by Kenneth Lieblich

I have been restoring pipes for more than five years now, and I have learned everything at the feet of the master: Steve Laug. And, because of him, there is a pipe I have dreamt of finding since I started. Recently, I acquired a large lot of pipes and, as these things often are, the box contained everything from the absurd to the sublime. Quite a few pipes in the box were Danish, so that’s always a delight. When I took the box of pipes home, I didn’t realize it, but the pipe of my dreams was inside.

Perhaps I should be more explicit in what I’m talking about. In essence, I have always wanted to find a pipe that Steve really wanted – so I could give it to him. In the world of pipes, Steve has really been-there, done-that. Steve has seen it all (or just about all), and it was always going to be a tall order to find a pipe he wanted that he hadn’t owned before or seen before. This box of pipes had it! Steve told me that he always wanted a pipe from Danish master carver Åge Bøgelund. Turns out, there was one in this box. I grabbed it, restored it, and presented it to him as a gift. It seemed the least I could do in thanks for all he’s done for me.

Let me take a moment to tell you a little bit about the pipe maker, Åge Bøgelund. There isn’t much information available, but here’s what I found. From Pipedia:

Let me take a moment to tell you a little bit about the pipe maker, Åge Bøgelund. There isn’t much information available, but here’s what I found. From Pipedia:

Åge Bogelund was in charge of the Bari factory after Viggo Nielsen. During factory operation and after the factory closed he made some handmade pipes stamped with his name, some are quite large and some are very unique. They are scarce and have become collectible.

From 1978 to 1993 Åge Bogelund and Helmer Thomsen headed Bari’s pipe production. Helmer Thomson bought the company in 1993 re-naming it to “Bari Piber Helmer Thomsen”. The workshop moved to more convenient buildings in Vejen. Bogelund created very fine freehands of his own during the time at Bari.

Next, from MBSD Pipes:

Age (or rather, Åge) Bogelund is a somewhat less known carver from the 20th century Danish pipe-making tradition – though he was no less a master than his contemporaries. Originally, he worked for Viggo Nielsen’s Bari pipe company, being charged with making some of its higher-grade freehands. Later, Bogelund made pipes under his own name, each displaying a distinct style and talent, even among his celebrated Danish peers. Bogelund’s pipes have for a long time been coveted by collectors, though in more recent years, these creations have attracted a more popular enthusiasm.

Next, from SmokingPipes:

We haven’t seen many Åge Bogelund pipes come through our estate department, so this intricate Freehand makes for a rare and welcomed sight. The Danish carver was in charge of Bari at one point, having headed up the marque’s pipe production alongside Helmer Thomsen before Thomsen bought the company in 1993. During his time there, though, Bogelund fashioned his own pipes as well, which have since become quite collectible. Many are large and quite unique, as Åge rendered many Freehands.

You get the idea: his pipes are well-regarded and rare.

So, let’s take a closer look at this pipe. It really is a beauty and, if Steve hadn’t wanted it, I would certainly have kept it for myself. What would you call this shape? It’s probably a freehand brandy.

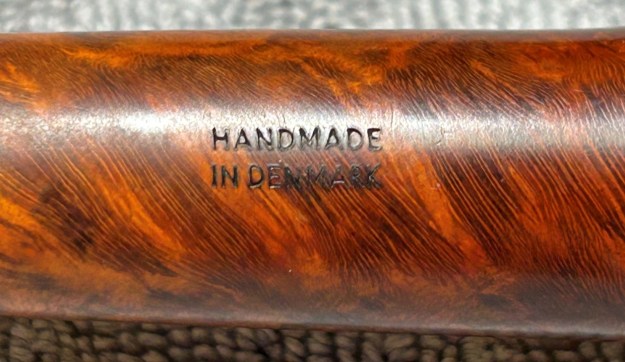

The markings are very clear. On the left side of the shank, we see Åge [over] Bøgelund – written in a semi-circle. To the right of that, are the initials DB. On the right side of the shank, we see Handmade [over] in Denmark. Finally, on the underside of the shank, we see the initials EN. Despite much investigation, I cannot determine what the initials DB or EN are meant to represent. I wondered if DB was meant to signify Design Berlin – the connection is possible but tenuous. Google’s AI function suggested that there was a connection (without any source references), which makes me think this info from Google AI represents another pair of letters: the first being a B and the second being an S.

I am pleased to report that the condition of the pipe is good. The stem obviously had a Softy Bit on it (Deo gratias). I’m pleased because it protected the bit from too much damage. The stem has quite a bit of calcification on it, but not too much oxidation. The stummel is dirty, but sound. There is plenty of cake in the bowl, and a good amount of lava on the rim. There is minor wear to the briar for the most part – except for a small cut on one side.

