by Steve Laug

This afternoon after work I decided to work on the pipe that we picked up from our contact in Copenhagen, Denmark on 08/09/2024. It was one that was in rough shape. I think that probably it was a beautifully grained oval shank Brandy with a vulcanite taper stem when it was purchased. It has travelled a hard road before it even made the journey from Copenhagen to us. The pipe is stamped on the left side of the and reads 780 F/T [followed by] Dunhill [over] Bruyere. On the right side of the shank it is stamped Made in England (three lines) [followed by] 4 in a circle [followed by] A. There did not seem to be any date number following the D in England. The briar is in rough condition and dirty from use with a moderate cake in the bowl and a light overflow of lava on the rim top as well as damage on the crowned rim top. In one of the photos Jeff included there was what appeared to be a hairline crack in the side of the bowl. There is a shank repair rejoining the bowl and shank. It is well done. The stem fit well against the shank end. The vulcanite taper stem was oxidized, calcified and had some light tooth chatter on the top and underside of the stem ahead of the button. There was a Dunhill White Spot logo in the top of the stem. Judging from the repairs and the crack it was obviously someone’s favourite pipe and deserved some attention. Jeff took photos of the pipe before he started his clean up work on it. I have included them below.

Jeff took some close up photos of the bowl and rim top. You can see the damage on the crowned rim top. The inner edge of the rim shows some damage around the entire inner edge. There appears to also be some damage on the outer edge as well. The photos of the stem show the oxidation, calcification and tooth marks on the stem ahead of the button.

Jeff took some close up photos of the bowl and rim top. You can see the damage on the crowned rim top. The inner edge of the rim shows some damage around the entire inner edge. There appears to also be some damage on the outer edge as well. The photos of the stem show the oxidation, calcification and tooth marks on the stem ahead of the button.

Jeff took photos of the sides of the bowl to show the interesting grain on the Brandt shaped bowl and shank. It appears that there is either a hairline crack in the bowl side of perhaps it is deep scratch. I will check that once the pipe arrives.

Jeff took photos of the sides of the bowl to show the interesting grain on the Brandt shaped bowl and shank. It appears that there is either a hairline crack in the bowl side of perhaps it is deep scratch. I will check that once the pipe arrives.

Jeff also captured a look at the left side of the bowl and it was definitely a fine crack. I would need to examine it further and see how extensive it was and how deep it extended into the briar.

Jeff also captured a look at the left side of the bowl and it was definitely a fine crack. I would need to examine it further and see how extensive it was and how deep it extended into the briar. He took photos of the stamping on the sides of the shank. It is faint in spots but readable as noted above. In the first photo you can see the shank repair that has been done to the pipe. It is between the shape number 780 and the F/T stamp.

He took photos of the stamping on the sides of the shank. It is faint in spots but readable as noted above. In the first photo you can see the shank repair that has been done to the pipe. It is between the shape number 780 and the F/T stamp. I turned to Pipedia’s section on Dunhill Root Briar Pipes to get a bit of background on the Dunhill finishes (https://pipedia.org/wiki/Dunhill#Root_Briar). I quote:

I turned to Pipedia’s section on Dunhill Root Briar Pipes to get a bit of background on the Dunhill finishes (https://pipedia.org/wiki/Dunhill#Root_Briar). I quote:

Bruyere

The original finish produced (usually made using Calabrian briar), and a big part of developing and marketing the brand. It was the only finish from 1910 until 1917. A dark reddish-brown stain. Before the 1950s, there were three possible finishes for Dunhill pipes. The Bruyere was a smooth finish with a deep red stain, obtained through two coats, a brown understain followed by a deep red.

There was a link on the above site to a section specifically written regarding the Bruyere finish (https://pipedia.org/wiki/Dunhill_Bruyere). I turned there and have included the information from that short article below.

Initially, made from over century-old briar burls, classified by a “B” (denoted highest quality pipe); “DR” (denoted straight-grained) and an “A” (denoted first quality), until early 1915. After that, they became a high-end subset to the Dunhill ‘Bruyere’. The DR and B pipes, a limited production, they should be distinguished as hand-cut in London from burls as opposed to the Bruyere line which was generally finished from French turned bowls until 1917, when the Calabrian briar started to be used, but not completely. Only in 1920 Dunhill took the final step in its pipe making operation and began sourcing and cutting all of its own bowls, proudly announcing thereafter that “no French briar was employed”.

Bruyere pipes were usually made using Calabrian briar, a very dense and hardy briar that has a modest grain but does very well with the deep red stain.

