Blog by Jacek A. Rochacki

It is a pleasure to present this third article by Jacek Rochacki. In this article he is responding to a request that came up from several articles here on the blog about restoring Comoy’s pipes. In several of those pipes, particularly the Lumberman pipes, the stems were replacements. Jacek asked about putting the C logo on them. In this piece he gives the step by step procedure for inserting the C logo on a stem. Thank you Jacek for a helpful and timely article. It is greatly appreciated.

Let us begin from excerpt from A HISTORY OF COMOY’S AND A GUIDE TOWARD DATING THE PIPES, by Derek Green. It is published in Pipedia, unfortunately Derek’s internet pages do not exist anymore http://pipedia.org/index.php?title=A_History_Of_Comoy%27s_and_A_Guide_Toward_Dating_the_Pipes&action=edit

Inlaid “C”

“C” was first inlaid in the side of the mouthpiece around 1919. This was a complex inlay needing three drillings. First, a round white inlay was inserted, then the centre of the white was drilled out, and a smaller round black inlay was inserted. Finally, another drilling was made to remove the open part of the “C,” and an even smaller black inlay was inserted. This inlaid “C,” known as the “three-piece C,” was continued until the Cadogan era in the 1980s. However, the “C” in the 1920s and early 30s was much thinner and more delicate than the one post-war. Cadogan first changed the “C” to a single drilling with an inlay that had the “C” in the centre, and more recently it became a laser imprint. I have a cased pair of early 1920’ “Par Excellence” where the “C” is on top of the mouthpiece.

“Three piece C” originally published at the late Derek Green’s pages (sadly no longer existing today), the three elements are better visible here. Cracks on the letter “C” may be a subject for more detailed discussion; we remember such cracks in some old enameled objects, or in inlays of bone or ivory.

In order to follow this procedure the following essential tools are necessary:

– drill bit with sharp cutting edges of diameter corresponding with outer diameter of our “C” to be. I call it drill bit No. 1.

– drill bit with sharp cutting edges of diameter corresponding with inner diameter of our “C” to be. Let it be drill bit No. 2.

– drill bit with sharp cutting edges of diameter corresponding with diameter of this smaller black inlay that will remove the open part of the “C”. Let it be drill bit No. 3.

And: a jeweler’s frame saw, files, sandpapers, needle point marker, a drilling device possibly with regulation of rotation speed. Other tools like cutters, scraper, drills of other length and diameters may be of use. An old fashioned hand drill may be helpful because some operations on some materials should be performed at a very low speed.

First mark centre of our “C” to be. I do this using an ordinary needle fixed in a wooden handle but with tip slightly rounded. I heat the tip evenly with an ordinary lighter (I have been pipe smoker for years) and with this hot tip I mark a tiny hole, not deep, say, 0.2 mm. This centre mark will “guide” drill bit no.1. Just a few comments regarding drill bits: instead of using drill bits with ordinary/universal cutting edges shape there are other options that work well. Drill bits used in woodworking with “pilot” tip on them (brad point bits or dowelling bits) and Forstner bits of the correct diameter will work.

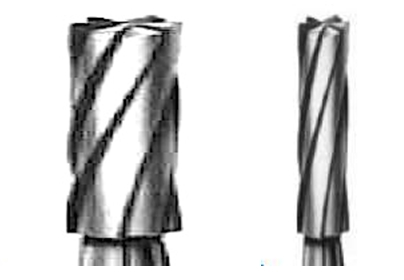

Another method would be to drill “preliminary” hole with a thin drill bit (say 1.2 – 2.0 mm) and then continue drilling with a cutter like the one below used by jewelers/stone setters for setting precious stones.

Yet another way of drilling the holes would be to use cylindrically shaped cutter after drilling the “preliminary” hole. This “preliminary” hole should be just a little smaller than the outside diameter of the “C” we are making. The diameter of our cylindrical cutter must be exactly the same diameter as that of the outside of our “C”.

When we say “drilling” we have an understood association with a drilling machine. While that is true, let us stop here for a moment. What is a drill bit? It is just a cutter of specific shape, normally used for making holes. If we agree that it is some kind of cutter, then drilling is one of numerous processes within category of machining. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Machining In our case we want to remove the material that we need in order to insert the “C” in a controlled way (subtractive manufacturing).

So the tool must be of proper shape and in best working condition = sharp! It would be going too far in this article to give a precise description on sharpening and maintenance of drills, but let us remember the necessity of using drill bits in best working condition. Basic information on drills including terminology is given on this site: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drill_bit#Twist_drill_bits

In some situations it is not necessary to operate drill bits or cutters with a drill/drilling device. If the bit is sharp and properly maintained etc., and we work with soft materials like vulcanite etc., it is sometimes OK to operate the drill bit with your fingers. The hole is created by drilling results from the sharpness and the right shape of cutting edges, not by using force. It is like carving with knife: the better and sharper the blade, the less force has to be employed.

When the hole is done/bored, we have to make the round white element to be inlaid. Ideally that would be a white vulcanite/material identical or well matching physical properties of the material of our stem, but I do not know if it is available today. Perhaps it might be found from this site: http://shop.hermanns.dk/group.asp?group=20

The best course would be to find a dealer who provides vulcanite in rods. If the diameter of the rod is bigger then what is needed, it is an easy job to thin it to our desired dimension by fixing a short piece in jaws of our drill (fixed in solid “horizontal stand) or in jaws that are fixed to our grinding/polishing machine, turn it on and while it turns use sandpaper to achieve required result. (I do not intend to convince all of us to begin learning simple turning – maybe we shall return to subject of turning vulcanite on another occasion, but a simple drill fixed in a horizontal stand, powered by electricity may serve as improvised lathe/turning machine!) .

