Andrew Selking posted a refurbishment of a Heritage Heirloom Canadian and posted a copy of this brochure in his article. I wanted to also post the brochure separately for those who might be hunting for information on this remarkable brand from Kaywoodie. Thanks Andrew for finding this copy of the Heritage brochure. (Courtesy Kaywoodiemyfreeforum)

Category Archives: Pipe and Tobacco Historical Documents

Narrowing Down a Date for Kaufman Brothers & Bondy’s KBB and KB&B Pipes

Blog by Steve Laug

Over the years I have refurbished many older KBB and KB&B pipes. I have kept many of them and others I have passed on to other pipemen and women. The KBB and KB&B stamping on these old timers are stamped in a cloverleaf on the side or top of the shank of the briar pipes. In more recent years the KBB and KB&B stamping is no longer present. Kaufmann Brothers and Bondy was the oldest pipe company in the USA, established in 1851. The Club Logo predated Kaywoodie with the “KB&B” lettering stamped within the Club, and a multitude of KB&B lines were in production long before “Kaywoodie” first appeared in 1919. I have several of these old timers including a Borlum that was made before Kaywoodie became the flagship name for pipes from Kaufman Brothers & Bondy (KB&B). It was made before the Kaywoodie invention of the “Stinger” was added, and even before shank logos, model stamps and other features invented by Kaywoodie came to be standards of the pipe making industry. It comes from the time when names like Ambassador, Heatherby, Melrose, Suez, Rivoli, Cadillac and Kamello dominated the pre-Kaywoodie scene. Borlum is one of those vintage names. That information helps date pre-1919 KB&B pipes. There is still a long history following that for which I wanted further information. I was left wondering about the variations in the stampings on the Kaufmann Brothers and Bondy pipes. I had seen a pattern in that the Yello-Bole pipes made by Kaufmann Brothers and Bondy that were stamped without the ampersand (KBB) and other pipes made by them that had the ampersand (KB&B) and wondered about whether I had stumbled upon something. I had no idea why there was a variation in stamping. I decided to do some digging online to see if I could get more information regarding this variation. The purpose of this article is to collate what I found in order to provide some guidelines on dating the older pipes and to differentiate between the two stampings.

I was left wondering about the variations in the stampings on the Kaufmann Brothers and Bondy pipes. I had seen a pattern in that the Yello-Bole pipes made by Kaufmann Brothers and Bondy that were stamped without the ampersand (KBB) and other pipes made by them that had the ampersand (KB&B) and wondered about whether I had stumbled upon something. I had no idea why there was a variation in stamping. I decided to do some digging online to see if I could get more information regarding this variation. The purpose of this article is to collate what I found in order to provide some guidelines on dating the older pipes and to differentiate between the two stampings.

In the past when I had questions about KB&B pipes, Yello-Bole pipes and KW pipes I have found that the Kaywoodie Forum http://kaywoodie.myfreeforum.org/ftopic13-0-asc-0.php has been an invaluable source of information on the brand. The information found there on the KBB and KB&B pipes is very useful. Dave Whitney has an article on the topic of KBB pipes. I will summarize what I have found there to help with my search. I have several older Yello-Bole pipes with the shovel drinkless mechanism and the KBB-in-a-clover logo on the left side of the shank (not KB&B). These also have the yellow circle on the stem.

In the past when I had questions about KB&B pipes, Yello-Bole pipes and KW pipes I have found that the Kaywoodie Forum http://kaywoodie.myfreeforum.org/ftopic13-0-asc-0.php has been an invaluable source of information on the brand. The information found there on the KBB and KB&B pipes is very useful. Dave Whitney has an article on the topic of KBB pipes. I will summarize what I have found there to help with my search. I have several older Yello-Bole pipes with the shovel drinkless mechanism and the KBB-in-a-clover logo on the left side of the shank (not KB&B). These also have the yellow circle on the stem. From what I can ascertain from Dave’s information, pipes with this configuration seem to have been produced between the years of 1938-42. The lack of the aluminum stem ring and the drinkless mechanism that came out in the later period of KBB history 1945-50 (World War II) point to the earlier period. The shape/style of the drinkless mechanism helps to date the pipe. Let’s summarize what we know so far. The Kaywoodie stamp appeared in 1919 thus any pipes with the KB&B in a cloverleaf stamped on the shank pointed to a pre-1919 pipe. From 1919-1938 the combination of the KBB stamping and the shovel mechanism in the tenon help date those pipes. The metal drinkless attachment came out in 1945 and following. I have KB&B pipes and KBB Yello-Bole pipes from this early era.

From what I can ascertain from Dave’s information, pipes with this configuration seem to have been produced between the years of 1938-42. The lack of the aluminum stem ring and the drinkless mechanism that came out in the later period of KBB history 1945-50 (World War II) point to the earlier period. The shape/style of the drinkless mechanism helps to date the pipe. Let’s summarize what we know so far. The Kaywoodie stamp appeared in 1919 thus any pipes with the KB&B in a cloverleaf stamped on the shank pointed to a pre-1919 pipe. From 1919-1938 the combination of the KBB stamping and the shovel mechanism in the tenon help date those pipes. The metal drinkless attachment came out in 1945 and following. I have KB&B pipes and KBB Yello-Bole pipes from this early era.

Reading further led me to ascertain that the KBB in a cloverleaf stamp dates a pipe back to the ’30’s. I also learned that the 4 digit shape numbers stamped on the right side of the shank are older than 2 digit ones. The pipes with the logo inlaid on top of the stem are older than ones that have it on the side. I learned that in the past, Kaufman Brothers and Bondy would sort shipments of briar and send the culls to be used for Yello-Boles, meaning they got some quality briar. One fellow on the web believes that is why Yello-Bole pipes tend to be smaller over all, working around flaws. He also said that he thinks calling these pipes Kaywoodie seconds is a bit of a misnomer, being that Kaywoodie was one of the largest briar purchasers in the world at the time (’20’s-50’s) and got some fantastic wood.

Armed with this bit of information on the brand I did some more research and came across the SM Frank website http://www.smfrankcoinc.com/home/?page_id=2. There I found a wealth of historical information on Kaywoodies, Yello-Boles and the merger between KBB and SM Frank and later Demuth. It was a great read and I would encourage others to give the website a read. The information in the next paragraph was condensed from that site. I found confirmation for the statement above that the Yello-Bole line was an outlet for lower grade briar not used in Kaywoodie production. Yello-Bole’s were introduced in 1932 and manufactured by Penacook, New Hampshire subsidiary, The New England Briar Pipe Company. Advertising from the 1940′s, pictures the Yello-Bole “Honey Girl” and urges the pipe smoker to smoke the pipe with “a little honey in every bowl.” Honey was an ingredient of the material used to line the inside of the bowl. It was said to provide a faster, sweeter break-in of the pipe.

I went hunting further to see if I could find information on establishing dates for Yello-Bole pipes and found that there was not a lot of information other than what I had found above. Then I came across this link to the Kaywoodie Forum: http://kaywoodie.myfreeforum.org/archive/dating-yello-bole-pipes__o_t__t_86.html I quote the information I found there as it gives the only information that I found in my hunt to this point.

“OK so there isn’t a lot of dating information for Yello-Bole pipes but here is what I have learned so far.

– If it has the KBB stamped in the clover leaf it was made 1955 or earlier as they stopped the stamping after being acquired by S.M. Frank.

– From 1933-1936 they were stamped Honey Cured Briar.

– Pipes stems stamped with the propeller logo they were made in the 30s or 40s no propellers were used after the 40s.

– Yello-Bole also used a 4 digit code stamped on the pipe in the 30s.

– If the pipe had the Yello-Bole circle stamped on the shank it was made in the 30s this stopped after 1939.

– If the pipe was stamped BRUYERE rather than briar it was made in the 30s.

The pipes with propeller logos appear to be made in the 1930’s or 1940’s. The pipe with the yellow circle logo imprinted into the shank of the briar was made in the 1930’s. Those with the brass O seem also to have been made in the 1930’s.

The pipes with propeller logos appear to be made in the 1930’s or 1940’s. The pipe with the yellow circle logo imprinted into the shank of the briar was made in the 1930’s. Those with the brass O seem also to have been made in the 1930’s.

One further item was also found on that site. It was just a passing comment in the midst of some information on Kaywoodie pipes. I quote: “The pre-Kaywoodie KB&B pipes were marked on the shank with a cloverleaf around KB&B. Some early Kaywoodies had this same marking on the shank, but the practice was dropped sometime prior to 1936. Yello-Boles also had KBB in the leaf on the shanks, but did not have the ampersand found on Kaywoodies.” (Highlighting is mine)

That is all the information I have gathered to date. I don’t have anything on the multitude of stem stampings or any other age indicators. In summary, it seems that the stem logos, the stamping on the shanks of KBB and KB&B, the type of stinger apparatus in the tenon as well as aluminum decorative trim all are a part of dating the KBB and KB&B pipes. From the final paragraph above I have the answer to my question on the difference in the ampersand or lack of it – until 1936 the KBB and KB&B in a cloverleaf were stamped on the shanks of pipes made by Kaufman Brothers and Bondy. After 1936 that stamping disappeared and was replaced with the various Yello-Bole and Kaywoodie designation stampings. If anyone has more definitive information or other methods of determining date please feel free to post it in the comments below and I will add them to this piece.

