by Steve Laug

I chose to work on another Canadian Made Brigham to work on next. The pipe is a Freehand Acorn shaped bowl with a carved faux plateau rim top and shank end. We picked it up from a seller in Annapolis Valley, Nova Scotia, Canada on 01/31/2023. It is a neat looking pipe with real character. The shape of the bowl reminded me of some of the Danish Stanwell pipes that I have restored. I did the research on it. It is stamped Brigham [over] Made in Canada on the underside of the shank and has the shape number 9W2 stamped to the left of that. The stem has three brass pins on the left side of the blade of the fancy saddle. There was a heavy cake in the bowl and a lot of lava overflow on the rim top and edges. The rustication on the rim top is a faux plateau look and it has a smooth finish on the bowl and shank. I think that there was a beautiful pipe underneath all of the buildup of years of use. The stem was oxidized and had tooth marks on the top and underside of the stem ahead of the button. It was a mess. Jeff took photos of the pipe before he started his cleanup work on it.

Jeff took photos of the bowl and rim top to show the condition of the bowl with the thick cake in the bowl and a thick overflow of lava on the rim top. He took photos of the top and underside of the stem showing the tooth marks on the top and underside as well as on the button surface.

Jeff took photos of the bowl and rim top to show the condition of the bowl with the thick cake in the bowl and a thick overflow of lava on the rim top. He took photos of the top and underside of the stem showing the tooth marks on the top and underside as well as on the button surface.

Jeff removed the stem and it had the Brigham Hard Rock Maplewood Distillator aluminum tenon. It had an old wooden Distillator in the tenon that was quite dirty.

Jeff removed the stem and it had the Brigham Hard Rock Maplewood Distillator aluminum tenon. It had an old wooden Distillator in the tenon that was quite dirty.  Jeff took photos of the sides and heel of the bowl to show the condition of the finish. Even under the dirt and debris of the years the grain on the smooth briar looked very good.

Jeff took photos of the sides and heel of the bowl to show the condition of the finish. Even under the dirt and debris of the years the grain on the smooth briar looked very good.

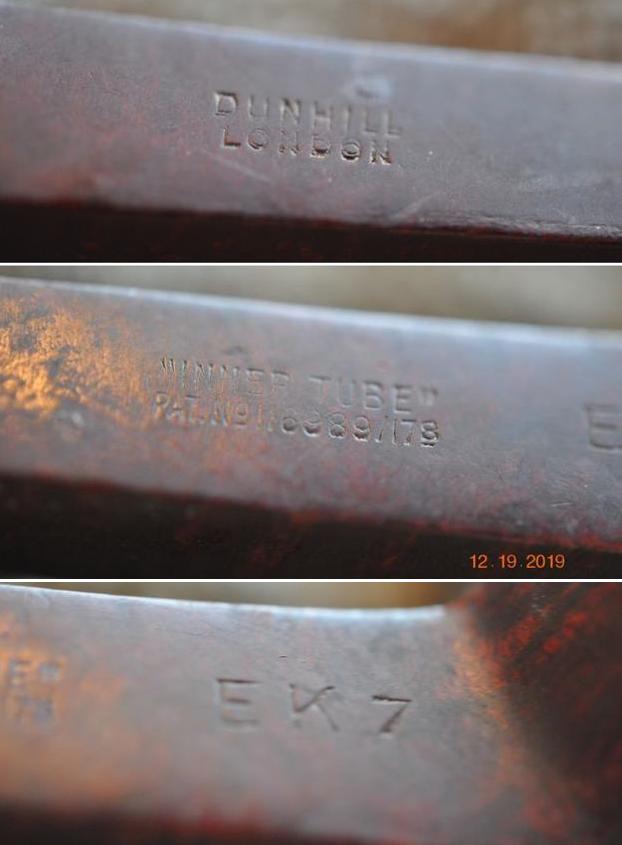

The stamping is very clear and reads as noted above. He included a pic of the 3 brass dots on the stem.

The stamping is very clear and reads as noted above. He included a pic of the 3 brass dots on the stem. For the needed background I am including the information from Pipedia on Brigham pipes. It is a great read in terms of the history of the brand (https://pipedia.org/wiki/Brigham_Pipes). Charles Lemon (Dadspipes) is currently working on a book on the history of the brand. Until that is complete this article is a good summary. I have included it below.

