When I put this Barling away in my ‘Lazarus’ box, I thought that it might be from the Early Transition period, and therefore made from the last of that century old Algerian briar that Barling’s were famous for. I had not looked carefully at the nomenclature obscured beneath the grime. Noting that it was a Barling’s, I stored it away, looking forward to the opportunity to smoke from a piece of classic wood.

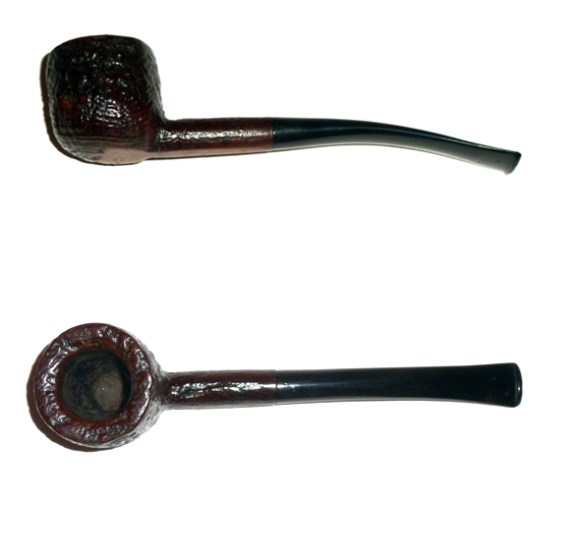

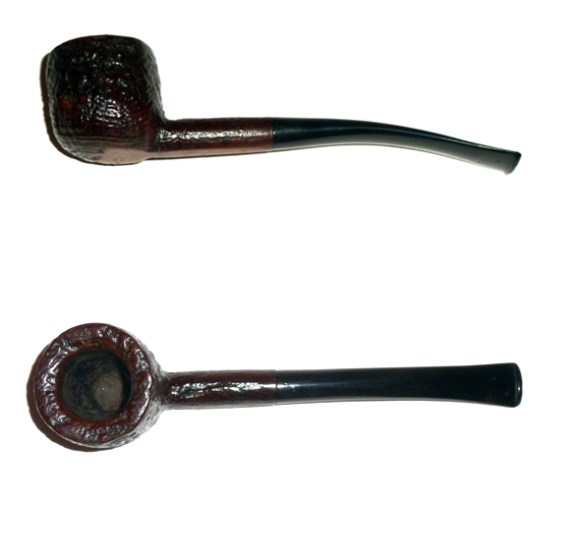

When I pulled it out and inspected the markings I was disappointed to find it had all the earmarks of a post transition period pipe. The Barling was in script, the model number had four digits, and T.V.F was stamped on the shank. Further, the bowl was not particularly well carved and there were several major fills – something you would never find on a Pre-transition family era pipe. Oh well. I decided to proceed with the refurb anyways.

I pulled a beautifully grained twin bore saddle bit Canadian from a drawer of miscellaneous pipes that I randomly smoke. It has no maker’s name, and is simply marked “France” 255. What a great smoker. Dry and sweet, it sang with the sample of Rincon De LA Pipe No. 1 sent to me compliments of 4noggins Tobacco. So, what’s in a name? You just never know…..

The pipe was in poor condition, having been snapped at the bowl junction where the shank was very thin.

The airway was also drilled off center, which may have contributed to the break.

Dirt and grime aside, the bowl chamber was not scorched or heavily caked. The stem had some tooth marks, but was more dirty than oxidized.

The bowl and shank were placed in my trusty container of 91% Isopropyl alcohol (99% is hard to fine in my neck of the woods) and left to soak for several hours. Meanwhile, the stem went into a bath of Oxy-Clean for 30 minutes, mostly to loosen any residual tars in the airway. Once soaked, pulling several bristle cleaners through the airway was all that was needed to clean out the gunk. After wet scrubbing the exterior with synthetic 0000 wool and Oxy-Clean, the stem was set aside to dry.

Once the bowl was done soaking, I cleaned the small amount of cake from the bowl with my Senior reamer, dipping the bowl in the bath to rinse out the bits and pieces that came free. Next, the exterior surfaces were scrubbed with the synthetic 0000 wool, working wet with clean alcohol.

At this point, with the cleaning finished, the Barling was beginning to come back to life. I set the pipe aside for the evening to let everything dry thoroughly before moving on to the bonding phase.

I used my favorite epoxy, JB Kwik to bond the shank back to the bowl. I set the two parts on a clean work surface, aligned as closely as possible, before mixing the epoxy. I applied a thin layer to both surfaces. I pressed the shank and bowl together, taking care to align the fracture, and let as much excess as possible squeeze out to minimize the joint. Hand pressure for three minutes is all that is needed for the initial bond. I then set the bowl down and let it rest for another 7 minutes (approximate). Under ideal temperature, humidity and proportioning, JB Kwik reaches a rubbery stage after 10 minutes. At this point, I removed the excess epoxy that squeezed from the joint with the tip of a utility knife blade. It peels off like a rubber gasket if you catch it at the right point as it cures. I then used the bit from my Senor reamer to carefully remove any excess epoxy that may have gotten into the airway. Care must be taken to work slowly and with very little pressure, as any leverage against the shank my cause the newly bonded joint to fail. Once the excess epoxy has been removed, I let the stummel cure for at least 6 hours.

With the pipe joined and epoxy cured, it was time to take the bowl and stem to the buffer for an initial polishing with red rouge. After cleaning any residual compound off with alcohol, the bowl was ready for stain. The stem needed some sanding to clean up the faint scouring from the synthetic 0000 wool. The Barling Cross logo was a faint memory, so conserving it was not a concern. 2×2 flex micro-mesh pads, 1500 through 4000, did the trick.

After two wash coats of Feibing’s Medium Brown aniline dye, and spot staining the two rather large fills (sorry, the photos were not usable), I wiped the bowl down vigorously with a micro-fiber cloth and set the stain with a table-top lighter. The micro-fiber cloth works wonders in evening out the coats of dye. Uneven coating or overlap marks blend beautifully when wiped down just after the dye dulls completely.

With the stain applied, the fills touched up, and the stem sanded, all that was left was a gentle once-over with white diamond, followed by three coats of carnauba wax on the bowl. The stem received a white diamond buff, followed by two coats of Briar Works Stem Wax and Sealer. I prefer to protect the stem this way, as my saliva tends to react with straight carnauba, leaving an unsightly white stain.

I’ll save the repair of the tooth dents on the stem for a future essay…..

It may be inferior, when compared to the legendary family era Barlings, but it was still fun to resurrect a pipe that could be half a century old. Sandblasted or rusticated pipes are much easier to repair in this manner, as the rough texture tends to hide the repair. The fracture is only evident on the smooth portion of the stem where the nomenclature resides.

Thanks for looking.

-Gan