If you would like to have a look at the KBB pipes that I have restored do a search on the blog for Kaufmann Brothers & Bondy, KBB, Yello-Bole and Kaywoodie pipes. The search will bring up quite a few of the pipes that I and other contributors to the blog have posted here.

ADDENDUM

I received two photos of the stinger apparatus that Andrew Selking removed from the KBB Doc Watson that he wrote about here. I am including them here. We both think that they predate the shovel like apparatus that I picture above.

A Collection of Brigham Documents

Blog by Bill Tonge & Steve Laug

Bill Tonge, who has written several blogs for rebornpipes has become a big collector and fan of Brigham pipes. He refurbishes them and enjoys their workmanship. Several months ago he talked with Brian Levine, the US Brigham representative and received these brochures and sales flyers for Brigham pipes. When he told me about the collection I asked him to photograph them for me so that I could post them on the blog. What follows is that collection. The text is hard to read in some of the brochures but the photos of the shapes and designs are amazing. There are shapes in there that I have never seen and I have had a lot of Brigham pipes over the years. Enjoy the photos. Thanks Bill for photographing these for us to read. Much appreciated.

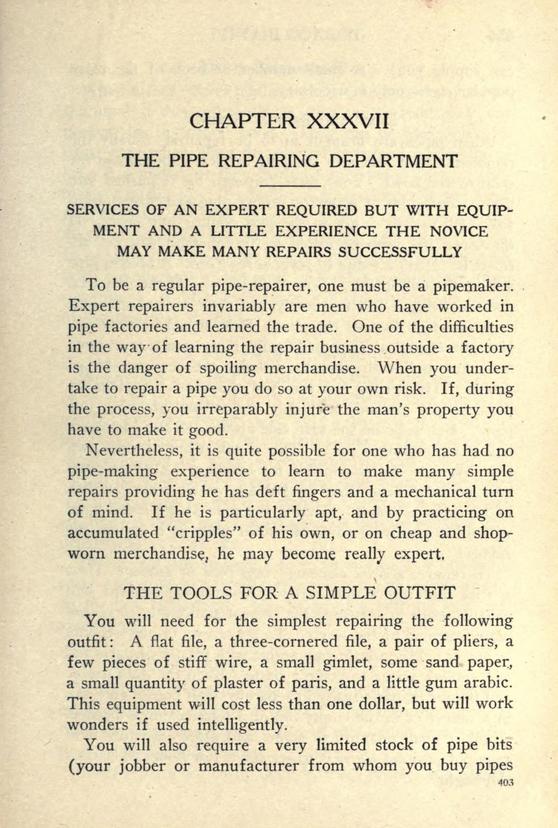

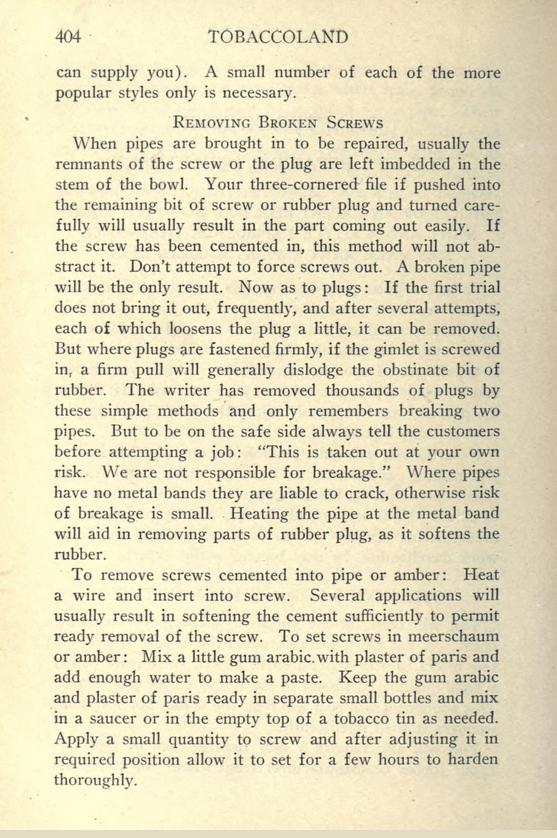

Tobaccoland, Chapter 37 the Pipe Repairing Department – by Carl Avery Werner

Blog by Chris Chopin and Steve Laug

Chris Chopin, a reader of and writer for rebornpipes sent me a link to an old chapter on pipe repair that he thought I would enjoy reading. He was right, I love it. It is a chapter from the book Tobaccoland, by Carl Avery Werner. It is Chapter 37 and is entitled “The Pipe Repairing Department”. It is a great read and well worth taking the time to reflect on if you are one who, like me, loves to repair and bring old pipes back to life. I wanted to pass it on to all of you who read the blog so I converted the entirety of the chapter into photos so that I could post the pages on the blog for you to read. If you would like to read it in PDF format click on the link below and download it in that format http://library.albany.edu/preservati…rt7_chpt37.pdf.

As usual with me, one thing leads to another and I wanted to read more of Werner’s book. Having read the chapter on pipe repair I was intrigued enough to do some digging to see if I could find the book as a whole. I wanted to read more of Werner’s Tobaccoland and see if the rest of it was as enjoyable and entertaining. I was able to find the following link to a full online version of the book https://archive.org/stream/tobaccolandbooka00wernuoft#page/n9/mode/2up.

As usual with me, one thing leads to another and I wanted to read more of Werner’s book. Having read the chapter on pipe repair I was intrigued enough to do some digging to see if I could find the book as a whole. I wanted to read more of Werner’s Tobaccoland and see if the rest of it was as enjoyable and entertaining. I was able to find the following link to a full online version of the book https://archive.org/stream/tobaccolandbooka00wernuoft#page/n9/mode/2up.

Some Interesting Notes on Jobey Pipes – Chris Chopin

Blog by Chris Chopin

Chris emailed me this piece while I was traveling and thought I would be interested in it. He was correct. Chris seems to dig up some interesting information when he goes on the information hunt. Thanks Chris.

Chris emailed me this piece while I was traveling and thought I would be interested in it. He was correct. Chris seems to dig up some interesting information when he goes on the information hunt. Thanks Chris.

Very interesting pipe! I’ve never seen a Jobey without the link. Apologies in advance for the wall of text to follow, I’m a Jobey fan.

Immediate thought is that it must be made before 1969, which I believe is when Wally Frank got the patent on the Link. Before that, the Jobey Company is a bit of a fun mystery. They made pipes, as Pipedia will tell you here: http://pipedia.org/wiki/Jobey for a lot of different companies but the origins seem to be shrouded in mystery, and most people claim that the origins were in England, followed by American production, and then a later move to St. Claude. I think that’s wrong. Jobey’s Brooklyn Briar is present at least as of ’69. That’s where they patented the Link, that’s where the roots are.

There’s not a lot of chatter about it, but if you can lay your hands on a copy of “The Tobacco World”, Volume 61, from 1941, there is a brief mention that reads “Norwalk Pipe Expands” and in the body states that Norwalk Pipe Corporation, “manufacturers of Jobey and Shellmoor pipes”, is moving to larger offices at 218 East Twenty-Sixth Street, NYC, as announced by Louis Jobey, president of that company. Norwalk is listed as one of the alternate distributors for Jobey on Pipedia, but without mention of Louis actually working there at the time.

Before that, the first mention of Jobey seems to be back in 1915, when two guys named Ulysses and Louis Jobey of Brooklyn, New York had a neat patent for an odd sort of cavalierish pipe in 1915, here’s the link: http://www.google.com/patents/USD46998

But less than four years later, in 1918, there’s a notice in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on November 6th to the effect that Louis Jobey declared bankruptcy in the District Court, with final hearing scheduled for December 1918. And in an even sadder turn, that same month sees a funeral notice for Lorraine Jobey, the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Louis Jobey, formerly of Brooklyn but now living in Moline Illinois at the home of Mr. and Mrs. George E. Hutchinson. The little girl evidently died in a fall.

I never found anything else on Ulysses Jobey except that he evidently had a “junior” after his name or a son by the same name. Because Ulysses Jobey, Jr. was listed as the vice president in New Jersey of Lakewood Pipe Company Inc., a maker of smoker’s articles, in the 1922 New York Co-partnership and Corporation Directory for Brooklyn. Given the timing I’m guessing Ulysses, Jr. was the brother.

Now this is just too much Brooklyn to be coincidence, so here’s my take on the real Jobey history. I think the company was started by two brothers in Brooklyn in the teens with a new idea for a pipe, and failed amidst terrible tragedy. I think one brother went to one company and another to the other, but it was Louis who continued making Jobey pipes through the 40s under that name, despite (I am guessing) no longer owning the company. And I think it was the Norwalk Company that was bought out by Wally Frank in the pre-link days. To my mind it’s always been American.