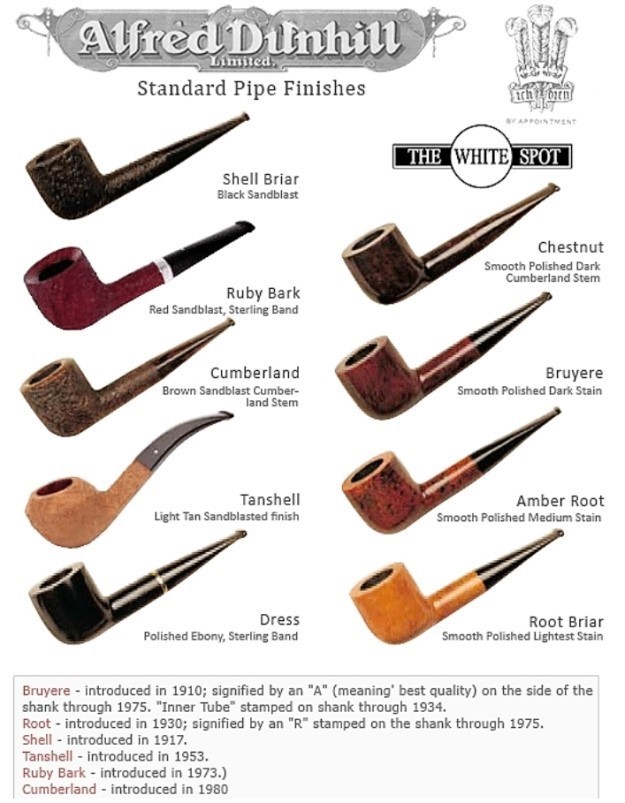

“Before the 1950s, there were three possible finishes for Dunhill pipes. The Bruyere was a smooth finish with a deep red stain, obtained through two coats, a brown understain followed by a deep red. The Shell finish was the original sandblast with a near-black stain (though the degree to which it is truly black has varied over the years). Lastly, the Root finish was smooth also but with a light brown finish. Early Dunhill used different briars with different stains, resulting in more distinct and identifiable creations… Over the years, to these traditional styles were added four new finishes: Cumberland, Dress, Chestnut and Amber Root, plus some now-defunct finishes, such as County, Russet and Red Bark.”

There was also a link to a catalogue page that gave examples and dates that the various finishes were introduced (https://pipedia.org/wiki/File:Dunnypipescatalog-1.png).  Armed with that information it was time to work on the pipe. I needed to examine the pipe more carefully at the shank repair and the potential cracks on the left side of the bowl. Lots to think about as I went to work on this bowl.

Armed with that information it was time to work on the pipe. I needed to examine the pipe more carefully at the shank repair and the potential cracks on the left side of the bowl. Lots to think about as I went to work on this bowl.

Jeff had reamed the bowl with a PipNet pipe reamer and followed up with a Savinelli Fitsall pipe knife to remove the remnants of cake. He scrubbed out the mortise and the airway in the shank and the stem with alcohol, cotton swabs, shank brushes and pipe cleaners. He scrubbed the exterior of the bowl, rim, shank and stem with a tooth brush and undiluted Murphy’s Oil Soap to remove the oils and tars on the rim and the grime on the finish of the bowl of the pipe. He rinsed it with running water. He dried it with a soft cloth. He was able to remove all of the debris in the briar leaving only the damage on the rim top and inner edge of the bowl. The small crack on the left side was clean and visible. I took photos of the pipe to show its condition before I started my work.

I took a close up photo of the rim top to show the condition of the top and edges of the rim. The top and the inner edges show some burn damage and nicks. The stem photos show the light tooth marks and scratching on the surface of the vulcanite.

I took a close up photo of the rim top to show the condition of the top and edges of the rim. The top and the inner edges show some burn damage and nicks. The stem photos show the light tooth marks and scratching on the surface of the vulcanite. I took photos of the stamping on the sides of the shank to capture the words if possible. It was faint as noted but could be read. I removed the stem and took a photo of the parts of the pipe to give a sense of the proportion of the parts to the whole. It is a well designed and made pipe.

I took photos of the stamping on the sides of the shank to capture the words if possible. It was faint as noted but could be read. I removed the stem and took a photo of the parts of the pipe to give a sense of the proportion of the parts to the whole. It is a well designed and made pipe. I decided to begin by addressing the damage on the rim top and the inner edge. I carefully sanded the edge with a folded piece of worn 220 grit sandpaper to smooth out the damaged areas and clean up the surface. I wanted to smooth out the damage and the darkening on the inner edge. It was a good start. More would need to be done before it was smooth enough to my liking.

