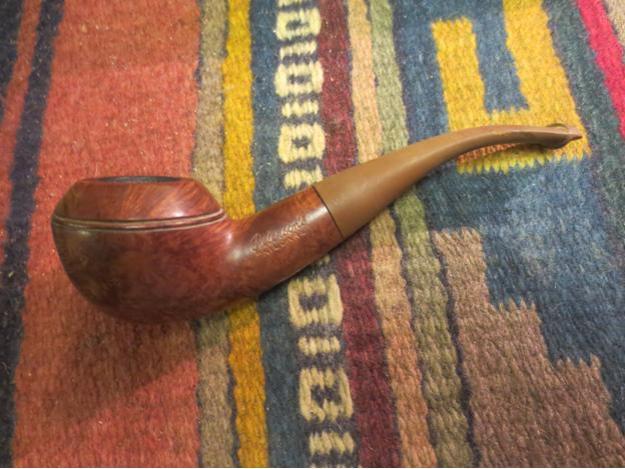

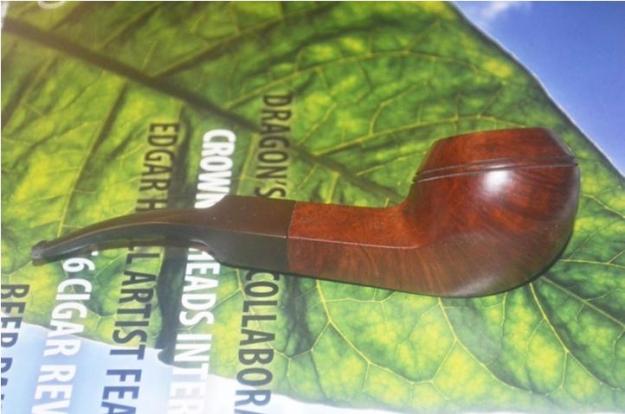

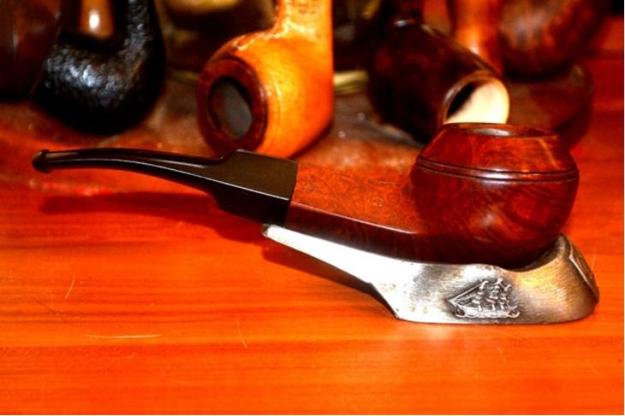

This restored and restemmed Comoy’s Made Wilshire Dublin with a new vulcanite taper stem is a great looking pipe now that it has been restored. The beautiful finish really highlights the grain. I put the stem back on the bowl and carefully buffed the pipe with Blue Diamond on the buffing wheel. I gave the bowl and the stem multiple coats of carnauba wax on the buffing wheel and followed that by buffing the entire pipe with a clean buffing pad. I hand buffed the pipe with a microfiber cloth to deepen the shine. The rim top shows some burns marks that I could not remove as they were very deep. The finished Wilshire Dublin is a beautiful pipe, but it fits nicely in the hand and feels great. Give the finished pipe a look in the photos below. The dimensions of the pipe are Length: 6 inches, Height: 1 ¾ inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 ¼ inches, Chamber diameter: ¾ of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 38 grams /1.31 ounces. This is the second of six pipes that I am restemming and restoring for Mario from his Dad’s collection. I look forward to hearing what he thinks of this newly restemmed pipe. Thanks for reading this blog and my reflections on the pipe while I worked on it.

This restored and restemmed Comoy’s Made Wilshire Dublin with a new vulcanite taper stem is a great looking pipe now that it has been restored. The beautiful finish really highlights the grain. I put the stem back on the bowl and carefully buffed the pipe with Blue Diamond on the buffing wheel. I gave the bowl and the stem multiple coats of carnauba wax on the buffing wheel and followed that by buffing the entire pipe with a clean buffing pad. I hand buffed the pipe with a microfiber cloth to deepen the shine. The rim top shows some burns marks that I could not remove as they were very deep. The finished Wilshire Dublin is a beautiful pipe, but it fits nicely in the hand and feels great. Give the finished pipe a look in the photos below. The dimensions of the pipe are Length: 6 inches, Height: 1 ¾ inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 ¼ inches, Chamber diameter: ¾ of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 38 grams /1.31 ounces. This is the second of six pipes that I am restemming and restoring for Mario from his Dad’s collection. I look forward to hearing what he thinks of this newly restemmed pipe. Thanks for reading this blog and my reflections on the pipe while I worked on it.