Now again, there’s a lot of speculation here. But I think it’s leaving too much to coincidence to read the history of Jobey without mention of those two brothers, I think they’re the actual Jobeys. Sorry for the wall of text, hope this was interesting and not excessive, lol.

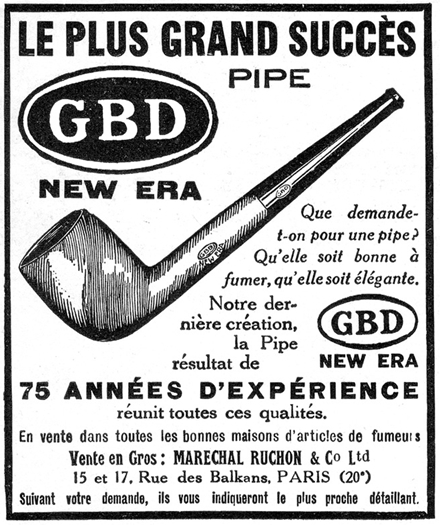

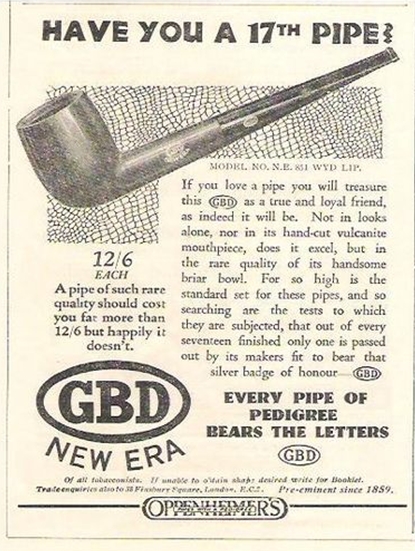

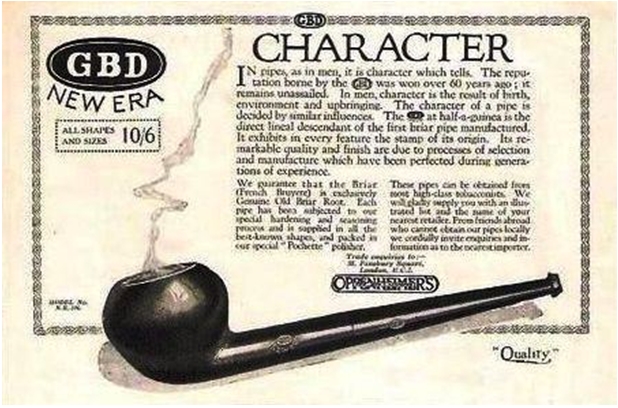

Finding Out Who Created GBD – Story of a Pipe Brand – Jacques Cole

I have had this article by Jacques Cole saved on my hard drive for a long time now. I have read it many times but last evening I read it again and thought it would be good to put on the blog. It gives a concise history of the brand and the mergers that went on to bring the brand to what it is today.It is a quick read for the GBD pipe collector and lover. This is the kind of information I am always on the lookout for because of the historical connection it gives to the pipes I smoke, collect and refurbish. It was printed in TOBACCO July 1982, pp.16-17. I formatted it to fit in a Word document, added some photos of old advertisements and done minor editing in terms of punctuation. – Editor

A number of pipe brands owe their introduction and continuation to craftsmen who gave the family name to their product and were followed for several generations by their descendants.

GBD however was not quite the same. The founders did give their names, but the ‘family’ was a partnership of men of similar skills and equal purpose of mind. They created a brand which became strong enough to gather its own momentum. The creators were no doubt wise to choose initials rather than one of their names.

Who were these creators? Ganneval, Bondier and Donninger were three ‘Master Pipemakers’ who got together in Paris in 1850 to manufacture meerschaum pipes. It was a bold decision as these were troubled times in France. Charles Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte has returned after the 1848 revolution and become President of the Republic. Following a coup d’etat in 1851, he made himself Emperor Napoleon III in 1852. He was incidentally a keen pipesmoker and may well have owned one or more early GBDs.

Ganneval is a known, if not common name in the Saint-Claude district of France and he seems to have been a native of these parts, where he learnt his craft. The name Bondier is still found in Saint-Claude, but may originally have come from Paris. One Bondier is known to have fled from Paris during the 1789 Revolution and settled in Geneva. Some of his descendants returned home eventually via Saint-Claude where our Bondier worked in the local industry learning the skills of the wood-turners and making stems for the clay and porcelain pipe industries. Donninger was probably of Swiss or Austrian origin, having gained experience in Vienna, the home of meerschaum pipes.

Of the three founders, Bondier was to survive 30 years longer than the others, but new partners took their places. The official name of the firm also changed, showing a succession of partners: Bondier Ulnch & Cie, then Bine Marechal & Cie and finally A Marechal Ruchon & Cie. Auguste Marechal and Ferdinand Ruchon saw the firm into the 20th century, their name being used as a company for well over 50 years.  The intention of the creators of GBD was to make meerschaum pipes. Details of their early production is scarce, but they made carved heads,‘simpler’ models which included a fair proportion of bents of traditional meerschaum style, and similar shapes to the then familiar clay pipes, which we would recognise as Dublins or Belges, with a sprinkling of early Bulldogs.

The intention of the creators of GBD was to make meerschaum pipes. Details of their early production is scarce, but they made carved heads,‘simpler’ models which included a fair proportion of bents of traditional meerschaum style, and similar shapes to the then familiar clay pipes, which we would recognise as Dublins or Belges, with a sprinkling of early Bulldogs.

The founders had early registered their mark and were able to fight off any infringement. A proof of the rapid growth and importance of the brand is shown by the findings of the Court of Chancery in London in 1874 in favour of GBD against someone using the name illegally. Many other ‘cases’ were won by GBD in various countries.

GBD understood at once the advantage of briar when this was discovered in the 1850s to be an ideal material for pipe making. The close contacts already established with the industry in Saint-Claude helped to provide the raw material. While briar helped the simplification of pipe shapes, meerschaum production went hand in hand with briar and we can see in surviving carved briar pipes the influence of Vienna that came with Donninger. Briar soon became the main material.

MEDAL AWARDS

Business and reputation developed quickly and there is no better indication of this than the record of 15 medal awards gained at international exhibitions in nine cities all over the world during the first 40 years of GBD.

The partners must have been busy: they show the brand establishing itself in Europe, the USA, Canada and Australia. South Africa was to come later.

At the start of the ‘briar age’, GBD used only the best quality although after a time a second slightly lower quality became necessary to meet rapidly growing demand.

The need for a wider price range was solved by the variety of fittings. Amber, horn, ivory and even quill were used for mouthpieces, followed by vulcanite towards the end of the 1870s. Various types of silver and gold bands were greatly in demand and so were pipes in fitted cases, plain or carved.

FINE COLLECTION

GBD was offering towards the end of the century 1500 ‘models’, bearing in mind that a shape offered with three different mouthpieces was listed as three different models. This made a really fine collection. A shape chart of 1886 shows a basic 125 shapes (the actual total was 1600 which included 12 Billiards, 36 Bents and 46 Dublins/Belges) many with heels. These formed the core of the collection shown in Amsterdam in 1888. One of the principal features of GBDs was the slimness of their stems.Some 20 years later, the balance had somewhat changed: still 36 Bents;

Billiards gaining in popularity (36); 32 Dublins/Zulus, a few still with heels; but the Belge, cousin to the clay pipe, down to two small models.

On the other hand Bulldogs had risen to 15 shapes. In the first ten years of this century, amber and amberoid were still used, but vulcanite and horn mouthpieces were the most popular mouthpieces. Another ‘trend’ was the inclusion of some 30 models in various shapes fitted with

‘Army Mounts’. The range had by now taken on a more British aspect,and for good reasons: GBD had become British.

Charles Oppenheimer had started his successful General Merchant business as an import-export house in 1860. He was joined by his brothers David and Adolphe and brother-in-law Louis Adler. Briar pipes were among the earliest lines handled and the connection with GBD Paris started in 1870, being most important customers. A. Oppenheimer & Co were appointed exclusive agents in 1897. Adolphe Oppenheimer took a keen interest in the pipe side of the business, and most important, James Adler, son of Louis, was to take a major part in the ‘change of nationality’.  With other interests in Saint-Claude, Oppenheimer acquired A. Marechal Ruchon & Cie, in 1902 and it became A Marechal Ruchon & Co. Ltd., a British company with four directors, two British and two French, namely, Adolphe Oppenheimer and James Adler in London, and Auguste Marechal and Ferdinand Ruchon in Paris, with the latter as the first chairman of the new company.

With other interests in Saint-Claude, Oppenheimer acquired A. Marechal Ruchon & Cie, in 1902 and it became A Marechal Ruchon & Co. Ltd., a British company with four directors, two British and two French, namely, Adolphe Oppenheimer and James Adler in London, and Auguste Marechal and Ferdinand Ruchon in Paris, with the latter as the first chairman of the new company.