When I had problems obtaining white vulcanite I remembered that it was available in acrylic. Acrylic is available in plates, rods, other forms. http://www.acrylite-shop.com/US/us/index.htm White opaque acrylic also works. If I had problems finding the required material in rods I use plates/sheets with a thickness of more than 3 mm. I cut the small disk of the required diameter with my trained, “sure” hand using a piercing saw or an even better idea would be to use a drill bit in the form of a short steel tube “crowned” with teeth, of inner diameter corresponding with diameter of the hole to be filled. It is the drill bit that reminds me of a hole saw bit without the “pilot” bit in the center.

At that time I was working and in constant touch with tool maker so I had my special tools custom made. But later in a distant place, in an improvised workshop, when I was in need of using such tool, I went to metal scrap and found a short piece of tube of hard metal of right diameter for my purpose. Steel would be good, but I learned that brass will also do because vulcanite and acrylic are soft materials. Using a jeweler’s triangular shaped needle file I made teeth, filed them to proper sharp cutting profiles and I had the “tube drill bit” that I need. Using this tool I was able to cut regular round elements.

These pictures give a better orientation to the shape of cutting top/“crown” so please, do not pay attention to the “body” of this tubular cutting tool. Sorry, I am far away from my own workshop and tools so I don’t have exact photos of tools that I write about.

When I had finished making the disk/”peg”/round filling element I glued it in the hole and the first part of the work was done.

And one more thing: acrylic is also available in form of powder that is offered with hardener and creates solid material. This technique came to be popular in artistic silver jewelry during ’70s. So this provides another option. You would fill our hole with white acrylic powder, use the hardening liquid and precisely fill up our hole. Attention: some of these materials are of an “aggressive” nature. They sort of “melt in” the “walls” of places to be filled, thus the circle does not have a clean straight line/border but the line/border will look “shadowed”. Keeping this in mind I suggest that you get all the necessary information from the manufacturer or competent dealer on how the “border” between the filling and “mother” material will end up.

Continuing this idea: There are so called cold enamels used in contemporary cheap jewelry or sometimes in repairing objects that were enameled. And other colored artificial materials, some of them are hardened with ultra violet rays. Information on these products can be found here http://www.gesswein.com/p-896-colorit-set.aspx The site may give some orientation regarding this matter.

When our “white large spot” is ready (of course after the filling is hardened or, if glued the glue has created a solid “binding” we have to level it up with files and sanding and buffing etc.) we find and mark the precise center and make another hole by drill bit of proper diameter that I call drill bit No. 2. Then make a black ebonite (or other material the identical color of the stem) “peg”, mini disk or other element for filling using one of techniques mentioned above. This should give you a nice inlay of a white circle on the stem. Then again it involves sanding, buffing etc. to make the surface smooth.

Then mark precisely the place on the right side of the inlaid circle for using drill bit No. 3. Drill the hole and with another very small diameter pin or disk, using one of techniques described above, we “open” the circle giving it the shape of letter C. Then after the final sanding, buffing etc. voila – our inlaid C should be ready.

—

But it is possible to approach the subject in a slightly different way. Let us return to the beginning when we were drilling larger hole by drill bit No. 1. Remember what I said above on “tube”, or “tubular drill bits”. There may be a way to find the tube of hard metal of diameters exactly matching inside and outside diameters of our “C” and of walls of thickness corresponding with thickness of our “C”. In old metalsmithing/goldsmithing/silversmithing/coppersmithing etc. metal handicraft workshops we made short tubes ourselves using so called draw plates and draw tongs or a simple hand powered machine named draw bench. I say this as curiosity, I am far from trying to convince us all to become goldsmiths/metalsmiths, but perhaps a goldsmith performing old style handicraft – if such still exists – would make short piece of tube of brass of requested dimensions. When we have our improvised, but ideal dimensioned “tube drill bit” it should be not too difficult to bore/”carve” the approximately +2 mm deep (of depth) circle of dimensions of our “C” to be. The groove should be filled with powered acrylic or, perhaps better (I mentioned about some “aggressive” acrylics in form of powder) an element made of solid white material.

I would proceed as follows: I would cut/make this white strip of width larger than the depth of the groove taking into consideration the fact that our grooved “O” is carved on a concave surface. The thickness of this white strip should be of width of our groove – the final thickness of the letter “C”. Then I would “soften” this strip with hot water, steam or a heat gun, so that I could form it by using jeweler’s pliers with round conical tips or using as sort of mandrel piece of metal wire of proper diameter. Bicycle or motorcycle spokes of different diameters make very useful mandrels of small diameters. Using these tools I would shape the white strip in the form of circle/ring fitting the carved circle groove and I would glue it in place. After leveling operations such as filling, sanding, buffing etc., I would make the opening of this “O” to make required “C” out of it as I described above.

It would be easier to find a tube of white appropriate material (acrylite) of dimension that is set/determined by our circular groove – maybe something like a cocktail straw – but I am aware that chances are small, so I mention it just for completing indication /description of possible ways of proceeding.

—

All this is OK from the technical point of view, but there is another aspect to consider. This is the aspect of the authenticity of signature or logo. When making copy of an original there are ways of “marking” the final product so that it is clear that our work is a copy and not a falsification. One of ways of such “marking” is to make a small change of dimensions in comparison to original. Here our wish of having a “clear conscience” meets the eventual problems of finding drill bits and materials in rods of dimensions that correspond exactly with dimensions of original “C” on Comoy’s pipes. I believe that this is one of situations where these two aspects meet and stay together in harmony.