I decided to begin by addressing the damage on the rim top and the inner edge. I carefully sanded the edge with a folded piece of worn 220 grit sandpaper to smooth out the damaged areas and clean up the surface. I wanted to smooth out the damage and the darkening on the inner edge. It was a good start. More would need to be done before it was smooth enough to my liking.  I examined the bowl to understand the depth and nature of the crack. I was surprised in some ways to see that there was not just the one crack that Jeff captured but there were a few small hairline cracks on both sides and the front and back of the bowl. The inside of the bowl and the rim top were crack free so I was dealing with surface cracks as far as I could see. It is just a guess, but I think that with the shank repair it appeared to me that the pipe was dropped and the cracks are pressure cracks that happened when the bowl broke loose from the shank and hit a hard surface. To further support this surmise the heel of the bowl had some road rash on it where it had hit a hard surface.

I examined the bowl to understand the depth and nature of the crack. I was surprised in some ways to see that there was not just the one crack that Jeff captured but there were a few small hairline cracks on both sides and the front and back of the bowl. The inside of the bowl and the rim top were crack free so I was dealing with surface cracks as far as I could see. It is just a guess, but I think that with the shank repair it appeared to me that the pipe was dropped and the cracks are pressure cracks that happened when the bowl broke loose from the shank and hit a hard surface. To further support this surmise the heel of the bowl had some road rash on it where it had hit a hard surface.

To give a sense of the nature and location of the cracks, I marked the thin hairline cracks (none go deep in the surface) with a black Sharpie pen. I took photos of the marks on the bowl. They go around the bowl almost all of them at the same horizontal position on the bowl sides. There were also two thin vertical cracks – one on the back and one on the front of the bowl all starting at the same height on the briar as the horizontal cracks but none going to the time edge or top. As noted there were road rash marks on the heel of the bowl. I marked the cracks with a black pen on the briar using a magnifier. They are all hairline cracks that seem to be in the surface.

I probed the cracks with a dental pick and found that they were only surface. None were deeper than the first one that Jeff pictured above. I filled them in with very thin CA glue so that it would seep into the cracks. I pressed it into the cracks with a dental pick tip. I set it aside to dry.

I probed the cracks with a dental pick and found that they were only surface. None were deeper than the first one that Jeff pictured above. I filled them in with very thin CA glue so that it would seep into the cracks. I pressed it into the cracks with a dental pick tip. I set it aside to dry.

Once the glue repairs cured I sanded the surface with 220 grit sandpaper to smooth them out and blend them into the surface of the bowl. They would be less visible and the repairs would be solid once I was finished.

Once the glue repairs cured I sanded the surface with 220 grit sandpaper to smooth them out and blend them into the surface of the bowl. They would be less visible and the repairs would be solid once I was finished.

I sanded the bowl with 320-3500 grit 2×2 inch sanding pads to further blend in the repairs, the rim top shaping and to smooth out the joint of the shank repair on the underside. I wiped the briar down after each sanding pad with a cloth and olive oil. The bowl began to take on a shine by the last sanding pad and the repairs are less visible.

I sanded the bowl with 320-3500 grit 2×2 inch sanding pads to further blend in the repairs, the rim top shaping and to smooth out the joint of the shank repair on the underside. I wiped the briar down after each sanding pad with a cloth and olive oil. The bowl began to take on a shine by the last sanding pad and the repairs are less visible.

I polished the briar with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding with 1500-12000 grit pads. I wiped the bowl down after each sanding pad to remove the sanding debris from the surface. It looked very good by the time I finished.

I polished the briar with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding with 1500-12000 grit pads. I wiped the bowl down after each sanding pad to remove the sanding debris from the surface. It looked very good by the time I finished.

I decided to de-ghost the bowl to remove the smell that was very present. I pressed cotton bolls into the bowl and used an ear syringe to fill it with alcohol. I plugged the shank end with another cotton boll and let it and it sit. The process would also serve as a way to check that the cracks did not go all the way from the bowl interior to the outside. If any did go through they would weep with alcohol and cotton balls in the bowl. The repaired cracks did not leak and once the cotton was removed the smell was gone.

I decided to de-ghost the bowl to remove the smell that was very present. I pressed cotton bolls into the bowl and used an ear syringe to fill it with alcohol. I plugged the shank end with another cotton boll and let it and it sit. The process would also serve as a way to check that the cracks did not go all the way from the bowl interior to the outside. If any did go through they would weep with alcohol and cotton balls in the bowl. The repaired cracks did not leak and once the cotton was removed the smell was gone.