FAMILY INVOLVED

The Adler family is still very much involved with GBD. The head office was in London with the main, now enlarged factory in the Rue des Balkans. Paris, while a large factory was being built in Saint-Claude. Although perhaps envisaged at that stage, manufacturing in London did not get underway until the 1914/18 War when it is recorded that in 1916, the bowl turning facilities in Saint-Claude shipped some 27,000 dozen bowls to GBD Paris of which 18,000 dozen went to the London Works. After the War, GBD production continued in both London and Paris. London Made went mainly to the then British Empire and the USA, while Paris supplied the French and

European markets. Later the products of both countries were to be seen on occasion side by side, particularly to satisfy special requirements.

The siting of factories has a bearing on our story, so we must jump ahead a little to record that in 1952, the manufacture of French GBDs was transferred from Paris to Saint-Claude, together with all services, to the benefit as it turned out of GBDs on the French market in particular.  We have seen that early Briar GBDs were made in only one, later two qualities and the need to mark the difference did not arise. There were few finishes but towards the end of the 19th century demand was changing, for instance the UK had a “penchant” for the darker finishes.

We have seen that early Briar GBDs were made in only one, later two qualities and the need to mark the difference did not arise. There were few finishes but towards the end of the 19th century demand was changing, for instance the UK had a “penchant” for the darker finishes.

Qualities were therefore sub-divided and we see the introduction of the GBD XTRA (note the spelling). The GBD Speciales were as the name implied, special models, finishes and fittings. GBD XTRAs were the cream, being mostly straight grains. The ‘ordinary’ quality was simply stamped GBD.

Demand after the First World War called for further identification starting with GBD ‘London Made’ which became ‘Standard London Made’, followed by GBD ‘New Era’, top of the range in 1931 at 12/6d! GBD ‘Pedigree’, although first thought of around 1926, was well established in the late 1930s. GBD ‘New Standard’ was created to give a boost to the ‘Standards’ of the 1920s and a newly introduced sandblast was called GBD ‘Prehistoric’, still bearing a small GBD ‘Xtra’ stamp.  French made GBDs followed more or less the same ideas; still however using ‘Xtra’ and ‘Speciale’ while in the late ’20s a metal system GBD was introduced under the name GBD ‘Extra Dry’.

French made GBDs followed more or less the same ideas; still however using ‘Xtra’ and ‘Speciale’ while in the late ’20s a metal system GBD was introduced under the name GBD ‘Extra Dry’.

The 1920s also saw an important development with the introduction of the metal GBD inlay on mouthpieces which gave the pipes that extra ‘touch of class’. This inlay has been used on GBDs for nearly 60 years.

After the closing of the Paris factory, GBD ‘Standard’ was used on a basic fine range with an appropriate finish to fill the lower price range. Both the London and the St Claude factories continued to supply top quality ‘Straight Grains’ and cased pipes were still in demand up to the

1950s. In the 1960s the Jamieson shapes from London equaled or even headed the best in the very specialised field of handmade pipes.

GBD of course, keeps up with the times, and while the steady ‘Pedigrees’ and ‘Standards’ keep going, the need for innovation has produced a new series: GBD ‘Gold Bark’ fitted with a gold ‘bark’ band, GBD ‘Jetstream’ with a modern mouthpiece design, and GBD ‘Champagne’ with a high quality acrylic mouthpiece.

We cannot leave GBD without mention of an important line just below the GBD quality — often referred to on the French market as the ‘petite’ GBD — the ‘City de Luxe’ range first registered in 1922. The distinctive metal star on the mouthpiece was introduced at the same time as the GBD inlay. ‘Citys’ are made in both London and France.  STRONG POSITION

STRONG POSITION

GBD is in a strong position on the world’s markets and is known to all discriminating pipesmokers. The families now involved with its success are the Oppenheimers and the Adlers of London. It was the late Alan Adler who coined the phrase ‘having the Holy Fire’ which sums up the feeling in the GBD organisation, his son John being head of the firm.

Older readers will remember Jack Cole, who left London in 1919 for a’short stay’ in France but went on to remain there up until his death over 50 years later, and for a time had his sons with him. They and the many others who have contributed to the GBD story have a great affection for the brand. Back in 1850, Ganneval, Bondier, and Donninger really started something.

Gold & Silver Hallmarks On Pipes – Alan Chestnutt

I receive Alan’s newsletter from reborn briar and also follow his blog so I read what he has written with expectation that I will learn something new and so far I have never been disappointed. (You can access his blog by clicking here.) Often he clarifies things for me that I have long believed to be true but have not done enough research on or thinking about to make conclusions. In the case of this blog post Alan has given us a very useful tool on interpreting hallmarks in the gold of silver work on pipes. I have used many of the sites that Alan has linked but never seen them in one place like this. I wrote Alan and asked if I could post it here on rebornpipes. He responded that he would be glad to have it posted here. Thanks Alan for doing the hard work for us and giving us access to what you have learned.

I receive Alan’s newsletter from reborn briar and also follow his blog so I read what he has written with expectation that I will learn something new and so far I have never been disappointed. (You can access his blog by clicking here.) Often he clarifies things for me that I have long believed to be true but have not done enough research on or thinking about to make conclusions. In the case of this blog post Alan has given us a very useful tool on interpreting hallmarks in the gold of silver work on pipes. I have used many of the sites that Alan has linked but never seen them in one place like this. I wrote Alan and asked if I could post it here on rebornpipes. He responded that he would be glad to have it posted here. Thanks Alan for doing the hard work for us and giving us access to what you have learned.

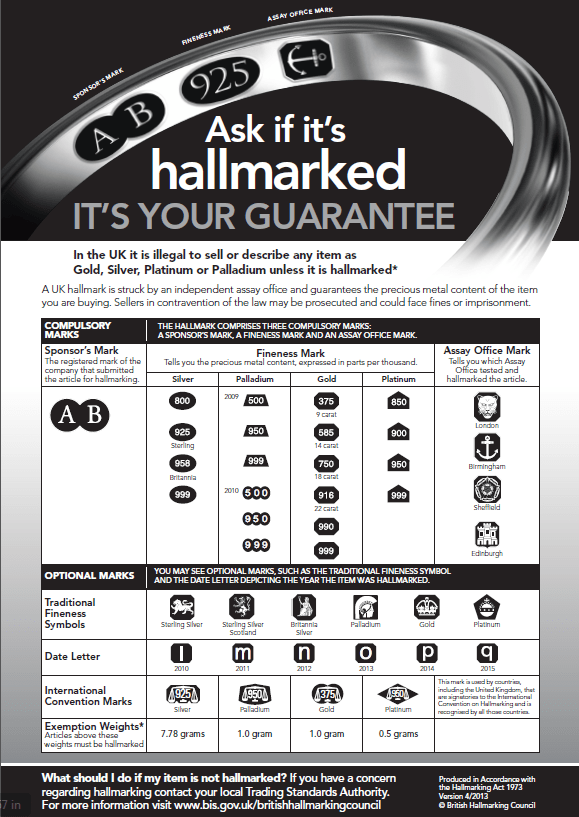

Hallmarks have been around in the UK for over 800 years. They were originally introduced by a law in 1300 to protect the public from being defrauded into being sold an item not made of the purity of the precious metal that was being advertised. Hallmarking is a legal requirement in the UK as well as in many other countries, mostly in Europe. The countries in which it is a requirement have formed a Convention of hallmarking, and if the item has been hallmarked in one of the Convention countries, then it is officially recognised in any other Convention country. Many countries do not have any hallmarking requirements, the USA being one. But what exactly is hallmarking?

Background to Hallmarking

Hallmarking is the guarantee that an item of precious metal has been officially assay tested. It is a legal requirement that any item of precious metal in the UK is officially hallmarked before it is offered for sale. If no hallmarks exist then it is unlawful to describe an item as silver, gold or platinum and the item can only be referred to as white or yellow metal. The relevant Act of parliament governing hallmarks in the UK today is The Hallmarking Act 1973 which states:

Prohibited descriptionsof unhallmarked articles.

(1)Subject to the provisions of this Act, any person who, in the course of a trade or business –

(a) applies to an unhallmarked article a description indicating that it is wholly or partly made of gold, silver or platinum, or

(b) supplies, or offers to supply, an unhallmarked article to which such a description is applied, shall be guilty of an offence.

The process of hallmarking means that every single item of precious metal has to be sent to an officially recognized Assay Office which is a member of the British Hallmarking Council. There were a number of these around the UK in the past, though some have now closed and the remaining offices are London, Birmingham, Sheffield and Edinburgh (plus Dublin in the Republic of Ireland – relevant for hallmarking of Peterson pipes).

In the Assay Office, a sample of the metal is scraped from an inconspicuous part of the item. This sample is then chemically tested to verify its purity of precious metal. Items are hardly ever made purely of the precious metal alone (bullion excepted). They are normally alloys with other metals or contain other impurities. The standard for Sterling Silver is 925 which means that 925 parts in every thousand are pure silver. Purity of gold items vary from 9k gold (375 parts per 1000), 14k (585), 18k (750), 22k (916) up to 24k (999) which is virtually pure gold. Once the purity of the precious metal has been confirmed by the Assay Office, they hallmark the item accordingly, which is the symbol of guarantee.