I am pleased to report that the condition of the pipe is good. The stem obviously had a Softy Bit on it (Deo gratias). I’m pleased because it protected the bit from too much damage. The stem has quite a bit of calcification on it, but not too much oxidation. The stummel is dirty, but sound. There is plenty of cake in the bowl, and a good amount of lava on the rim. There is minor wear to the briar for the most part – except for a small cut on one side.

The stem’s calcification was notable. I used an old butter knife and gently scraped some of the thicker accretion off. Doing this now helps later in removing the oxidation.

The stem’s calcification was notable. I used an old butter knife and gently scraped some of the thicker accretion off. Doing this now helps later in removing the oxidation.  I used isopropyl alcohol on a few cotton rounds and wiped down the stem to provide an initial cleaning of filth before moving on to the next steps. The primary cleaning came next. I disinfected the inside of the stem with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. I scrubbed thoroughly to make sure the interior was very clean.

I used isopropyl alcohol on a few cotton rounds and wiped down the stem to provide an initial cleaning of filth before moving on to the next steps. The primary cleaning came next. I disinfected the inside of the stem with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. I scrubbed thoroughly to make sure the interior was very clean. The goal of the next step is the removal (or minimization) of oxidation. Going to my sink, I used cream cleanser, cotton rounds, and a toothbrush, and scoured the stem to remove as much surface oxidation as possible. As the photos show, the result was a hideous, ochre-coloured mess – but better off the stem than on it.

The goal of the next step is the removal (or minimization) of oxidation. Going to my sink, I used cream cleanser, cotton rounds, and a toothbrush, and scoured the stem to remove as much surface oxidation as possible. As the photos show, the result was a hideous, ochre-coloured mess – but better off the stem than on it. Once the stem was reasonably clean, I soaked it overnight in some Briarville Stem Oxidation Remover. This solution works to draw oxidation in the stem to the surface of the vulcanite. This is a major aid and an important step in ensuring a clean stem. The following day, I drew out the stem from its bath and scrubbed the lingering fluid with a toothbrush.

Once the stem was reasonably clean, I soaked it overnight in some Briarville Stem Oxidation Remover. This solution works to draw oxidation in the stem to the surface of the vulcanite. This is a major aid and an important step in ensuring a clean stem. The following day, I drew out the stem from its bath and scrubbed the lingering fluid with a toothbrush. As the stem was now clean and dry, I set about fixing the marks and dents in the vulcanite. This was done by filling those divots with black cyanoacrylate adhesive, impregnated with carbon and rubber. I left this to cure and moved on.

As the stem was now clean and dry, I set about fixing the marks and dents in the vulcanite. This was done by filling those divots with black cyanoacrylate adhesive, impregnated with carbon and rubber. I left this to cure and moved on. The penultimate step for the stem is sanding. First, with my set of needle files, I reduced the bulk of the cyanoacrylate repairs. I removed the excess adhesive as near to the surface as possible, without cutting into the vulcanite. Following that, I used all nine of the micromesh sanding pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand out flaws, even out the vulcanite, and provide gentle polishing of the finished surface. I also applied pipe-stem oil while using the last five micromesh pads. There was a wonderful, deep black shine to the stem when I was done.

The penultimate step for the stem is sanding. First, with my set of needle files, I reduced the bulk of the cyanoacrylate repairs. I removed the excess adhesive as near to the surface as possible, without cutting into the vulcanite. Following that, I used all nine of the micromesh sanding pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand out flaws, even out the vulcanite, and provide gentle polishing of the finished surface. I also applied pipe-stem oil while using the last five micromesh pads. There was a wonderful, deep black shine to the stem when I was done. As the stem was (nearly) complete, I moved on to the stummel. The first step was to ream out the bowl – that is to say, remove all the cake inside the bowl. This accomplished a couple of things. First (and most obviously), it cleaned the bowl and provided a refurbished chamber for future smoking. Second, when the old cake was removed, I could inspect the interior walls of the bowl and determine if there was damage or not. I used a reamer, a pipe knife, and a piece of sandpaper taped to a wooden dowel. Collectively, these ensured that all the debris was removed.

As the stem was (nearly) complete, I moved on to the stummel. The first step was to ream out the bowl – that is to say, remove all the cake inside the bowl. This accomplished a couple of things. First (and most obviously), it cleaned the bowl and provided a refurbished chamber for future smoking. Second, when the old cake was removed, I could inspect the interior walls of the bowl and determine if there was damage or not. I used a reamer, a pipe knife, and a piece of sandpaper taped to a wooden dowel. Collectively, these ensured that all the debris was removed. My next step was to remove the lava on the rim. For this, I took a piece of machine steel and gently scraped the lava away. The metal’s edge is sharp enough to remove what I need, but not so sharp that it damages the rim.