For the needed background I am including the information from Pipedia on Brigham pipes. It is a great read in terms of the history of the brand (https://pipedia.org/wiki/Brigham_Pipes). Charles Lemon (Dadspipes) is currently working on a book on the history of the brand. Until that is complete this article is a good summary. I have included it below.

Roy Brigham, after serving an apprenticeship under an Austrian pipesmith, started his own pipe repair shop in Toronto, in 1906. By 1918 the business had grown to include five other craftsmen and had developed a reputation across Canada for the high quality of workmanship. After repairing many different brands of pipes over the years, Roy noted certain recurring complaints by pipe smokers, the most common referred to as “tongue bite”. Tongue bite is a burning sensation on the smoker’s tongue, previously thought to be due to the heat of the smoke (i.e. a “hot smoking pipe”).

He soon began manufacturing his own pipes, which were lightweight, yet featured a more rugged construction, strengthening the weak points observed in other pipes. The problem of tongue bite intrigued him, and he decided to make overcoming it a future goal.

About 1938, Roy’s son Herb joined him to assist in the business. The business barely survived the great depression because pipes were considered to be a luxury, not a necessity, and selling pipes was difficult indeed. In approximately 1937 [1], after some experimentation, Roy and Herb discovered that tongue bite was in fact a form of mild chemical burn to the tongue, caused by tars and acids in the smoke. They found that by filtering the smoke, it was possible to retain the flavour of the tobacco and yet remove these impurities and thereby stop the tongue bite.

Just as Thomas Edison had searched far and wide for the perfect material from which to make the first electric light bulb filaments, Roy & Herb began experimenting with many materials, both common and exotic, in the quest for the perfect pipe filter. Results varied wildly. Most of the materials didn’t work at all and some actually imparted their own flavour into the smoke. They eventually found just two materials that were satisfactory in pipes: bamboo and rock maple. As bamboo was obviously not as readily available, rock maple then became the logical choice.

They were able to manufacture a replaceable hollow wooden tube made from rock maple dowelling, which when inserted into a specially made pipe, caused absolutely no restriction to the draw of the pipe, yet extracted many of the impurities which had caused tongue bite. The result was indeed a truly better smoking pipe…

With the information I knew what I was dealing with in terms of the stamping and the age of this pipe. I learned that the pipe was originally carved from surplus stummels left over from the Norseman and Valhalla lines. It was made in the 1980-90s because of the stamping on the shank. Now it was time to work on the pipe.

I am really happy to have Jeff’s help on cleaning up the pipes that we pick up along the way. He cleaned this filthy pipe with his usual penchant for thoroughness that I really appreciate. This one was a real mess and I did not know what to expect when I unwrapped it from his box. He reamed it with a PipNet pipe reamer and cleaned up the reaming with a Savinelli Fitsall Pipe Knife. He scrubbed out the internals with alcohol, pipe cleaners and cotton swabs until the pipe was clean. He scrubbed the exterior of the bowl with Murphy’s Oil Soap and a tooth brush to remove the grime and grit on the briar and the lava on the rim top. The finish looks very good with great looking grain around the top half of the bowl and great rustication on the rest of the bowl and shank. Jeff soaked the stem in Before & After Deoxidizer to remove the oxidation on the rubber. He scrubbed it with Soft Scrub All Purpose Cleaner to remove the majority of the oxidation. When the pipe arrived here in Vancouver it looked very good. I took some close up photos of the pipe before I started my part of the restoration.

I took photos of the bowl and rim top as well as both sides of the stem to show its condition. The rim top and edges show a darkening on the plateau but the inner edge looks good. I took close up photos of the stem to show the tooth marks and chatter on the top and underside of the stem and on the button itself.

I took photos of the bowl and rim top as well as both sides of the stem to show its condition. The rim top and edges show a darkening on the plateau but the inner edge looks good. I took close up photos of the stem to show the tooth marks and chatter on the top and underside of the stem and on the button itself.  I took a photo of the stamping on the underside of the shank. It is stamped as noted above and is clear and readable even though faint in spots. I took the pipe apart and took a photo of the pipe. It is an interesting pipe that you can see the grain in the photo below.

I took a photo of the stamping on the underside of the shank. It is stamped as noted above and is clear and readable even though faint in spots. I took the pipe apart and took a photo of the pipe. It is an interesting pipe that you can see the grain in the photo below. I decided to start my restoration work on this one by cleaning up the plateau rim top and shank end with a brass bristle wire brush. I scrubbed it to remove more of the debris and darkening. When I had finished it looked much better.