Hallmarks consist of at least 4 symbols. The largest of the symbols is usually at the top and is normally referred to as the maker’s mark (read the term maker’s mark loosely as will be explained later). This is followed underneath by 3 further symbols which represent:

1. The official symbol for the Assay office which carried out the testing.

2. The symbol for the purity of the precious metal.

3. A symbol which represents the year in which the test was carried out.

In more recent times an additional symbol has been introduced which is internationally used and recognised throughout the Convention countries to symbolise the purity, which consists of a set of scales with the purity value written below (e.g. 925 for silver).

Hallmarks on Pipes

Hallmarking on the silver and gold decorations of pipes allow us certain advantages. They can be used in (most) cases to establish who made the pipe and when it was made. I state (most) cases as there are certain anomalies that we must take account of. We must remember that it is only the silver which needs to be hallmarked and this need not be (and in 99% of the cases would not have been) already applied to the pipe. It has been said in the past that some Peterson pipes have a silver collar with a date stamp which precedes the introduction of a certain series of designs. On others, the date mark on a silver collar does not match that of the date mark on a silver rim. This most likely occurs by Peterson sending off a large batch of silver collars to the Dublin Assay Office to be tested and hallmarked, which then sit in the factory until they are fitted to a pipe sometime later. In these instances it is more accurate to use the introduction date of that series of pipes than the date letter on the official hallmark. Or in the case of a mismatch of dates between a collar and a rim to use the later date mark. Why would this happen? It is a simple case of economics of scale. There can sometimes be anomalies in the maker’s mark too.

The “Maker’s” Mark

I stated above to read the term “maker’s mark” loosely. It was called this in the past, but as the law relates to the sale of these items, the legal liability for hallmarking ultimately lies with the retailer. This is an important issue to remember. The mark is officially called the Sponsor’s Mark and is referred to in the Act as such:

3 Sponsors’ marks.

(1)Before an article is submitted to an assay office to be struck with the approved hallmarks there shall be struck on the article a mark indicative of the manufacturer or sponsor and known as the sponsor’s mark:

Provided that the assay office and the manufacturer or sponsor of an article may make arrangements for the sponsor’s mark to be struck by that assay office upon submission of the article to be struck with the approved hallmarks.

Every sponsor’s mark in the UK is unique. It is made up of three elements:

1. the shape surrounding the mark (or shield)

2. the string of letters or initials

3. the font used in the letters

The combination of these three elements will make a unique mark for every sponsor. Before an item can be hallmarked, the sponsor must first register their sponsor’s mark with the assay office they wish to use.

My knowledge of hallmarking comes from being involved in jewellery retailing. A number of years ago, my partner and I sold jewellery items online. We imported the items from abroad. They did not have any UK hallmarks on the items, and before we could sell the items as being gold, we had to have them hallmarked. We have a sponsor’s mark registered with the Birmingham Assay Office which comprises of the initials TD in Arial font inside a lozenge shaped shield.

My knowledge of hallmarking comes from being involved in jewellery retailing. A number of years ago, my partner and I sold jewellery items online. We imported the items from abroad. They did not have any UK hallmarks on the items, and before we could sell the items as being gold, we had to have them hallmarked. We have a sponsor’s mark registered with the Birmingham Assay Office which comprises of the initials TD in Arial font inside a lozenge shaped shield.

Registering a sponsor’s mark is an expensive business. Firstly you must design a mark which must be unique to be accepted by the The British Hallmarking Council. Then you have the actual cost of registration. Then you must have a metal stamp made to stamp the items. As shown in the above extract from the Act, we had an arrangement with the assay office to hold our stamp on our behalf so that they could stamp the items with our mark whilst hallmarking, so I have never actually ever seen or held it. This involves a further fee. Even though most hallmarking today is carried out using a laser etching service, it is still a legal requirement to have an official metal stamp made!

Large jewellery companies in the UK like H. Samuel and Beaverbrooks do not make their own jewellery. Yet all the jewellery in their stores bears their own mark. This makes perfect sense. If an item is imported, the original maker will never have a registered mark in the UK to begin with, so the task must be undertaken by the retailer to comply with the law. So how does all this relate to pipes?

Confusion Surrounding Hallmarks

Hallmarks are not definitive and can lead to confusion in certain cases. I have already pointed out above some of the confusion surrounding dates. The sponsor’s mark can in certain circumstances lead to even greater confusion as to who actually mad e a particular pipe.

e a particular pipe.

I was prompted to write this article while I was selling this 1910 Bewlay pipe, which I described as possibly being made by Barling, who were the largest supplier to Bewlay at the time. I received a message from a respected Barling authority – someone who I have the utmost respect for and who has helped me on many occasions. He said that the pipe in question could not be a Barling pipe as it did not have the EB.WB hallmark. He told me that he actually owned a Bewlay pipe from 1900 made by Barling. The shank was stamped Bewlay, but the silver band was hallmarked with the EB.WB hallmark. He rightly pointed out that other manufacturers also made pipes for Bewlay and that he could not quite make out the “maker’s mark”, which might show who actually manufactured the pipe.

I will digress for a moment. As I have my own registered sponsored mark, I could send off a pipe to the assay office to have the silver band hallmarked. However, the cost of sending over a single pipe to be hallmarked is likely to be around £30, which would be more than the value of the silver in the band to begin with. It therefore wouldn’t make economic sense. The cost would be made up of the following:

1. posting the pipe to the assay office

2. a “checking in” fee

3. a “per item” fee for the actual testing and hallmarking.

4. a “checking out” fee

5. The cost applied by the assay office for return shipping which must be fully insured (read expensive!)

The least expensive of these fees is the actual hallmarking fee! It therefore makes sense to send a large number of items to the assay office at the same time to spread out the overall cost of the other ancillary fees – especially for silver items. Obviously Barling as a manufacturer could take advantage of this economy of scale.

Barling made pipes for many pipe retailers around the country. They would in most cases (sometimes exclusively) stamp the shank with the name of the retailer, while the silver band retained the EB.WB stamp which allows us to distinguish them today as a Barling made pipe. So why was this? It was not the case that it was Barling’s responsibility to hallmark the bands. It was simply the case that most pipe retailers were single outlet businesses and the simple economy of scale would mean that it was cost prohibitive for the small retailer to register his own mark and they were happy that the manufacturer had taken the responsibility.

Back to the pipe in question, I already knew what the sponsor’s mark was on this pipe. It was B&Co which was the registered sponsor’s mark for Bewlay& Co. This obviously didn’t help distinguish who made the pipe. Other companies who supplied Bewlay like Loewe and Charatan also had their own hallmarking arrangements, so why was this stamped as B&Co?

At the time, the House of Bewlay was the largest tobacconist and pipe retailer in the UK. It had many outlets all over the country. So why did a retailer who could have bought in all their pipes already hallmarked want to register their own mark? To many small retailers the hallmarking of a few pipes would have been expensive and an administrative burden. But to Bewlay’s, who had the economies of scale, the answer is simple. Having your own mark brought about a symbol of prestige and proprietorship. Not only could the shanks of their pipes be stamped exclusively with their own name, but now the silver bands could be too. I can imagine the minutes of a meeting between Bewlay and the pipe manufacturer’s proceeding as follows:

Managing Director of Bewlay – “From now on, we would like you to supply all your pipes without hallmarking the silver band” (thinking…prestige and ownership).

Managing Director of Pipe Company: (thinking Bewlay is their largest single customer!) “Certainly Sir!” (… also thinking about cost reductions due to the headache of hallmarking being removed)

This though does not explain the 1900 Bewlay pipe which has the silver band hallmarked by Barling themselves. A little investigation into this reveals the most likely answer. Although Bewlay was officially founded in London in 1780 it was not until the early 20th century that it saw its major expansion, having been bought by Imperial Tobacco Company. Imperial also acquired the Salmon &Gluckstein retail empire in 1902 which at that time was the largest tobacconist in the country. Hence a ready made retail network of stores which were re-branded as House of Bewlay in 1902.The sponsor’s mark B&Co was not registered until 1903, hence the 1900 pipe still retaining the Barling hallmark.

In conclusion, the presence of the B&Co sponsor’s mark means we cannot definitively say that the pipe was made by Barling. Likewise we cannot definitively say that it was not! We therefore have to rely on experience of the look and feel of the pipe against what the other manufacturers were producing around that time, and rely upon a best guess analysis.

Hard Rubber and other Early Plastic Used In Pipes – Ronald J. de Haan

While searching the web for information on Bakelite I came across this very interesting article on vulcanite, Bakelite and Casein that were all used at some point in history in making pipes and pipe stems. The link for the article, that includes the photos used to illustrate the various pipes are included is shown below: http://pipeacademy.org/pdf/publications/AIP%20Publication%20PDFS/2001%20Pipe%20Year%20Book,%20de%20Haan%20searchable.pdf

I have edited the article and posted it here without the photos that were used in the original piece. I have not found this concise a description of the materials anywhere else. Thank you Ronald J. de Haan for your excellent research.

This article is an attempt to draw attention to a very interesting field within the area of smoking collectibles. Many collectors of tobacco articles know something about many smoking accessories made out of synthetic material, like ashtrays, match-holders and cigar-cases.