My next step was to remove the lava on the rim. For this, I took a piece of machine steel and gently scraped the lava away. The metal’s edge is sharp enough to remove what I need, but not so sharp that it damages the rim. Similar to the stem, I then cleaned the stummel with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. With a pipe this dirty, it took quite a while and much cotton to clean.

Similar to the stem, I then cleaned the stummel with both pipe cleaners and cotton swabs dipped in lemon-infused 99% isopropyl alcohol. With a pipe this dirty, it took quite a while and much cotton to clean. I then decided to ‘de-ghost’ the pipe – that is to say, exorcize the remaining filth from the briar. I filled the bowl and the shank with cotton balls, then saturated them with 99% isopropyl alcohol. I let the stummel sit overnight. This caused the remaining oils, tars and smells to leach out into the cotton.

I then decided to ‘de-ghost’ the pipe – that is to say, exorcize the remaining filth from the briar. I filled the bowl and the shank with cotton balls, then saturated them with 99% isopropyl alcohol. I let the stummel sit overnight. This caused the remaining oils, tars and smells to leach out into the cotton. To tidy up the briar, I wiped down the outside, using a solution of a pH-neutral detergent and some distilled water, with cotton rounds. I also used a toothbrush in the crevices. This did a good job of cleaning any latent dirt on the surface of the briar. The last step of the cleaning process was to scour the inside of the stummel with the same mild detergent and tube brushes. This was the culmination of a lot of hard work in getting the pipe clean.

To tidy up the briar, I wiped down the outside, using a solution of a pH-neutral detergent and some distilled water, with cotton rounds. I also used a toothbrush in the crevices. This did a good job of cleaning any latent dirt on the surface of the briar. The last step of the cleaning process was to scour the inside of the stummel with the same mild detergent and tube brushes. This was the culmination of a lot of hard work in getting the pipe clean. Having completed that, I was able to address the nicks on the rim and the bowl. I dug out my iron and a damp cotton flannel cloth. By laying the cloth over the affected areas and applying the iron to it, the hot and moist steam can cause the wood to swell slightly and return to shape. There was some improvement – not a lot, but it was better than doing nothing. I forgot to take a photo, however.

Having completed that, I was able to address the nicks on the rim and the bowl. I dug out my iron and a damp cotton flannel cloth. By laying the cloth over the affected areas and applying the iron to it, the hot and moist steam can cause the wood to swell slightly and return to shape. There was some improvement – not a lot, but it was better than doing nothing. I forgot to take a photo, however.

I used all nine micromesh pads (1,500 through 12,000 grit) to sand the outside of the stummel and finish it off. This sanding minimizes flaws in the briar and provides a beautiful smoothness to the wood. I rubbed some LBE Before & After Restoration Balm into the briar and let it sit for 30 minutes or so. The balm moisturizes the wood and gives a beautiful depth to the briar. I then buffed the stummel with a microfibre cloth.

For the final step, I took the pipe to my bench polisher and carefully buffed it – first with a blue diamond compound, then with three coats of carnauba wax. This procedure makes the pipe look its best – the stummel sings and the stem glows.

For the final step, I took the pipe to my bench polisher and carefully buffed it – first with a blue diamond compound, then with three coats of carnauba wax. This procedure makes the pipe look its best – the stummel sings and the stem glows. All done! This Åge Bøgelund freehand brandy pipe looks fantastic again and is ready to be given to Steve. It was a pleasure to work on. It’s a gorgeous pipe. The approximate dimensions of the pipe are as follows: length 6 in. (153 mm); height 2⅛ in. (53 mm); bowl diameter 1¾ in. (44 mm); chamber diameter ¾ in. (19 mm). The weight of the pipe is 2⅛ oz. (61 g). I hope you enjoyed reading the story of this pipe’s restoration as much as I enjoyed restoring it. If you are interested in more of my work, please follow me here on Steve’s website or send me an email at kenneth@knightsofthepipe.com. Thank you very much for reading and, as always, I welcome and encourage your comments.

All done! This Åge Bøgelund freehand brandy pipe looks fantastic again and is ready to be given to Steve. It was a pleasure to work on. It’s a gorgeous pipe. The approximate dimensions of the pipe are as follows: length 6 in. (153 mm); height 2⅛ in. (53 mm); bowl diameter 1¾ in. (44 mm); chamber diameter ¾ in. (19 mm). The weight of the pipe is 2⅛ oz. (61 g). I hope you enjoyed reading the story of this pipe’s restoration as much as I enjoyed restoring it. If you are interested in more of my work, please follow me here on Steve’s website or send me an email at kenneth@knightsofthepipe.com. Thank you very much for reading and, as always, I welcome and encourage your comments.