I decided to start my restoration work on this one by cleaning up the plateau rim top and shank end with a brass bristle wire brush. I scrubbed it to remove more of the debris and darkening. When I had finished it looked much better. I touched up the plateau on the rim top and shank end with a black Sharpie Pen. It gives the plateau depth and great look.

I touched up the plateau on the rim top and shank end with a black Sharpie Pen. It gives the plateau depth and great look.  I sanded the scratches and marks on bowl sides and shank with 320-3500 grit 2×2 inch sanding pads. I wiped it down after each pad with a damp cloth. It really began to shine.

I sanded the scratches and marks on bowl sides and shank with 320-3500 grit 2×2 inch sanding pads. I wiped it down after each pad with a damp cloth. It really began to shine.

I polished the bowl sides and shank with micromesh sanding pads. I dry sanded it with 1500-12000 grit micromesh pads. I wiped it down with a damp cloth after each pad. It really began to look beautiful.

I polished the bowl sides and shank with micromesh sanding pads. I dry sanded it with 1500-12000 grit micromesh pads. I wiped it down with a damp cloth after each pad. It really began to look beautiful.

I rubbed the bowl and shank down with Before & After Restoration Balm to deep clean the finish on the bowl and shank. I worked it in with my fingers to get it into the briar. I worked it into the plateau rim top and shank end with a shoe brush. The product works to clean, enliven and protect the briar. I let it sit for 10 minutes then I wiped it off and buffed it with a soft cloth. The briar really began to have a rich shine. I took some photos of the bowl at this point to mark the progress in the restoration. It is a beautiful bowl.

I rubbed the bowl and shank down with Before & After Restoration Balm to deep clean the finish on the bowl and shank. I worked it in with my fingers to get it into the briar. I worked it into the plateau rim top and shank end with a shoe brush. The product works to clean, enliven and protect the briar. I let it sit for 10 minutes then I wiped it off and buffed it with a soft cloth. The briar really began to have a rich shine. I took some photos of the bowl at this point to mark the progress in the restoration. It is a beautiful bowl.

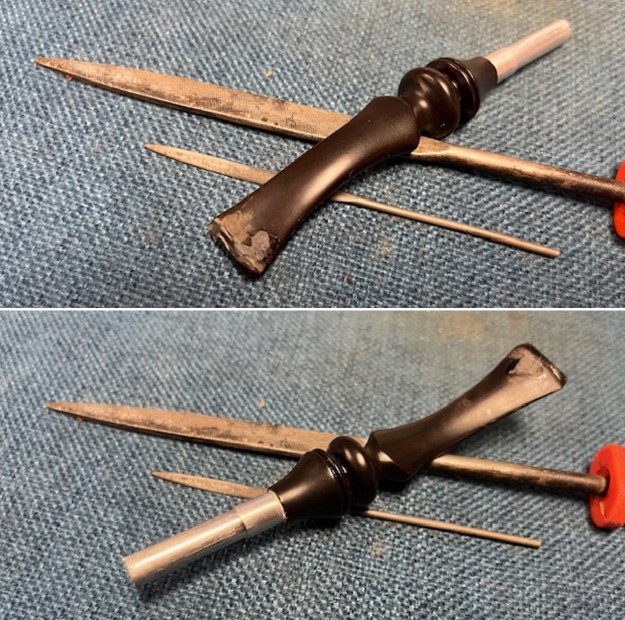

I set the finished bowl aside and turned my attention to the stem. I filled in the deep tooth marks on the top and the underside of the stem with a black rubberized CA glue. Once it cured I shaped it with small files and then sanded the repairs with 220 grit sandpaper to blend it into the vulcanite.

I set the finished bowl aside and turned my attention to the stem. I filled in the deep tooth marks on the top and the underside of the stem with a black rubberized CA glue. Once it cured I shaped it with small files and then sanded the repairs with 220 grit sandpaper to blend it into the vulcanite.