In general though, there is very little knowledge about pipes made out of synthetic material, like hard rubber and other early plastics. Pipes (bowl and stem) that are completely made out of synthetic material are quite rare. This is not surprising, because synthetic material is less heat resistant during smoking, than traditional materials such as meerschaum, clay or briar.

The use of hard rubber for the production of pipes did not come as the result of long research; but is the result of the discovery of vulcanisation in 1839, which increased the applications for rubber enormously.

The introduction of rubber

Rubber is a natural product extracted from the rubber tree, Hevea brasiliensis. The bark of the tree is cut in a controlled way, as not to disrupt the flow of sap so the tree will survive. The milk-like, syrupy substance is known under several names. In the Amazon area the inland name for rubber tree is Cahucha (weeping tree). This word lives on in the French Caoutchouc and the German Kautschuk, both meaning rubber. The name rubber dates from the mid 18th century and was introduced by the famous British theologian and scientist Joseph Priestly.

The story of rubber in the western world begins at the end of the 15th century. On his second journey to America, Christopher Columbus visited the island of Haiti and saw children playing with elastic balls. The material was introduced in Europe as a toy. For the next centuries its application was limited.

In 1731 the French Charles de la Condamine, during a surveyor-expedition in Peru discovered that the local inhabitants used rubber to make their clothing waterproof. They also made shoes and bottles by pulling the material around moulds and letting the rubber harden in the sun or above a fireplace.

The British Thomas Hancock experimented in 1820 with forming rubber by mechanical power after heating the material, which resulted in the first waterproof rain clothes, made by Charles Mackintosh. It was the American Charles Goodyear who patented in 1839 the process of stabilising rubber with the help of sulfur, which is called the vulcanization process.

The vulcanization process

By vulcanising the rubber for a longer time and by adding a larger percentage of sulfur (up to 50%) the product became harder. The result was a new material. It was the first half synthetic plastic made out of a natural product changed by a controlled chemical process.

This new material is known by several names, depending on the production or the appearance: ebonite, because it looks like ebony; vulcanite because of the process of heating, referring to the Roman god Vulcan; hard rubber, which speaks for itself.

One of the first patents by Goodyear states that the new material was used in the production of pipe stems, an application that proved to be very suitable because the material was easy to mould. This hard rubber, though not the most suitable material for pipe-bowls, was used for the production of complete pipes until the 20th century, undoubtedly because of the ease of doing the detailed work. In order to prevent the bowls from melting or burning away, it was necessary to place inserts of meerschaum, briar or clay in the bowl of the tobacco pipe. Cigar and cigarette holders however, were produced without an insert because it was not necessary.

Two other synthetic materials have to be mentioned in this article, because they have been used extensively in the production of pipes, sometimes in combination with hard rubber. These two materials are casein and Bakelite.

Casein

Casein, in full casein-formaldehyde, consists as the name suggests of an important part of the milk protein. Casein can be extracted from skimmed milk with a specific enzyme. By exposing the kneadable doughy substance to the liquid formaldehyde for days or even weeks a new material emerges, which will not melt, even at high temperatures.

It is a so-called thermosetting synthetic material, like rubber (semi-synthetic). The patent for the production of this material dates from 1899 and belonged to the Germans Krische and Spitteler. They called the new material Galalith. Later it became known also as Erinoid, Ameroid and Kasolid. Casein can be coloured easily. A drawback of the material is its sensitiveness to liquid. Long-term exposure to liquid makes the material crack.

The pipe-making industry used the material widely till after the Second World War for the production of cigarette pipes (pipettes), as it could easily be pierced, turned or modeled. The long Charleston cigarette pipes of the 1920’s are made of casein.

Bakelite

Bakelite, officially phenol-formaldehyde, is regarded as the first fully synthetic material. The Belgian born Leo Baekeland invented it in the United States. He succeeded in controlling the long known heavy chemical reaction between phenol and formaldehyde. Controlled high temperature and high-pressure, formed the basis for his patent which he obtained in 1907. The result of the chemical reaction is an amber-coloured resin. Mixed with filling material like sawdust, asbestos or textile fibres the result, after pressing, is a hard thermosetting synthetic material. The most important qualities of this material are its insulation for electricity, its solidity and the possibility of use in mass production.

These qualities made Bakelite the most successful synthetic material in the first half of the 20th century. From 1928 it was also produced as moulded resin. Both the pressed and the moulded forms were suitable for the pipe making industry. Pipes were made from Bakelite and moulded phenol-resin. Complete pipes of Bakelite are very rare because of its lack of heat resistance. Phenol-resin however was frequently used for pipe mouthpieces and cigarette holders because it imitated amber.

Literature

Cool, Patrick and Sessor, Catherine, Bakeliet, Helmond 1993

Engelen, Jos, De Meerschuimpijp, in: Pijpologische Kring Nederland, 20″c jaargang nr, 80 (1988), page 998

Katz, Sylvia, Early Plastics, Shire Publication nr, 168 (1986)

Perree, Rob, Bakelite, Amsterdam 1996

Tymstra, Fred, Bakelieten pijpen met stenen potje, in: Pijpelogische Kring Nederland, 16° jaargang nr, 63, page 566-572 (1993)

Woshner, Mike, India-Rubber and Gutta Percha in the Civil War Era, z.pl., z.j.

Catalogues

Smokers Articles and Walking Canes and Miscellaneous Goods, The Novelty Rubber Co., New York 1877

Price Current, Goodyear’s Rubber MFG Co. And Goodyear’s I.R. Clove MFG Co., New York 1880

Pipes and smokers Articles, Zorn & Co

George, Philadelpia 1892 (reprint by Paul Jung Jr., 1989)

Catalogue General, Bessard-Pignol Gustave, Clermont Ferrand 1894

With special thanks to:

Richard Schoevaart, Amsterdam, Karelloeff, Laren, Jacques Bergmans, Weert.

A Peterson Dating Guide; a Rule of Thumb – Mike Leverette

Blog by Mike Leverette

As a pipe refurbisher who has worked on and restored many older Peterson pipes over the years and a researcher who likes to understand the brands of pipes I work on I have always been amazed at how little there is on the history of the brand. When I was working on one of the first Peterson pipes that came my way I remember writing then calling Mike Leverette and seeking his help in dating the little Pre-Republic pipe I had in hand. Mike directed me to this article of his on Pipelore.net and later sent me a copy of the piece he had written. It became my go to piece when seeking information on Petersons. Mike and some of his colleagues created the well-known ‘Peterson Pipe Project’ web site. Mike died in 2009, following a long battle with cancer. His work has been taken up by Mark Irwin and Gary Malmberg who are currently working on a book on entitled, The History of the Kapp & Peterson Company and their system pipes. According to the Briar Books Press website the book’s release has been pushed back to Christmas 2015. While we all wait for the publication of this work I am posting the article that Mike sent me many years ago now and dedicate it respectfully to my good friend Mike’s memory. Without further ado here is Mike’s article.

This guide first appeared in pipelore.net on August 26, 2006 by: Mike Leverette.

Introduction

The history of Ireland is an old and honourable one; steeped in warfare, family, racial and religious traditions. No other country can compete in comparison. However, the first couple of millennia of Irish history have no relevance to this dating guide. Should you wish to read more on the history of the Irish, I recommend “The Story of the Irish Race” by Seamus MacManus who gives a very vivid, and near as we can tell an accurate portrayal of their history.

History pertinent to our purposes began in the year 1865; the year Charles Peterson opened a small tobacco shop in Dublin. Later in 1875, Charles Peterson approached the Kapp brothers, Fredrich and Heinrich, with a new pipe design and with this, a very long-lived partnership was formed, Kapp & Peterson. This new pipe design is the now famous Peterson Patented System Smoking Pipe. By 1890, Kapp & Peterson was the most respected pipe and tobacco manufacturer in Ireland and rapidly gaining followers in England and America. In 1898 another of Peterson’s remarkable inventions became available, the Peterson-Lip (P-Lip) mouthpiece, also known as the Steck mouthpiece. So for the purpose of this dating guide, we will study Irish history, relevant to our pipe dating needs, from 1870s until now.

Before we start with this Peterson dating guide, an observation; the Kapp Brothers were making pipes as early as the 1850s and in many of the shapes we now associate with Peterson since the Kapp Brothers simply took their existing shapes and incorporated Charles Peterson’ s patented design into them. From their inception, Kapp & Peterson’s goal was to make a good smoking pipe that the ordinary, common working man could afford and we believe they have, very admirably, lived up to this.

Explanation of Title

The vagaries of Peterson’s processes do not allow for an accurate dating guide so this guide is a ‘rule-of-thumb’ guide only. For example; Peterson did not take up the old Country of Manufacture stamps as new ones were issued so depending on which one the various workers happen to pick up, the stamps can and do cross over the boundaries of the various Eras. Some of the pipes of the Sherlock Holmes Series of the 1980s have pre-Republic stamps, as well as other pipes produced in 2000. However, there will not be too many of these missed stamped pipes. For silver anomalies, see the section on silver marks.