I worked some Before & After Restoration Balm into the surface of the briar with my fingertips to clean, enliven and protect it. I let the balm sit for a little while and then buffed with a cotton cloth to raise the shine. The photos show the bowl at this point in the restoration process.

I worked some Before & After Restoration Balm into the surface of the briar with my fingertips to clean, enliven and protect it. I let the balm sit for a little while and then buffed with a cotton cloth to raise the shine. The photos show the bowl at this point in the restoration process.

With the bowl finished I set it aside and turned my attention to the stem. I sanded out the light tooth marks and chatter in the vulcanite with 220 grit sandpaper. It did no take to long to remove them all. It looked better.

With the bowl finished I set it aside and turned my attention to the stem. I sanded out the light tooth marks and chatter in the vulcanite with 220 grit sandpaper. It did no take to long to remove them all. It looked better. I further sanded it with 320-3500 grit 2×2 inch sanding pads and smoothed out the sanding marks further. I wiped it down after each sanding pad with an Obsidian Oil cloth to remove the sanding debris. It was looking very good by the last pad.

I further sanded it with 320-3500 grit 2×2 inch sanding pads and smoothed out the sanding marks further. I wiped it down after each sanding pad with an Obsidian Oil cloth to remove the sanding debris. It was looking very good by the last pad. I polished the stem with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding it with 1500-12000 grit pads. I wiped the stem down with Obsidian Oil after each pad. I polished it with some Before & After Pipe Polish – both Fine and Extra to deepen the shine. I wiped it down with a final coat of Obsidian Oil and set it aside to dry.

I polished the stem with micromesh sanding pads – dry sanding it with 1500-12000 grit pads. I wiped the stem down with Obsidian Oil after each pad. I polished it with some Before & After Pipe Polish – both Fine and Extra to deepen the shine. I wiped it down with a final coat of Obsidian Oil and set it aside to dry.

This Dunhill Bruyere 780F/T Group 4 Oval Shank Brandy is a surprisingly beautiful looking in spite of and probably because of the repairs. The red and brown stain on the bowl works well to highlight the grain. The polished black vulcanite taper stem adds to the mix. With the grime gone from the finish and the bowl it was a beauty and is eye-catching. I put the stem back on the bowl and buffed the pipe with Blue Diamond on the buffing wheel being careful to not buff the stamping. I gave the bowl and the stem multiple coats of carnauba wax on the buffing wheel and followed that by buffing it with a clean buffing pad. I hand buffed the pipe with a microfiber cloth to deepen the shine. The finished Dunhill Bruyere 780F/T Brandy is quite nice and feels great in the hand. Give the finished pipe a look in the photos below. I can only tell you that like the other pipes I am working that it is much prettier in person than the photos capture. The dimensions of the pipe are Length: 5 ½ inches, Height: 1 ¾ inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 ¼ inches, Chamber diameter: ¾ of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 34 grams/1.20 ounces. It will soon be added to the British Pipe Makers Section on the rebornpipes store.

This Dunhill Bruyere 780F/T Group 4 Oval Shank Brandy is a surprisingly beautiful looking in spite of and probably because of the repairs. The red and brown stain on the bowl works well to highlight the grain. The polished black vulcanite taper stem adds to the mix. With the grime gone from the finish and the bowl it was a beauty and is eye-catching. I put the stem back on the bowl and buffed the pipe with Blue Diamond on the buffing wheel being careful to not buff the stamping. I gave the bowl and the stem multiple coats of carnauba wax on the buffing wheel and followed that by buffing it with a clean buffing pad. I hand buffed the pipe with a microfiber cloth to deepen the shine. The finished Dunhill Bruyere 780F/T Brandy is quite nice and feels great in the hand. Give the finished pipe a look in the photos below. I can only tell you that like the other pipes I am working that it is much prettier in person than the photos capture. The dimensions of the pipe are Length: 5 ½ inches, Height: 1 ¾ inches, Outside diameter of the bowl: 1 ¼ inches, Chamber diameter: ¾ of an inch. The weight of the pipe is 34 grams/1.20 ounces. It will soon be added to the British Pipe Makers Section on the rebornpipes store.

As always, I encourage your questions and comments as you read the blog. Thanks to each of you who are reading this blog. Remember we are not pipe owners; we are pipe men and women who hold our pipes in trust until they pass on into the trust of those who follow us.