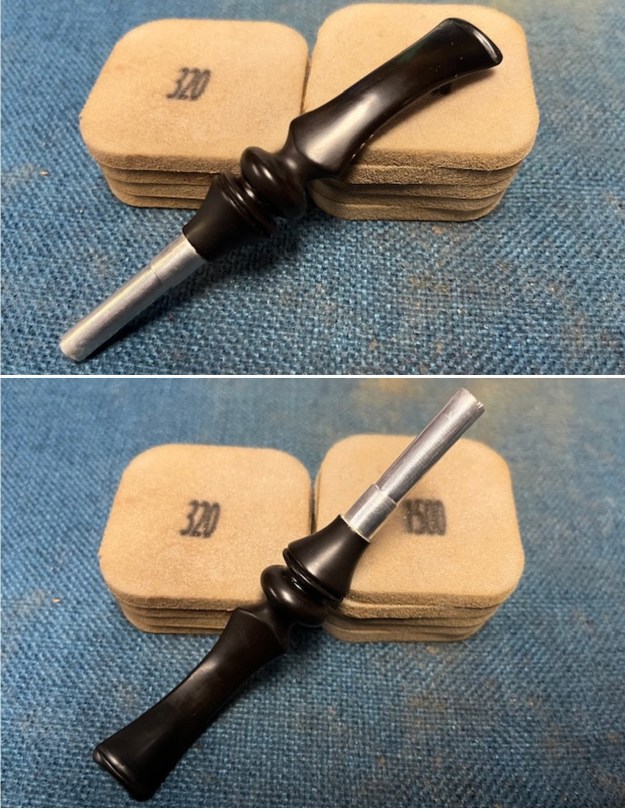

I sanded the stem with 2 x 2 inch sanding pads – dry sanding with 320-3500 grit pads and wiping it down after each pad with an Obsidian Oil cloth.

I sanded the stem with 2 x 2 inch sanding pads – dry sanding with 320-3500 grit pads and wiping it down after each pad with an Obsidian Oil cloth.  I fit the aluminum tenon with a new Rock Maple Distillator tube so it would be ready to go.

I fit the aluminum tenon with a new Rock Maple Distillator tube so it would be ready to go. I polished the stem with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding with 1500-12000 grit pads. I wiped the stem down after each sanding pad with Obsidian Oil. I did a final hand polish of the stem with Before & After Pipe Stem Polish – both Fine and Extra Fine. I gave it a coat of Obsidian Pipe Stem Oil. It works to protect the stem from oxidizing. I set it aside to dry.

I polished the stem with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding with 1500-12000 grit pads. I wiped the stem down after each sanding pad with Obsidian Oil. I did a final hand polish of the stem with Before & After Pipe Stem Polish – both Fine and Extra Fine. I gave it a coat of Obsidian Pipe Stem Oil. It works to protect the stem from oxidizing. I set it aside to dry.

I am excited to finish this Brigham 9W2 Danish Style Freehand – as I think it is an interesting looking pipe that was on the market as a means of using up extra stummels from the Norseman and Vahalla lines that Brigham made. I put the pipe back together and buffed it with Blue Diamond on the buffing wheel. I gave the bowl and the stem multiple coats of carnauba wax. I buffed it with a clean buffing pad to raise the shine. I hand buffed the pipe with a microfiber cloth to deepen it. It is fun to see what the polished bowl looks like with the grain popping through on the bowl and shank. Added to that the polished, rebuilt black vulcanite stem with four shining brass pins was beautiful. This Brigham 9W2 Freehand is nice looking and the pipe feels great in my hand. It is light and well balanced. Have a look at it with the photos below. The dimensions are Length: 5 ¾ inches, Height: 2 inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 ¼ inches, Chamber diameter: ¾ of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 47 grams/1.66 ounces. It is a beautiful pipe and one that will be on the rebornpipes store soon. If you are interested in adding it to your collection let me know. Thanks for walking through the restoration with me as I worked over this pipe. Thanks to each of you who are reading this blog.

I am excited to finish this Brigham 9W2 Danish Style Freehand – as I think it is an interesting looking pipe that was on the market as a means of using up extra stummels from the Norseman and Vahalla lines that Brigham made. I put the pipe back together and buffed it with Blue Diamond on the buffing wheel. I gave the bowl and the stem multiple coats of carnauba wax. I buffed it with a clean buffing pad to raise the shine. I hand buffed the pipe with a microfiber cloth to deepen it. It is fun to see what the polished bowl looks like with the grain popping through on the bowl and shank. Added to that the polished, rebuilt black vulcanite stem with four shining brass pins was beautiful. This Brigham 9W2 Freehand is nice looking and the pipe feels great in my hand. It is light and well balanced. Have a look at it with the photos below. The dimensions are Length: 5 ¾ inches, Height: 2 inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 ¼ inches, Chamber diameter: ¾ of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 47 grams/1.66 ounces. It is a beautiful pipe and one that will be on the rebornpipes store soon. If you are interested in adding it to your collection let me know. Thanks for walking through the restoration with me as I worked over this pipe. Thanks to each of you who are reading this blog.