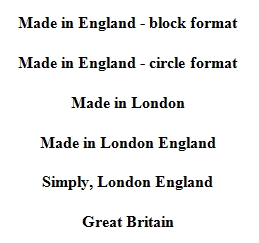

Stamping of Bowls

During the years of Kapp and Peterson’s business operations, the country of Ireland has undergone several name changes and K&P’s stamping on their pipes reflects these changes. Knowing these changes, a Peterson pipe can be roughly dated and placed in “eras.”

• The Patent Era was between the years of K&P’s formation until the expiration of the patent; 1875 through approximately 1910. Though for our purposes we will list this era as 1875 through 1922. Peterson pipes made during the majority of this period had no “Country of Manufacture” (COM) stamped on them. However, later in this period, say around 1915/16, Peterson began stamping their pipes “Made in Ireland” in a block format.

• The Irish Free State was formed on 15 January 1922. So the Free State Era will be from 1922 through 1937. Peterson followed with a COM stamp of “Irish Free State” in either one or two lines, either parallel or perpendicular to the shanks axis and extremely close to the stem.

• Eire was formed on 29 December 1937. The Made in Eire Era will be from 1938 through roughly 1940? or 1941?. For dates with ?’s, see below. Peterson now stamped their pipes with “Made in Eire” in a circle format with “Made” and “Eire” in a circle with the “in” located in the center of the circle. This COM was used during the years of 1938 – 1940?/41?. Later they stamped their pipes with “Made in Ireland” in a circle format (1945?-1947?) and still later with “Made in Ireland” in a block format (1947?-1949). The “Made in Ireland” block format came in either one line or two lines.

• The Republic Era is from 1949 until the present. The Republic of Ireland was formed on 17 April 1949. From 1949 to present the stamp for this era is “Made in the Republic of Ireland” in a block format generally in three lines but two lines have been used with or without Republic being abbreviated.

• English made Peterson pipes actually spans between the pre-Republic and Republic eras. In 1895, Peterson opened a shop in London England that lasted until the late 1950s or early 1960s. So the English Era, for a simplified date, will be from 1895 through 1959. The stamps Peterson used in London and that we have seen are:

Though there are a couple of more, the above will give one the general idea. We believe the earliest stamp of this era was the “Made in England” in a block format since Peterson was using the “Made in Ireland” block format at about the same time on their Irish production pipes. The “Made in England” circle format was used during the same time frame as the “Made in Eire” and “Made in Ireland” circle formats.

As one can see this is pretty straightforward but there have been inconsistencies within this method of stamping. Peterson was never very energetic in removing their old stamps from the work stations so the older stamps can and did cross-over into the newer Era’s.

The explanation for the question marks in the 1940’s dates is, during the Second World War briar was hard to come by for obvious reasons, so no one can say for sure what years Peterson produced briar pipes and how many briar pipes were produced in those years. Why the switch from “Made in Eire” to “Made in Ireland” is anyone’s guess since the country was still technically Eire until 1949. As a point of interest and due to the shortage of briar, Peterson did make clay and Bog Oak pipes during the war years though they had ceased clay pipe production in the Patent Era and Bog Oak production back in the early 1930s.

The “Made in Ireland” block format (above) can be another headache in dating Peterson pipes since this stamp was used in the late Patent Era as well as the late 1940s. So for a guide we must take into consideration the style of lettering Peterson used on their pipes. From the start of the Patent Era until somewhere in the early 1930s, Peterson used the “Old Style” lettering that used a forked tail “P” in Peterson.

The “Made in Ireland” block format (above) can be another headache in dating Peterson pipes since this stamp was used in the late Patent Era as well as the late 1940s. So for a guide we must take into consideration the style of lettering Peterson used on their pipes. From the start of the Patent Era until somewhere in the early 1930s, Peterson used the “Old Style” lettering that used a forked tail “P” in Peterson.

From then until now, Peterson used the more familiar script “P” (above) intermixed with a plain block letter “P.” Later in the 1970s, Peterson began production of “commemorative” pipes, often referred to as “replica” or “retro” pipes and these will also have the old style lettering but according to the pipes that we own and have seen, most of these will have a small difference in the original forked tail “P”. Again, there appears to be a cross-over with the old style forked tail and the later forked tail P’s (below). However, these commemorative pipes generally have a silver band with hallmarks so one can date these pipes by the hallmark.

From then until now, Peterson used the more familiar script “P” (above) intermixed with a plain block letter “P.” Later in the 1970s, Peterson began production of “commemorative” pipes, often referred to as “replica” or “retro” pipes and these will also have the old style lettering but according to the pipes that we own and have seen, most of these will have a small difference in the original forked tail “P”. Again, there appears to be a cross-over with the old style forked tail and the later forked tail P’s (below). However, these commemorative pipes generally have a silver band with hallmarks so one can date these pipes by the hallmark.

Also, we must address the stamp “A Peterson Product.” During the last few years of the Pre-Republic era and throughout the Republic era, Peterson began stamping their other lines, such as Shamrocks and Killarneys, with “A Peterson Product” over the COM stamp. So a pipe stamped thusly will have been made say from 1948 to the present with the COM stamp identifying it as a pre-Republic or a Republic pipe.

Also, we must address the stamp “A Peterson Product.” During the last few years of the Pre-Republic era and throughout the Republic era, Peterson began stamping their other lines, such as Shamrocks and Killarneys, with “A Peterson Product” over the COM stamp. So a pipe stamped thusly will have been made say from 1948 to the present with the COM stamp identifying it as a pre-Republic or a Republic pipe.

Silver Band Dating

Silver hallmarks are placed on the silver after an assay office, in Peterson’s case, the Dublin Assay Office, has verified that the silver content is indeed sterling, in other words 925 parts of silver per 1000 parts of the metal. The silver hallmarks on Peterson pipes are a group of three marks, each in an escutcheon; the first is a seated Hibernia denoting Dublin Ireland, the second is a harp denoting the silver fineness, and the third is a letter denoting the year. The style of letter and the shape of the escutcheon the letter is in, will determine the year in which the assay office stamped the metal band and not necessarily the year the pipe was made. Peterson orders these bands by the thousands and sends them to the assay office for hallmarking. The assay office will stamp the date of the year in which they received the bands and it may be a year or two or three before Peterson’s employees happen to place one of these bands on a pipe though generally the bands are placed on a pipe in the year they were stamped. The Dublin hallmarks can be found in any book on silver markings or on one of several web sites.

For the one year, 1987, the Dublin Assay Office added a fourth mark to commemorate the City of Dublin’s founding in 988. However, the Peterson pipes we have and have seen with silver dates of 1987 and 1988 generally do not have this fourth mark.

Here again, we must add a “maybe” to the above hallmarks. On 1 June 1976, certain countries attended an international conference on silver markings and decided to adopt an entirely different mark for sterling silver. This mark is an Arabian numeral, 925, located between the scales of a balance beam and in Peterson’s case may or may not have the Hibernia and Harp marks to either side. These particular pipes can only be said to date between 1976 and the present, and were stamped as such for shipment to the different countries involved in the conference. For pipes shipped to all other countries, Peterson still uses the old style hallmarks. Peterson pipes with a sterling silver band that does not have hallmarks could have been made for the United States market since the United States only requires sterling silver to be stamped “sterling silver” or “sterling.”

Before we close this section on silver hallmarks, we must address the marks that many people refer to as hallmarks. Peterson uses three marks on some of their pipes that are not silver hallmarks but are rather another Peterson logo (below). These marks are:

• A Shamrock for the many shamrocks found in Ireland

• A Prone Fox representing the famous fox hunts in Ireland’s history, and

• A Stone Tower for the many hundreds of stone towers spotted throughout Ireland

Again these are not genuine silver hallmarks:  Also many of the newer pipe smokers think that Kapp & Peterson’s official logo of “K&P,” each in a shield shaped escutcheon, are hallmarks but, of course, they are not. They are simply Kapp & Peterson’s initials.

Also many of the newer pipe smokers think that Kapp & Peterson’s official logo of “K&P,” each in a shield shaped escutcheon, are hallmarks but, of course, they are not. They are simply Kapp & Peterson’s initials.

Dating by Series

Dating by series or numbers is an area in which we are having a difficult time of establishing. For instance, the 300 series are all shapes used during the Patent Era and we believe Peterson started using this number system when the original patent expired. In the case of the 300 series and without looking at the COM stamp or silver hallmark, one can only say that they were made between 1910 and today. The 300 series was not in Peterson’s 1905 catalogue.

Though we are still trying to find the start dates of many series, here are some that we are pretty positive about:

• Centennial Edition – 1975 (for K&P’s Centennial)

• Great Explorers Series – 2002

• Harp Series – 2002

• Mark Twain Numbered Edition – 1979 (numbered 1 through 400)

• Mark Twain 2nd Numbered Edition – 1981 (numbered 1 through 1000) Mark Twain Un-numbered Edition – 1983 to c1989 (There must be a fourth production of Mark Twain pipes for there a couple of men who own Mark Twain pipes with a silver date of 1998; we are still trying to pin down the dates of this fourth production.)

• Emerald – c1985 to 2003

• Millennium Edition – 1988 (for the City of Dublin’s founding)

• Sherlock Holmes Series – 1987 to c1989

• Return of Sherlock Holmes Series – c1991

• Sherlock Holmes Meerschaums – 2006

Peterson Clay, Bog Oak and Cherry Wood Pipes

Peterson Clay, Bog Oak and Cherry Wood pipes were offered in the Patent Era with or without a formed case, as also offered with their briar and meerschaum pipes.

Peterson made clay pipes during the Patent Era with only two shapes being offered and depicted in their 1905 catalogue. During this period their clay pipes were stamped/moulded “Peterson Patent” and could be purchased with either a silver or nickel band. How long and in what years Peterson made these clays is not known but as stated above two shapes were offered in their 1905 catalogue. Then during World War II, Peterson again made clay pipes due to the understandable shortage of briar. The clays of this period are stamped “Peterson System” and were only offered with nickel bands. This later production of clay pipes ended with the closing of Peterson’s London Shop in the late 1950s or early 1960s.

Also during World War II, Peterson again made bog oak pipes and again, this was due to the shortage of briar. They had previously ceased production of bog oak pipes in the 1930s during the Irish Free State Era. On the subject of bog oak pipes, Peterson’s bog oaks will always have a metal band with either amber (early production only) or vulcanite stems and will have the appropriate COM stamp. As with their clay pipes, Peterson offered a silver or nickel band on their early bog oak pipes of the Patent Era and just a nickel band on their WWII bog oak pipes.

Peterson made pipes of cherry wood during their Patent Era in both the smooth finish and the bark-left-on finish; and as with their clay pipes, Peterson used both amber and vulcanite stems and choice of silver or nickel bands. And like their clay pipes of the Patent Era, the introduction and termination dates are not known. Peterson Cherry Wood pipes were offered with or without a meerschaum lining.

Metal Ferrules of Military Mounted Pipes

As pipes get older, wear will, with all the handling, cleaning and polishing, take its toll on the nomenclature which will eventually disappear, thus, making it harder to determine the age of your Peterson. A good thorough cleaning of old hand oils, dirt and ash will sometimes bring out a faint outline of the nomenclature but sometimes the nomenclature has completely worn away and even this cleaning will not bring it back. So where do we go from here to determine the pipe’s age? The shape of the metal ferrule on Peterson pipes with the military mount will give you some hint though not a precise date.

During the Patent Era, the metal ferrules of Peterson military mounts will have a more ‘acorn-ish’ shape, that is, the bend will have a larger radius as it turns down to meet the stem. This larger radius gradually (?) changes to a smaller radius, more abrupt bend, during the Irish Free State Era and even more abruptly after World War Two when the bend takes on the modern day shape.

The metal ferrules on Peterson clay pipes during the Patent Era are angular while their clay pipes of World War Two will have the bend shape as do most of the Peterson pipes from then until now.

As with everything pertaining to the dating of Peterson pipes, this method can only give us a hint to the age of the pipe but it is better than nothing at all. The years of these changes in the metal ferrule shape are, we are sure, lost to the ages. However, someone with a larger number of Peterson pipes than we may be able to check the silver dates for more precise age boundaries. Well, this is a very short dating guide and we hope that you will be able to date more accurately your favourite Peterson with this information.

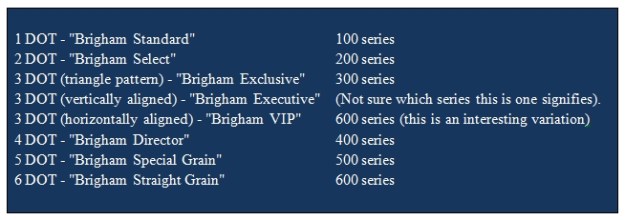

Interpreting the Stampings on Brigham Pipes

I have received quite a few emails and tweets over the years about how to read the stamping on Brigham pipes. I have hunted for information in the past and almost always had to do more digging than should have been necessary. So yesterday when I was asked again to help with the stamping on a particular pipe I did some digging. The friend who asked said the stamping was 5955 on the underside of the shank. He said he had called Brigham and that they had told him that number was not on their shape charts. He had hit a dead-end. We connect on Twitter so he contacted me and asked for help. I thought I would give it a try to see what I could find out about the pipe. I Googled and read various online pipe forums where information was given. I searched for Brigham shape and numbering charts and old catalogues. Nothing helped. Then I decided to go to the Brigham site itself and go through the layers of information there and see what I could dig up. I was certain the clue to the mystery had to be there. It was just a matter of spending the time reading through the layers of information there to see what could be found.

I have received quite a few emails and tweets over the years about how to read the stamping on Brigham pipes. I have hunted for information in the past and almost always had to do more digging than should have been necessary. So yesterday when I was asked again to help with the stamping on a particular pipe I did some digging. The friend who asked said the stamping was 5955 on the underside of the shank. He said he had called Brigham and that they had told him that number was not on their shape charts. He had hit a dead-end. We connect on Twitter so he contacted me and asked for help. I thought I would give it a try to see what I could find out about the pipe. I Googled and read various online pipe forums where information was given. I searched for Brigham shape and numbering charts and old catalogues. Nothing helped. Then I decided to go to the Brigham site itself and go through the layers of information there and see what I could dig up. I was certain the clue to the mystery had to be there. It was just a matter of spending the time reading through the layers of information there to see what could be found.

The Brigham Pipes website is found at http://www.brighampipes.com. I read through a lot of the pages on the site and took notes as I read. I have edited the material I found and organized it here in one place so it would be easy to use in the future. I am thankful to Brigham for putting this information on the site because it certainly made identifying the pipe my friend wrote me about quite simple once I had read through the information on the website and in the various blog posts I found.

I have many older Brigham Pipes in my collection as do many of you who read this blog. The information I have collated will be useful to more people than me and the person who sent me the question. I have collected older Brigham pipes for over 15 years and enjoy smoking them with and without their patented maple filter system. Brigham pipes were made in Canada for nearly 100 years, though I am told that recently they are made in Italy and finished in Canada. There have been variations in the stamping on the pipes over the course of the years and I have most of the variations in my collection. However, the one constant has been has been the 3 digit stamping code on the underside or the side of the shank. The pipes are organized in several groups designated from the 100 series to the 700 series (100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700). The quality of the pipes goes up as the series numbers rise. The 100 series pipes are entry-level pipes and each level above that increases in quality and price. The 700 series is made of the highest quality of briar and workmanship.

Using this information I took the number that was given to me – 5955 stamped on the bottom of the pipe’s shank – as my starting place. The first number in the stamp denoted the series (1 to 7). Thus the pipe was a 500 series pipe. The next 2 numbers indicated the shape number which in this case was 95. I am assuming that is the shape number for the Zulu or yachtsman shape of this pipe. Summarizing what I had learned so far – I now knew what the first three digits in the stamping meant. The “595” indicated a 500 series pipe in shape #95. Reading further I found that a letter could follow the numbers in the stamp – particularly on older pipes. The letter indicated the size of the bowl. Thus the letter S = small, M = medium, ML = medium/large, L = large. I wrote the questioner and asked him to magnify the stamping on his pipe. Sure enough, the pipe was a 595S – the final stamp was the letter S, making this pipe a 500 series Zulu with a Small bowl. Mystery solved on this one. Armed with this information I went through my older Brigham pipes and was able to interpret all of the stamping.

I knew from previous research and refurbishing these pipes that Brigham utilized a dot system to denote the pipe series. Brass pins were inserted on the side or top of the stem in dot patterns and these were what I looked for to ascertain that I had an original stem on a Brigham pipe that I had found in a thrift shop, antique mall or garage sale. In my reading online this time I found out that these were more than mere decorations or emblems in that they were originally used to secure the special Brigham aluminum tenon into the shank of the pipe. Later they came to be used to denote the quality of each pipe. This also accounts for the use of the term “dot” instead of “series” among all of the Brigham collectors that I have met. From the website and web forums I found the following information regarding the “dot” grading system and created the comparison with the series numbers in the chart below. (This information is correct to the best of my knowledge though it is certainly open to correction and adjustment.)

There were originally 8 separate grades noted by the number and arrangement of the brass dots. These are arranged in the list starting with the lowest and ending with the highest grade. I have put the series number next to the dot information in the list below.  More reading led me to the next information I have edited and collated from the Brigham website. It is very helpful in terms of the stamping of the Brigham logo and patent information. It gave some direction for dating pipes to a certain era. Many of the pipes that I have in my collection that use the dots also have the Brigham patent number stamped on the shank, under or next to the name. It reads CAN PAT 372982. This number was stamped beside or under a cursive “Brigham” logo. This signature was thinner than the signature on the pipes found today. During the transition from this thin signature and patent stamping to the new logo adopted in the late 70s there were at least two variations of a cursive “Brigham” signature stamped into the pipes including two horizontally type-set fonts. I found out that the patent number appeared on pipes up to approximately 1980. After that date the new logo which is similar to the modern stamping though with the maple leaf, was used exclusively. All of my patent number pipes thus were pre-1980.